The Atlantic

Since 1857, The Atlantic has been challenging assumptions and pursuing truth.

Don't post archive.is links or full text of articles, you will receive a temp ban.

On a bookshelf near my desk, I still have the souvenir United States flag that I received during my naturalization ceremony, in 1994. I remember a tenderhearted judge got emotional as the room full of immigrants swore the Oath of Allegiance and that, afterward, my family took me to Burgerville to celebrate. The next morning, my teacher asked me to explain to my classmates—all natural-born Americans—how I felt about becoming a citizen at age 13.

One girl had a question: “So Chris can never be president?”

I wasn’t worried about becoming president—I just wanted to get to the computer lab, where we were free to slaughter squirrels in The Oregon Trail. But her question revealed that even kids know there are two kinds of citizens: the ones who are born here, and the ones like me. The distinction is written into the Constitution, a one-line fissure that Donald Trump used to crack open the country: “Now we have to look at it,” Trump said, after compelling Barack Obama to release his birth certificate in 2011. “Is it real? Is it proper?”

Nearly 25 million naturalized citizens live in the U.S., and we are accustomed to extra scrutiny. I expect supplemental questions on medical forms, close inspection at border crossings, and bureaucratic requests to see my naturalization certificate. But I had never doubted that my U.S. citizenship was permanent, and that I was guaranteed the same rights of speech, assembly, and due process as natural-born Americans. Now I’m not so sure.

Last month, the Department of Justice released a civil-enforcement memo listing the denaturalization of U.S. citizens as a top-five priority and pledging to “maximally pursue” all viable cases, including people who are “a potential danger to national security” and, more vague, anyone “sufficiently important to pursue.” President Trump has suggested that targets could include citizens whom he views as his political enemies, such as Zohran Mamdani, the New York City mayoral candidate who was born in Uganda and naturalized in 2018: “A lot of people are saying he’s here illegally,” Trump said. “We’re going to look at everything.”

[Read: Why civics is about more than citizenship]

Looking at everything can be unnerving for naturalized citizens. Our document trails can span decades and continents. Thankfully, I was naturalized as a child, before I had much background to check, before the internet, before online surveillance. I was born in Brazil, in 1981, during the twilight of its military dictatorship, and transplanted to the United States as a baby through a byzantine international-adoption process. My birth mother had no way of knowing for sure what awaited me, but she understood that her child would have a better chance in the “land of the free.”

I don’t consider myself “a potential danger to national security” or “sufficiently important to pursue,” but I also don’t believe that American security is threatened by international students, campus protesters, or undocumented people selling hot dogs at Home Depot. I’m a professor who writes critically about American power, I believe in civil disobedience, and I support my students when they exercise their freedom of conscience.

Because I was naturalized as a child, I didn’t have to take the famous civics test—I was still learning that stuff in school. I just rolled my fingertips in wet ink and held still for a three-quarter-profile photograph that revealed my nose shape, ear placement, jawline, and forehead contour. My parents sat beside me for an interview with an immigration officer who asked me my name, where I lived, and who took care of me.

But these days, I wonder a lot about that civics test. It consists of 10 questions, selected from a list of 100, on the principles of democracy, our system of government, our rights and responsibilities, and milestones in American history. The test is oral; an official asks questions in deliberately slow, even tones, checking the responses against a list of sanctioned answers. Applicants need to get only six answers correct in order to pass. Democracy is messy, but this test is supposed to be easy.

However, so much has changed in the past few years that I’m not sure how a prospective citizen would answer those questions today. Are the correct answers to the test still true of the United States?

What does the Constitution do? The Constitution protects the basic rights of Americans.

One of the Constitution’s bedrock principles can be traced back to a revision that Thomas Jefferson made to an early draft of the Declaration of Independence, replacing “our fellow subjects” with “our fellow citizens.”

As with constitutional theories of executive power, theories of citizenship are subject to interpretation. Chief Justice Earl Warren distilled the concept as “the right to have rights.” His Court deemed the revocation of citizenship cruel and unusual, tantamount to banishment, “a form of punishment more primitive than torture.”

By testing the constitutional rights of citizenship on two fronts—attempting to denaturalize Americans and to strip away birthright citizenship—Trump is claiming the power of a king to banish his subjects. In the United States, citizens choose the president. The president does not choose citizens

What is the **“**rule of law”? Nobody is above the law.

Except, perhaps, the president, who is immune from criminal prosecution for official acts performed while in office. Trump is distorting that principle by directing the Department of Justice, the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and ICE to enforce his own vision of the law without regard for constitutional norms.

Civil law is more malleable than criminal law, with fewer assurances of due process and a lower burden of proof. ICE raids rely on kinetic force to fill detention cells. Denaturalization cases can rely on stealthy legal proceedings. In 2018, the Trump administration stripped a man of his citizenship. He was married to a U.S. citizen and had been naturalized for 12 years. The administration accused him of fraudulently using an alias to apply for his papers after having been ordered to leave the country. In an article for the American Bar Association, two legal scholars argued that this was more likely the result of a bureaucratic mix-up. Whatever the truth of the matter, the summons was served to an old address, and the man lost his citizenship without ever having had the chance to defend himself in a hearing.

[Read: The fragility of American citizenship]

The DOJ is signaling an aggressive pursuit of denaturalization that could lead to more cases like these. In the most extreme scenarios, Americans could be banished to a country where they have no connection or even passing familiarity with the language or culture.

What stops one branch of government from becoming too powerful? Checks and balances.

Denaturalization efforts may fail in federal court, but the Trump administration has a habit of acting first and answering to judges later. When courts do intervene, a decision can take weeks or months, and the Supreme Court recently ruled that federal judges lack the authority to order nationwide injunctions while they review an individual case. FBI and ICE investigations, however, can be opened quickly and have been accelerated by new surveillance technologies.

How far might a Trump administration unbound by the courts go? Few people foresaw late-night deportation flights to El Salvador, the deployment of U.S. Marines to Los Angeles, a U.S. senator thrown to the ground and handcuffed by FBI agents for speaking out during a Department of Homeland Security press conference. To many Americans who have roots in countries with an authoritarian government, these events don’t seem so alien.

What is one right or freedom from the First Amendment? Speech.

And all the rights that flow from it: Assembly. Religion. Press. Petitioning the government.

During the McCarthy era, the Department of Justice targeted alleged anarchists and Communists for denaturalization, scrutinizing the years well before and after they had arrived in the U.S. for evidence of any lack of “moral character,” which could include gambling, drunkenness, or affiliation with labor unions. From 1907 to 1967, more than 22,000 Americans were denaturalized.

Even if only a handful of people are stripped of their citizenship in the coming years, it would be enough to chill the speech of countless naturalized citizens, many of whom are already cautious about exercising their First Amendment rights. The mere prospect of a lengthy, costly, traumatic legal proceeding is enough to induce silence.

What are two ways that Americans can participate in their democracy? Help with a campaign. Publicly support or oppose an issue or policy.

If, apparently, it’s the “proper” campaign, issue, or policy.

What movement tried to end racial discrimination? The civil-rights movement.

The question of who has the right to have rights is as old as our republic. Since the Constitutional Convention, white Americans have fiercely debated the citizenship rights of Indigenous Americans, Black people, and women. The Fourteenth Amendment, which established birthright citizenship, and equal protection under the law for Black Americans, was the most transformative outcome of the Civil War. Until 1940, an American woman who married a foreign-born man could be stripped of her citizenship. Only through civil unrest and civil disobedience did the long arc of the moral universe bend toward justice.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act opened the door for the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which ended the national-origin quotas that had limited immigration from Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. The act “corrects a cruel and enduring wrong in the conduct of the American Nation,” President Lyndon B. Johnson said as he signed the immigration bill at the foot of the Statue of Liberty. The possibility of multiracial democracy emerged from the civil-rights movement and the laws that followed. Turning back the clock on race and citizenship, and stoking fears about the blood of America, is a return to injustice and cruelty.

What is one promise you make when you become a United States citizen? To support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic.

Now Americans like me have to wonder if we can hold true to that promise, or whether speaking up for the Constitution could jeopardize our citizenship.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

Late last month, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy released a document detailing its vision for scientific integrity. Its nine tenets, first laid out in President Donald Trump’s executive order for “Restoring Gold Standard Science,” seem anodyne enough: They include calls for federal and federally supported science to be reproducible and transparent, communicative of error and uncertainty, and subject to unbiased peer review. Some of the tenets might be difficult to apply in practice—one can’t simply reproduce the results of studies on the health effects of climate disasters, for example, and funding is rarely available to replicate expensive studies. But these unremarkable principles hide a dramatic shift in the relationship between science and government.

Trump’s executive order promises to ensure that “federal decisions are informed by the most credible, reliable, and impartial scientific evidence available.” In practice, however, it gives political appointees—most of whom are not scientists—the authority to define scientific integrity and then decide which evidence counts and how it should be interpreted. The president has said that these measures are necessary to restore trust in the nation’s scientific enterprise—which has indeed eroded since the last time he was in office. But these changes will likely only undermine trust further. Political officials no longer need to rigorously disprove existing findings; they can cast doubt on inconvenient evidence, or demand unattainable levels of certainty, to make those conclusions appear unsettled or unreliable.

In this way, the executive order opens the door to reshaping science to fit policy goals rather than allowing policy to be guided by the best available evidence. Its tactics echo the “doubt science” pioneered by the tobacco industry, which enabled cigarette manufacturers to market a deadly product for decades. But the tobacco industry could only have dreamed of having the immense power of the federal government. Applied to government, these tactics are ushering this country into a new era of doubt in science and enabling political appointees to block any regulatory action they want to, whether it’s approving a new drug or limiting harmful pollutants.

Historically, political appointees generally—though not always—deferred to career government scientists when assessing and reporting on the scientific evidence underlying policy decisions. But during Trump’s first term, these norms began to break down, and political officials asserted far greater control over all facets of science-intensive policy making, particularly in contentious areas such as climate science. In response, the Biden administration invested considerable effort in restoring scientific integrity and independence, building new procedures and frameworks to bolster the role of career scientists in federal decision making.

Trump’s new executive order not only rescinds these Joe Biden–era reforms but also reconceptualizes the meaning of scientific integrity. Under the Biden-era framework, for example, the definition of scientific integrity focused on “professional practices, ethical behavior, and the principles of honesty and objectivity when conducting, managing, using the results of, and communicating about science and scientific activities.” The framework also emphasized transparency, and political appointees and career staff were both required to uphold these scientific standards. Now the Trump administration has scrapped that process, and appointees enjoy full control over what scientific integrity means and how agencies review and synthesize scientific literature necessary to support and shape policy decisions.

Although not perfect, the Biden framework also included a way for scientists to appeal decisions by their supervisors. By contrast, Trump’s executive order creates a mechanism by which career scientists who publicly dissent from the pronouncements of political appointees can be charged with “scientific misconduct” and be subject to disciplinary action. The order says such misconduct does not include differences of opinion, but gives political appointees the power to determine what counts, while providing employees no route for appeal. This dovetails with other proposals by the administration to make it easier to fire career employees who express inconvenient scientific judgments.

When reached for comment, White House spokesperson Kush Desai argued that “public perception of scientific integrity completely eroded during the COVID era, when Democrats and the Biden administration consistently invoked an unimpeachable ‘the science’ to justify and shut down any reasonable questioning of unscientific lockdowns, school shutdowns, and various intrusive mandates” and that the administration is now “rectifying the American people’s complete lack of trust of this politicized scientific establishment.”

But the reality is that, armed with this new executive order, officials can now fill the administrative record with caveats, uncertainties, and methodological limitations—regardless of their relevance or significance, and often regardless of whether they could ever realistically be resolved. This strategy is especially powerful against standards enacted under a statute that takes a precautionary approach in the face of limited scientific evidence.

Some of our most important protections have been implemented while acknowledging scientific uncertainty. In 1978, although industry groups objected that uncertainty was still too high to justify regulations, several agencies banned the use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) as propellants in aerosol spray cans, based on modeling that predicted CFCs were destroying the ozone layer. The results of the modeling were eventually confirmed, and the scientists who did the work were awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Elevating scientific uncertainty above other values gives political appointees a new tool to roll back public-health and environmental standards and to justify regulatory inaction. The result is a scientific record created less to inform sound decision making than to delay it—giving priority to what we don’t know over what we do. Certainly, probing weaknesses in scientific findings is central to the scientific enterprise, and good science should look squarely at ways in which accepted truths might be wrong. But manufacturing and magnifying doubt undercuts science’s ability to describe reality with precision and fealty, and undermines legislation that directs agencies to err on the side of protecting health and the environment. In this way, the Trump administration can effectively violate statutory requirements by stealth, undermining Congress’s mandate for precaution by manipulating the scientific record to appear more uncertain than scientists believe it is.

An example helps bring these dynamics into sharper focus. In recent years, numerous studies have linked PFAS compounds—known as “forever chemicals” because they break down extremely slowly, if at all, in the environment and in human bodies—to a range of health problems, including immunologic and reproductive effects; developmental effects or delays in children, including low birth weight, accelerated puberty, and behavioral changes; and increased risk of prostate, kidney, and testicular cancers.

Yet despite promises from EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin to better protect the public from PFAS compounds, efforts to weaken current protections are already under way. The president has installed in a key position at the EPA a former chemical-industry executive who, in the first Trump administration, helped make regulating PFAS compounds more difficult. After industry objected to rules issued by the Biden administration, Trump’s EPA announced that it is delaying enforcement of drinking-water standards for two of the PFAS forever chemicals until 2031 and rescinding the standards for four others. But Zeldin faces a major hurdle in accomplishing this feat: The existing PFAS standards are backed by the best currently available scientific evidence linking these specific chemicals to a range of adverse health effects.

Here, the executive order provides exactly the tools needed to rewrite the scientific basis for such a decision. First, political officials can redefine what counts as valid science by establishing their own version of the “gold standard.” Appointees can instruct government scientists to comb through the revised body of evidence and highlight every disagreement or limitation—regardless of its relevance or scientific weight. They can cherry-pick the data, giving greater weight to studies that support a favored result. Emphasizing uncertainty biases the government toward inaction: The evidence no longer justifies regulating these exposures.

This “doubt science” strategy is further enabled by industry’s long-standing refusal to test many of its own PFAS compounds—of which there are more than 12,000, only a fraction of which have been tested—creating large evidence gaps. The administration can claim that regulation is premature until more “gold standard” research is conducted. But who will conduct that research? Industry has little incentive to investigate the risks of its own products, and the Trump administration has shown no interest in requiring it to do so. Furthermore, the government controls the flow of federal research funding and can restrict public science at its source. In fact, the EPA under Trump has already canceled millions of dollars in PFAS research, asserting that the work is “no longer consistent with EPA funding priorities.”

In a broader context, the “gold standard” executive order is just one part of the administration’s larger effort to weaken the nation’s scientific infrastructure. Rather than restore “the scientific enterprise and institutions that create and apply scientific knowledge in service of the public good,” as the executive order promises, Elon Musk and his DOGE crew fired hundreds, if not thousands, of career scientists and abruptly terminated billions of dollars of ongoing research. To ensure that federal research support remains low, Trump’s recently proposed budget slashes the research budgets of virtually every government research agency, including the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the EPA.

Following the hollowing-out of the nation’s scientific infrastructure through deep funding cuts and the firing of federal scientists, the executive order is an attempt to rewrite the rules of how our expert bureaucracy operates. It marks a fundamental shift: The already weakened expert agencies will no longer be tasked with producing scientific findings that are reliable by professional standards and insulated from political pressure. Instead, political officials get to intervene at any point to elevate studies that support their agenda and, when necessary, are able to direct agency staff—under threat of insubordination—to scour the record for every conceivable uncertainty or point of disagreement. The result is a system in which science, rather than informing policy, is shaped to serve it.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

Welcome back to The Daily’s Sunday culture edition.

Announcements of yet another book-to-film adaptation are usually met with groans by fans of the source material. But sometimes a new movie can be a chance to lift the best elements of a story. We asked The Atlantic’s writers and editors: What’s a film adaptation that’s better than the book?

Jurassic Park (streaming on Peacock)

I am not saying that the Michael Crichton novel Jurassic Parkisn’t great, because it is. The folly of man, the chaos of progress, the forking around, the finding out, the dinosaurs—God, the dinosaurs. But in 1993, Steven Spielberg took this promising genetic code, selected the fittest elements, spliced them with Hitchcock, and adapted them to the cool dark of the multiplex. The result is not just a great movie. It is a perfect movie.

The story is tighter; the characters are given foils, mirrors, and stronger arcs. On the page, Dr. Alan Grant is a widower and the paleobotanist Ellie Sattler his student; Dr. Ian Malcolm, chaos mathematician, is a balding know-it-all. On the screen, our dear Dr. Sattler feasts on Dr. Grant’s restrained, tonic masculinity and Dr. Malcolm’s camp erotic magnetism (as do we). The dialogue is punchier too. “You’re alive when they start to eat you,” “Woman inherits the Earth,” “Clever girl,” “Hold on to your butts”—none of that poetry appears in the paperback.

Spielberg and his crew used CGI techniques to make the inhabitants of Isla Nublar come to life, but the real magic came from practical effects, including a 9,000-pound, bus-size animatronic T. rex. This ferocious predator deserves to live on-screen, chomping on velociraptors and snatching a lawyer off of the toilet. Thirty years later, I am still not sure man deserves to watch.

— Annie Lowrey, staff writer

***

The Talented Mr. Ripley (streaming on Paramount+ and the Criterion Channel)

Patricia Highsmith wrote eminently filmable novels, none more so than her oft-adapted The Talented Mr. Ripley. The 1999 movie is the most famous and successful take, transforming the source material into a faster-paced and more suspenseful version of the story. The novel’s crime-to-punishment ratio is Dostoyevskian; for each misdeed Tom Ripley commits, he spends twice as long regretting it or worrying that he’ll get caught. Anthony Minghella’s adaptation diverges from this claustrophobic narration and limits viewers’ access into Ripley’s mind, making his deceitful and violent actions all the more unexpected.

The final scenes contain the largest plot deviation—a shocking twist that manages to both show Ripley at his worst and invite sympathy for him. The film also clarifies his tortured sexuality, an element of his character that remains more ambiguous in the novel. What Highsmith hints at, Minghella more boldly asks: When someone is already ostracized, even criminalized, by society, what’s to stop him from taking the leap into actual depravity?

— Dan Goff, copy editor

***

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (available to rent on YouTube and Prime Video)

I’m going to make some people mad, but the 2011 adaptation of John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is even better than the superb novel. It’s a rare instance of a spy movie that transcends genre and stands on its own. Gary Oldman’s portrayal of the intelligence officer George Smiley is one of the great performances of the 21st century—and it probably paved the way for Oldman to eventually play Jackson Lamb in the addictive Slow Horses series, also an adaptation. The treatment of the field agent Ricki Tarr (played by Tom Hardy) is both more intense and to the point than in the novel. The scenery—the shots of Budapest alone—brings le Carré’s writing to life in a way that few adaptations ever do. And the film has easily one of the most gripping, poignant, and creative final scenes I’ve ever seen. (Julio Iglesias’s rendition of “La Mer” is on my dinner-party playlist. If you know, you know.)

— Shane Harris, staff writer

***

The Devil Wears Prada (streaming on Disney+)

At first glance, the 2006 film The Devil Wears Prada seems to make only cosmetic changes to Lauren Weisberger’s fizzy novel about a young woman trying to break into New York’s publishing industry. In the movie, the protagonist, Andy, is a graduate of Northwestern, instead of Brown. Her boyfriend is a chef, not a teacher. And Miranda Priestly, the imposing editor of a fashion magazine—a thinly veiled version of Anna Wintour—who hires Andy as an assistant, isn’t always seen wearing a white Hermès scarf.

But the movie’s sharp screenplay by Aline Brosh McKenna elevated the material past its breezy, chick-lit-y origins. Anchored by a top-notch cast (Anne Hathaway as Andy, Meryl Streep as Miranda, and a breakout Emily Blunt as Andy’s workplace rival), the film is the rare rom-com focused more on professional relationships than romantic ones: between mentors and mentees, bosses and employees, colleagues and competitors. Even amid its glossy setting, The Devil Wears Prada captured the reality of work, showing how finding career fulfillment can be a blessing and a curse. For me, the film is a modern classic, endlessly rewatchable for its insights—and, of course, its fashion. I certainly have never looked at the color cerulean the same way again.

— Shirley Li, staff writer

***

The Social Network (available to rent on Prime Video and YouTube)

Did Mark Zuckerberg’s girlfriend really break up with him by calling him an asshole in the middle of a date? Did he actually spend the moments after a disastrous legal deposition refreshing a Facebook page, again and again, to see if she’d accepted his friend request? Well, probably not—Erica Albright, Rooney Mara’s character in David Fincher’s film The Social Network, is admittedly fictional. But her opening scene establishes Fincher’s version of Mark Zuckerberg as a smug, patronizing jerk who can’t imagine other people’s feelings being as important as his own, and sets the movie off at a furious, thrilling pace that doesn’t slow until the very end, when Mark has alienated everyone who once cared about him.

The Social Network is a biopic that doesn’t hold itself to facts, to its absolute advantage. Ironically, this approach elevates the nonfiction book it’s based on, Ben Mezrich’s The Accidental Billionaires, which was written without even an interview with Zuckerberg and panned as shoddily reported. (In a New York Times review, Janet Maslin wrote that Mezrich’s “working method” seemed to be “wild guessing.”) The truth doesn’t matter as much as telling a good story—as long as you keep control of the narrative, which Fincher’s Mark struggles to do.

— Emma Sarappo, senior associate editor

***

Clear and Present Danger (streaming on MGM+)

Clear and Present Danger the book is the size, shape, and weight of a brick; Phillip Noyce’s bureaucratic thriller slims Tom Clancy’s nearly 1,000 pages into a svelte 141 minutes (though movies could always be shorter). The action takes place on the sea, in the jungle, at a drug lord’s mansion, and in the streets of Bogotá—the latter setting the scene for an ambush sequence so memorable that the Jack Ryan series restaged it. But the film is most gripping in hallways and offices, culminating in Henry Czerny and Harrison Ford brandishing dueling memos at each other like light sabers. (“You broke the law!”) And although the character of Jack Ryan can sometimes blur into a cipher in Clancy’s novels, Ford embodies him with a Beltway Dad gravitas—never more so than when he announces to the lawbreaking president of the United States, “It is my duty to report this matter to the Senate Oversight Committee!” Such a Boy Scout.

— Evan McMurry, senior editor

Here are three Sunday reads from The Atlantic:

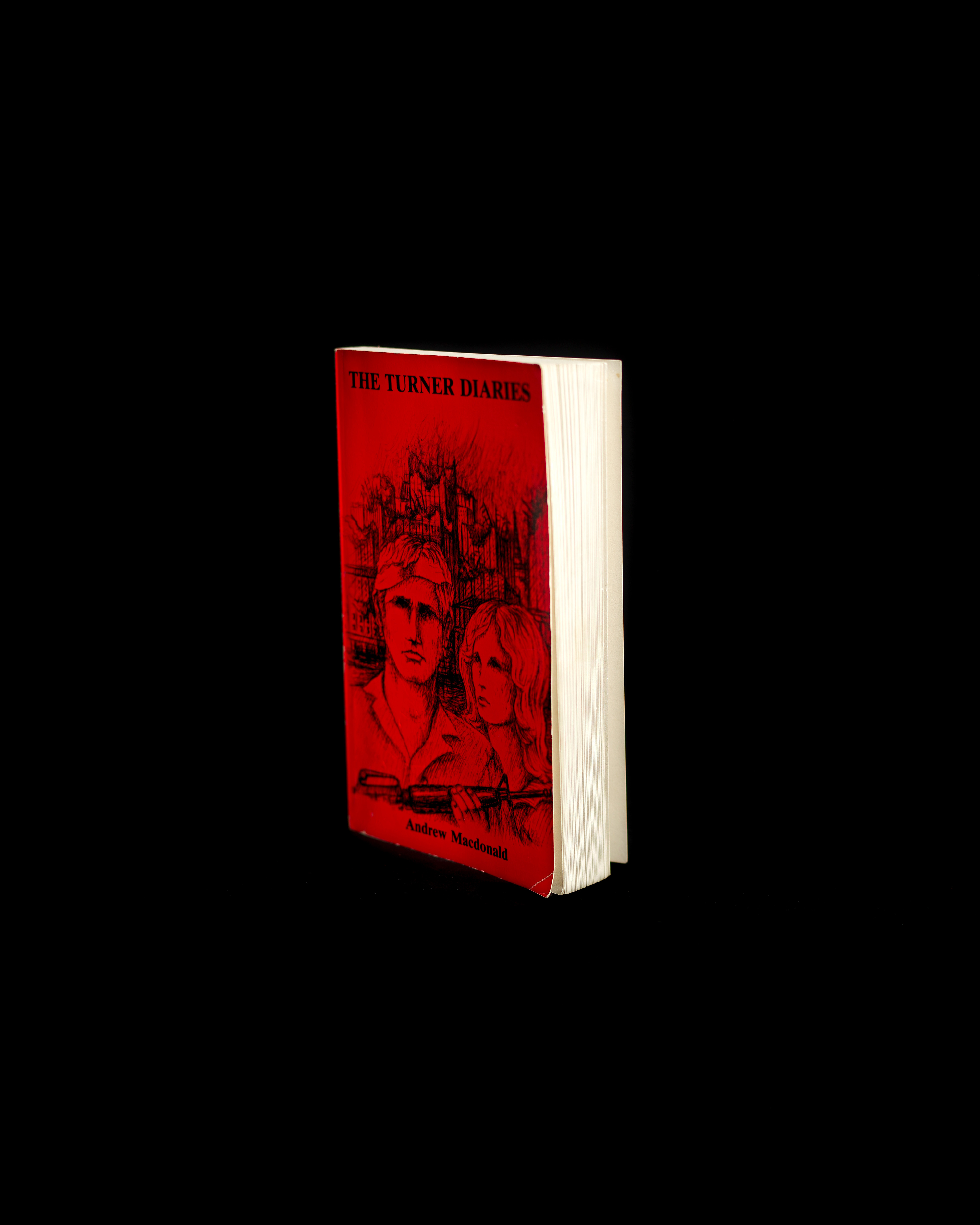

What to do with the most dangerous book in AmericaAndrea Gibson refused to “battle” cancer.How to be more charismatic, but not too much more

The Week Ahead

The**Fantastic Four: First Steps, a Marvel movie about a group of superheroes who face off with Galactus and Silver Surfer (in theaters Friday)Veronica Electronica, a new remix album by Madonna (out Friday)Girl, 1983, a novel by Linn Ullmann about the power of forgetting (out Tuesday)

Essay

Pixar

Pixar

What Pixar Should Learn From Its Elio Disaster

By David Sims

Early last year, Pixar appeared to be on the brink of an existential crisis. The coronavirus pandemic had thrown the business of kids’ movies into particular turmoil: Many theatrical features were pushed to streaming, and their success on those platforms left studios wondering whether the appeal of at-home convenience would be impossible to reverse … Discussing the studio’s next film, Inside Out 2, the company’s chief creative officer, Pete Docter, acknowledged the concerns: “If this doesn’t do well at the theater, I think it just means we’re going to have to think even more radically about how we run our business.”

He had nothing to worry about: Inside Out 2 was a financial sensation—by far the biggest hit of 2024. Yet here we are, one year later, and the question is bubbling back up: Is Pixar cooked?

More in Culture

Romance on-screen has never been colder. Maybe that’s just truthful.Sexting with GeminiDear James: “My ex and I were horrible to each other.”Let your kid climb that tree.The reality show that captures Gen Z dating

Catch Up on The Atlantic

The Court’s liberals are trying to tell Americans something.The Trump administration is about to incinerate 500 tons of emergency food.Is Colbert’s ouster really just a “financial decision”?

Photo Album

A recortador performs with a bull in the Plaza de Toros bullring during a festival in Pamplona, Spain. (Ander Gillenea / AFP / Getty)

A recortador performs with a bull in the Plaza de Toros bullring during a festival in Pamplona, Spain. (Ander Gillenea / AFP / Getty)

Take a look at these photos of the week, which show a trust jump in Iraq, a homemade-submarine debut in China, and more.

Explore all of our newsletters.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic*.*

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

Can the city of New York sell groceries more cheaply than the private sector? The mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani thinks so. He wants to start five city-owned stores that will be “focused on keeping prices low” rather than making a profit—what he calls a “public option” for groceries. His proposal calls for opening stores on city land so that they can forgo paying rent or property taxes.

Skeptics have focused on economic obstacles to the plan. Grocers have industry expertise that New York City lacks; they benefit from scale; and they run on thin profit margins, estimated at just 1 to 3 percent, leaving little room for additional savings. Less discussed, though no less formidable, is a political obstacle for Mamdani: The self-described democratic socialist’s promise to lower grocery prices and, more generally, “lower the cost of living for working class New Yorkers” will be undermined by other policies that he or his coalition favors that would raise costs. No one should trust that “there’s far more efficiency to be had in our public sector,” as he says of his grocery-store proposal, until he explains how he would resolve those conflicts.

Mamdani’s desire to reduce grocery prices for New Yorkers is undercut most glaringly by the labor policies that he champions. Labor is the largest fixed cost for grocery stores. Right now grocery-store chains with lots of New York locations, such as Stop & Shop and Key Food, advertise entry-level positions at or near the city’s minimum wage of $16.50 an hour. Mamdani has proposed to almost double the minimum wage in New York City to $30 an hour by 2030; after that, additional increases would be indexed to inflation or productivity growth, whichever is higher. Perhaps existing grocery workers are underpaid; perhaps workers at city-run stores should make $30 an hour too. Yet a wage increase would all but guarantee more expensive groceries. Voters deserve to know whether he’ll prioritize cheaper groceries or better-paid workers. (I wrote to Mamdani’s campaign about this trade-off, and others noted below, but got no reply.)

[Read: New York is hungry for a big grocery experiment]

In the New York State assembly, Mamdani has co-sponsored legislation to expand family-leave benefits so that they extend to workers who have an abortion, a miscarriage, or a stillbirth. The official platform of the Democratic Socialists of America, which endorsed Mamdani, calls for “a four-day, 32-hour work week with no reduction in wages or benefits” for all workers. Unions, another source of Mamdani support, regularly lobby for more generous worker benefits. Extending such benefits to grocery-store employees would raise costs that, again, usually get passed on to consumers. Perhaps Mamdani intends to break with his own past stances and members of his coalition, in keeping with his goal of focusing on low prices. But if that’s a path that he intends to take, he hasn’t said so.

City-run grocery stores would purchase massive amounts of food and other consumer goods from wholesalers. New York City already prioritizes goals other than cost-cutting when it procures food for municipal purposes; it signed a pledge in 2021 to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions associated with food that it serves, and Mayor Eric Adams signed executive orders in 2022 that committed the city to considering “local economies, environmental sustainability, valued workforce, animal welfare, and nutrition” in its food procurement. Such initiatives inevitably raise costs.

Mamdani could favor exempting city-run groceries from these kinds of obligations. But would he? Batul Hassan, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America steering committee and a supporter of Mamdani, co-authored an article arguing that city-run stores should procure food from vendors that prioritize a whole host of goods: “worker dignity and safety, animal welfare, community economic benefit and local sourcing, impacts to the environment, and health and nutrition, including emphasizing culturally appropriate, well-balanced and plant-based diets,” in addition to “suppliers from marginalized backgrounds and non-corporate supply chains, including small, diversified family farms, immigrants and people of color, new and emerging consumer brands, and farmer and employee owned cooperatives.” If one milk brand is cheaper but has much bigger environmental externalities or is owned by a large corporation, will a city-run store carry it or a pricier but greener, smaller brand?

Mamdani has said in the past that he supports the BDS (boycott, divestment, sanctions) movement, which advocates for boycotting products from Israel. That probably wouldn’t raise costs much by itself. And Mamdani told Politico in April that BDS wouldn’t be his focus as mayor. But a general practice of avoiding goods because of their national origin, or a labor dispute between a supplier and its workers, or any number of other controversies, could raise costs. When asked about BDS in the Politico interview, Mamdani also said, “We have to use every tool that is at people’s disposal to ensure that equality is not simply a hope, but a reality.” Would Mamdani prioritize low prices in all cases or sometimes prioritize the power of boycotts or related pressure tactics to effect social change? Again, he should clarify how he would resolve such trade-offs.

Finally, shoplifting has surged in New York in recent years. Many privately owned grocery stores hire security guards, use video surveillance, call police on shoplifters, and urge that shoplifters be prosecuted. Democratic socialists generally favor less policing and surveilling. If the security strategy that’s best for the bottom line comes into conflict with progressive values, what will Mamdani prioritize?

This problem isn’t unique to Mamdani. Officials in progressive jurisdictions across the country have added to the cost of public-sector initiatives by imposing what The New York Times’s Ezra Klein has characterized as an “avalanche of well-meaning rules and standards.” For example, many progressives say they want to fund affordable housing, but rather than focus on minimizing costs per unit to house as many people as possible, they mandate other goals, such as giving locals a lengthy process for comment, prioritizing bids from small or minority-owned businesses, requiring union labor, and instituting project reviews to meet the needs of people with disabilities. Each extra step relates to a real good. But once you add them up, affordability is no longer possible, and fewer people end up housed.

Policies that raise costs are not necessarily morally or practically inferior to policies that lower costs; low prices are one good among many. But if the whole point of city-owned grocery stores is to offer lower prices, Mamdani will likely need to jettison other goods that he and his supporters value, and be willing to withstand political pressure from allies. Voters deserve to know how Mamdani will resolve the conflicts that will inevitably arise. So far, he isn’t saying.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

This is an edition of The Wonder Reader, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a set of stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight. Sign up here to get it every Saturday morning.

A family vacation can seem like the solution to all of life’s tensions: You’ll spend time together, bond, and experience a new place. But travel isn’t a panacea. As Kim Brooks wrote last year about her own halting attempts at taking a successful trip with her kids: “Gradually, lounging among my own dashed hopes, I began to understand that no family vacation was going to change who I was.” Today’s newsletter explores how family trips have changed, and how to make the most of your time with loved ones without expecting too much.

On Family Vacations

On Failing the Family Vacation

By Kim Brooks

How I got dumped, went on a cruise, and embraced radical self-acceptance

The New Family Vacation

By Michael Waters

More and more Americans are traveling with multiple generations—and, perhaps, learning who their relatives really are.

Plan Ahead. Don’t Post.

By Arthur C. Brooks

And seven other rules for a happy vacation

Still Curious?

Summer vacation is moving indoors: Extreme heat is changing summer for kids as we know it.The rise and fall of the family-vacation road trip: The golden age of family road-tripping was a distinctly American phenomenon.

Other Diversions

How to be more charismatic, but not too much moreWhat becoming a parent really does to your happinessWeird, wonderful photos from the archives

P.S.

Courtesy of Ellen Walker

Courtesy of Ellen Walker

I recently asked readers to share a photo of something that sparks their sense of awe in the world. Ellen Walker, 69, shared this photo taken on Loch Linnhe in western Scotland in 2019. “We were visiting friends who live south of Glasgow and with whom we take annual biking trips,” Ellen writes. “It had rained much of the time we were exploring the west coast (as it will do in Scotland!) but I began to see the infinite varieties of grey as spectacularly beautiful. When the sun tried to peek through the clouds I snapped this photo and was so pleased to be able to capture the richness of the scene. It no longer seemed gloomy. I was in awe.”

I’ll continue to feature your responses in the coming weeks.

— Isabel

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

The early aughts were the worst possible kind of golden age. Tans were inescapable—on Britney Spears’s midriff, on the flexing biceps outside of Abercrombie & Fitch stores. The Jersey Shore ethos of “gym, tan, laundry” infamously encapsulated an era in which tanning salons were after-school hangouts, and tanning stencils in the shape of the Playboy bunny were considered stylish. Self-tanning lotions, spray tans, and bronzers proliferated, but people still sought the real thing.

By the end of the decade, tanning’s appeal had faded. Americans became more aware of the health risks, and the recession shrank their indoor-tanning budgets. But now America glows once again. The president and many of his acolytes verge on orange, and parties thrown by the MAGA youth are blurs of bronze. Celebrity tans are approaching early-aughts amber, and if dermatologists’ observations and social media are any indication, teens are flocking to the beach in pursuit of scorching burns.

Tanning is back. Only this time, it’s not just about looking good—it’s about embracing an entire ideology.

Another apparent fan of tanning is Robert F. Kennedy Jr., America’s perpetually bronzed health secretary, who was spotted visiting a tanning salon last month. What tanning methods he might employ are unknown, but the secretary’s glow is undeniable. (The Department of Health and Human Services didn’t respond to a request for comment about the administration’s views on tanning or Kennedy’s own habits.)

On its face, the idea that any health secretary would embrace tanning is odd. The Obama administration levied an excise tax on tanning beds and squashed ads that marketed tanning as healthy. The Biden administration, by contrast, made sunscreen use and reducing sun exposure%20support%20patients%20and%20caregivers.) central to its Cancer Moonshot plan. The stated mission of Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again movement is to end chronic diseases, such as cancer, by addressing their root causes. Yet the Trump administration’s MAHA report, released in May, doesn’t once mention skin cancer, which is the most common type as well as the most easily preventable. It mentions the sun only to note its connection with circadian rhythm: “Morning sun synchronizes the body’s internal clock, boosting mood and metabolism.”

In fact, there’s good reason to suspect that Kennedy and others in his orbit will encourage Americans to get even more sun. Last October, in a post on X, Kennedy warned that the FDA’s “aggressive suppression” of sunlight, among other supposedly healthy interventions, was “about to end.” Casey Means, a doctor and wellness influencer whom President Donald Trump has nominated for surgeon general, is also a sun apologist. In her best-selling book, Good Energy (which she published with her brother, Calley Means, an adviser to Kennedy), she argues that America’s many ailments are symptoms of a “larger spiritual crisis” caused by separation from basic biological needs, including sunlight. “Shockingly, we rarely ever hear about how getting direct sunlight into our eyes at the right times is profoundly important for metabolic and overall health,” she writes. An earlier version of Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill tried to repeal the excise tax on tanning beds. (The provision was cut in the final version.)

The alternative-health circles that tend to attract the MAHA crowd are likewise skeptical of sun avoidance. “They don’t want you to know this. But your body was made for the sun,” says a “somatic energy healer” with 600,000 followers who promotes staring directly into the sun to boost mood and regulate the body’s circadian rhythm. (Please, don’t do this.) On social media, some influencers tout the sun’s supposedly uncelebrated power to increase serotonin and vitamin D, the latter of which some erroneously view as a cure-all. Some promote tanning-bed use as a way to relieve stress; others, such as the alternative-health influencer Carnivore Aurelius, promote genital tanning to boost testosterone. Another popular conspiracy theory is that sunscreen causes cancer and is promoted by Big Pharma to keep people sick; a 2024 survey found that 14 percent of young adults think using sunscreen every day is worse for the skin than going without it.

These claims range from partly true to patently false. The sun can boost serotonin and vitamin D, plus regulate circadian rhythm—but these facts have long been a part of public-health messaging, and there’s no evidence that these benefits require eschewing sunscreen or staring directly at our star. Tanning beds emit little of the UVB necessary to produce vitamin D. Some research suggests that the chemicals in sunscreen can enter the bloodstream, but only if it’s applied to most of the body multiple times a day; plus, the effects of those chemicals in the body haven’t been established to be harmful, whereas skin cancer has. And, if I really have to say it: No solid research supports testicle tanning. Nor does any of this negate the sun’s less salutary effects: premature aging, eye damage, and greatly increased risk of skin cancer, including potentially fatal melanomas.

The specific questions raised in alternative-health spaces matter less than the conspiracist spirit in which they are asked: What haven’t the American people been told about the sun? What lies have we been fed? Their inherent skepticism aligns with Kennedy’s reflexive mistrust of the health establishment. In the MAHA world, milk is better when it’s raw, beef fat is healthier than processed oils, and the immune system is strongest when unvaccinated. This philosophy, however flawed, appeals to the many Americans who feel that they’ve been failed by the institutions meant to protect them. It offers the possibility that regaining one’s health can be as simple as rejecting science and returning to nature. And what is more natural than the sun?

[Read: You’re not allowed to have the best sunscreens in the world]

Now is an apt moment for American politics to become more sun-friendly. Tanning is making a comeback across pop culture, even as “anti-aging” skin care and cosmetic procedures boom. Young people are lying outside when the sun is at its peak—new apps such as Sunglow and Rayz AI Tanning tell them when UV rays are strongest—to achieve social-media-ready tan lines. Last year, Kim Kardashian showed off a tanning bed in her office (in response to backlash, she claimed that it treated her psoriasis). Deep tans are glorified in ads for luxury goods, and makeup is used in fashion shows to mimic painful-looking burns. Off the runway, “sunburned makeup,” inspired by the perpetually red-cheeked pop star Sabrina Carpenter, is trending.

Veena Vanchinathan, a board-certified dermatologist in the Bay Area, told me that she’s noticed more patients seeking out self-tanning products and tanning, whether in beds or outdoors. Angela Lamb, a board-certified dermatologist who practices on New York’s well-to-do Upper West Side, told me her patients are curious about tanning too. “It’s actually quite scary,” she said. A recent survey by the American Academy of Dermatology found that a quarter of Americans, and an even greater proportion of adults ages 18 to 26, are unaware of the risks of tanning, and many believe in tanning myths, such as the idea that a base tan protects against a burn, or that tanning with protection is safe. (“There is no such thing as a safe tan,” Deborah S. Sarnoff, the president of the Skin Cancer Foundation, told me.)

Recently, some experts have called for a more moderate approach to sun safety, one that takes into account the benefits of some sun exposure and the harms of too much shade. “I actually think we do ourselves a bit of a disservice and open ourselves up to criticism if the advice of someone for skin-cancer prevention is ‘Don’t go outside,’” Jerod Stapleton, a professor at the University of Kentucky who studies tanning behaviors, told me. But the popular rejection of sun safety goes much further. Advances in skin-cancer treatment, for example, may have lulled some Americans into thinking that melanoma just isn’t that serious, Carolyn Heckman, a medical professor at Rutgers University’s Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, told me. Skin-cancer treatment and mortality rates have indeed improved, but melanomas that metastasize widely are still fatal most of the time.

[From the June 2024 issue: Against sunscreen absolutism]

In previous decades, tans were popular because they conveyed youth, vitality, and wealth. They still do. (At least among the fairer-skinned; their connotations among people of color can be less positive.) But the difference now is that tanning persists in spite of the known consequences. Lamb likened tanning to smoking: At this point, most people who take it up are actively looking past the well-established risks. (Indeed, smoking is also making a pop-culture comeback.) A tan has become a symbol of defiance—of health guidance, of the scientific establishment, of aging itself.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

Editor’s Note: Washington Week With The Atlantic is a partnership between NewsHour Productions, WETA, and The Atlantic airing every Friday on PBS stations nationwide. Check your local listings, watch full episodes here, or listen to the weekly podcast here.

This week, Congress passed Donald Trump’s request to claw back $9 billion in approved federal spending, including funding for foreign aid and public broadcasting. Panelists on Washington Week With The Atlantic joined last night to discuss the president’s rescissions request—and what its approval may signal about future appropriations.

“What I think will be remembered of this vote is it was a test case in whether” Republicans in Congress “could change the way the government appropriates money,” Michael Scherer, a staff writer at The Atlantic, said last night.

Historically, Scherer explained, even when one party controls both chambers of Congress, 60 votes are still required to pass a budget through the Senate. “That means you need a bipartisan process,” he continued. But this differs from a rescissions request, which can pass with only 51 votes. The Trump administration’s goal, Scherer argued, is to break away from a bipartisan budgeting process “by making it a purely partisan” one. This, Scherer said, could “change dramatically the whole way the federal government’s been budgeted for years.”

Joining the editor in chief of The Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg, to discuss this and more: Leigh Ann Caldwell, the chief Washington correspondent at Puck; Stephen Hayes, the editor of The Dispatch, Meridith McGraw, a White House reporter at The Wall Street Journal; and Michael Scherer, a staff writer at The Atlantic.

Watch the full episode here.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

In a court document filed earlier this month, the Internal Revenue Service quietly revealed a significant break with long-standing practice: Churches will no longer risk their nonprofit status if clergy endorse political candidates from the pulpit. The change stemmed from a lawsuit brought against the agency by evangelical groups that argued that the prior ban on church involvement in political campaigns infringed upon their First Amendment rights. Their victory, though, may turn out to be a Faustian bargain: Churches can now openly involve themselves in elections, but in doing so, they risk becoming de facto political organizations. What may appear to be a triumph over liberalism could in fact be a loss, the supersession of heavenly concerns by earthly ones.

Churches have long been divided over the proper role for religion in American politics. One approach has been to militate against the separation of church and state, insofar as that distinction limits what churches can do to exercise power in society. The IRS change, along with several others by the Trump administration, will soften that barrier, allowing churches to take on a much more pronounced role in electoral politics. Another approach has been to operate within the confines of that separation—which has produced some very noble results: a norm of discouraging churches from turning into mere organs of political parties, and an emphasis on forming the conscience of believers rather than providing direct instructions about political participation.

A conservative 30 years ago might have preferred that latter approach, or at least said so. Back then, members of the right complained that Black churches frequently gave political endorsements or raised funds for electoral campaigns, and that the IRS neglected to enforce its now-eliminated ban, known as the Johnson Amendment. Yet by 2016, that dynamic had reversed, leading Donald Trump, then still a presidential candidate, to court the coveted right-wing evangelical vote by vowing to destroy the amendment once in office. A number of religious leaders took the implications of that promise and ran with them—an investigation by The Texas Tribune and ProPublica published in 2022 found that plenty of evangelical churches were offering endorsement despite the rule. The hope in paring down the Johnson Amendment is apparently that church endorsements will influence the outcome of elections in the right’s favor.

[Elizabeth Bruenig: Progressive Christianity’s bleak future]

But there’s little reason to believe that church endorsements will do much in the way of persuasion. American churches have already undergone so much liberal attrition that, in practice, many right-wing evangelical pastors will be instructing their congregations to vote for candidates most members already intend to vote for. To the degree that broadly conservative churches retain some liberal members, endorsing right-wing candidates seems like just the thing to alienate them, which is a loss for those congregations as well as for the faith as a whole. Church intervention in particular electoral races is an efficient polarization machine.

For that and other reasons, this policy shift doesn’t really offer any benefits to Christians quaChristians. Providing political endorsements makes churches susceptible to powerful campaign tactics: PACs, for example, will have incentives to fund churches that reflect their agendas, meaning that pastors’ livelihoods could come to depend on contorting their religious beliefs to suit political interests. Politically active congregants will also have good reason to lobby their pastors for certain endorsements, another source of pressure for church leaders to say that supporting a particular candidate is the will of God. And the practice of offering endorsements prioritizes accepting specific instructions from church leaders over cultivating Christian values and methods of reasoning that allow the faithful to determine which candidates to support for themselves. (Indeed, the Christian religion itself seeks to cultivate those very things for that very reason, rather than providing an itemized list of every behavior to perform and every behavior to avoid.) This is apparently why the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a statement that Catholic clergy will still decline to make political endorsements. “The Church seeks to help Catholics form their conscience in the Gospel,” the release read, “so they might discern which candidates and policies would advance the common good.”

That is a much more logical way for church leaders to proceed. Dictating which candidates to vote for is at once presumptuous, assuming much more about God’s judgment than can rightly be accounted for, and also nihilistic, assuming that churchgoers are so ill-formed in their faith that they can’t be trusted to figure out the right answers to these earthly, prudential questions. Granting the imprimatur of the faith to ordinary charlatans—the most common breed of politician—is ill-begotten, and borders on sacrilegious.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

Defending mainstream journalism these days is about as appealing as doing PR for syphilis. Nonetheless, here I am. Back in February, Attorney General Pam Bondi invited a group of MAGA influencers to the White House to receive what was billed as “Phase 1” of the government’s files on Jeffrey Epstein, the wealthy sex offender who died in jail in 2019. The 15 handpicked newshounds included Jack Posobiec, promoter of the Pizzagate conspiracy theory; Chaya Raichik, whose Libs of TikTok social-media account itemizes every single American schoolteacher with blue hair and wacky pronouns; and the comedian Chad Prather, performer of the parody song “Beat That Ass,” about the secret to good parenting. Also present was DC_Draino, whose name is a promise to unclog the sewers of the nation’s capital.

The chosen ones duly emerged bearing ring binders and smug expressions—only to discover that most of the information that the government had fed them had already been made public. Several of the influencers have since complained that the Trump administration had given them recycled information. They couldn’t seem to understand why White House officials treated them like idiots. I can help with this one. That’s because they think you are idiots.

[Read: Trump’s Epstein answers are getting worse]

The harsh but simple truth is that powerful people, including President Donald Trump, do not freely hand out information that will make them look bad. If a politician, PR flak, or government official is telling you something, assume that they’re lying to you or spinning or—at best—coincidentally telling you the truth because it will damage their enemies. “We were told that more was coming,” Posobiec complained, but professional commentators should be embarrassed about waiting for the authorities to bless them with scoops. That’s not how things work. You have to go and find things out. Reporters do not content themselves with “just asking questions”—the internet conspiracist’s favored formulation. They gather evidence, check facts, and then decide what they are confident is true. They don’t just blast out everything that lands on their desk, in a “kill ’em all, let God sort ’em out” kind of way.

That’s because some conspiracy theories turn out to involve actual conspiracies, and the skill is separating the imagined schemes from the real ones. Cover-ups do happen. In Britain, where I live, the public has recently learned for certain that a military source accidentally leaked an email list of hundreds of Afghans who cooperated with Western forces, possibly exposing them to blackmail or reprisals. The leak prompted our government to start spending billions to secretly relocate some of the affected Afghans and their families. All the while, British media outlets—which are subject to far greater legal restrictions on publication than their American counterparts—were barred from reporting not only the contents of the leaked list, but its very existence. Several news organizations expended significant time and money getting that judgment overturned in court.

Earlier this month, the government released a memo declaring that the Department of Justice and the FBI had determined that “no further disclosure would be appropriate or warranted” in the Epstein case. Since then, Trump-friendly influencers have struggled to supply their audience’s demands for more Epstein content while preserving their continued access to the White House, which wants them to stop talking about the story altogether. Because these commentators define themselves through skepticism of “approved narratives” and decry their enemies as “regime mouthpieces,” their newfound trust in the establishment has been heartwarming to see.

Some of the same people who used to cast doubts about the government’s handling of the Epstein case are now running that government. “If you’re a journalist and you’re not asking questions about this case you should be ashamed of yourself,” J. D. Vance tweeted in December 2021. “What purpose do you even serve?”

I would be intrigued to hear a response to that challenge from Dinesh D’Souza, who said on July 15 that “even though there are unanswered questions about Epstein, it is in fact time to move on.” Or from Charlie Kirk, who said a day earlier: “I’m done talking about Epstein for the time being. I’m gonna trust my friends in the administration. I’m gonna trust my friends in the government.” Or from Scott Adams, the Dilbert creator, who wrote: “Must be some juicy and dangerous stuff in those files. But I don’t feel the need to be a backseat driver on this topic. Four leaders I trust said it’s time to let it go.” (For what it’s worth, some influencers, such as Tucker Carlson, have refused to accept the Trump administration’s official line that there’s nothing to see here. I’m not alone in thinking this reflects a desire to outflank anyone tainted by, you know, actual government experience when competing for the affections of the MAGA base in 2028.)

For all right-wing influencers’ claims of an establishment cover-up, most of the publicly known facts about the Epstein case come from major news outlets. In the late 2000s, when few people were paying attention, The New York Times faithfully chronicled Epstein’s suspiciously lenient plea deal—in which multiple accusations of sexual assault on teenage girls were reduced to lesser prostitution charges—under classically dull headlines such as “Questions of Preferential Treatment Are Raised in Florida Sex Case” and “Amid Lurid Accusations, Fund Manager Is Unruffled.” After Epstein’s second arrest, the paper reported on how successfully he had been able to rehabilitate himself from his first brush with the law, prompting awkward questions for Bill Gates, Prince Andrew, and other famous faces.

Epstein’s second arrest might not have happened at all without the work of Julie Brown of the Miami Herald. She doggedly reported on how Trump’s first-term labor secretary, Alexander Acosta, had overseen the plea deal when he was a U.S. attorney in Florida. She found 80 alleged victims—she now thinks there might have been 200—and persuaded four to speak on the record. Around the time that Epstein was wrapping up a light prison sentence in 2009, newsroom cuts at the Herald had forced Brown to take a 15 percent pay reduction. Sometimes she paid her own reporting expenses.

[Listen: The razor-thin line between conspiracy theory and actual conspiracy]

Over the past two decades, the decline of classified advertising, along with the rise of social media, has left America with far fewer Julie Browns and far more DC_Drainos. This does not feel like progress. The shoe-leather reporters of traditional newspapers and broadcasters have largely given way to a class of influencers who are about as useful as a marzipan hammer in the boring job of establishing facts. In May, Trump’s press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, scheduled a series of special influencers-only briefings, and I watched them all—surely reducing my future time in purgatory. None of the questions generated a single interesting news story.

In recent days, while MAGA influencers have muttered online about the release of camera footage from outside Epstein’s cell on the night of his death, Wired magazine found experts to review the video’s metadata, establishing that it had been edited, and a section had been removed. Yesterday, The Wall Street Journal—whose conservative opinion pages make its news reporting harder for the right to dismiss—published details of a 50th-birthday message to Epstein allegedly signed by Trump in 2003. The future president reportedly included a hand-drawn picture of a naked woman and told the financier, “May every day be another wonderful secret.” (Trump has described this as a “fake story,” adding: “I never wrote a picture in my life.” In fact, Trump has donated a number of his drawings to charity auctions.)

Legacy news outlets sometimes report things that turn out not to be true: Saddam Hussein’s imaginary WMDs, the University of Virginia rape story. But that’s because they do reporting. It’s easier not to fail when you don’t even try.

We now have a ridiculous situation where influencers who bang on about the mainstream media are reduced to relying on these outlets for things to talk about. Worse, because no issue can ever be settled as a factual matter, the alternative media is a perpetual-motion machine of speculation. MAGA influencers want the truth, but ignore the means of discovering it.

At the heart of the Epstein story is a real conspiracy, as squalid and mundane as real life usually is. The staff members who enabled Epstein; the powerful friends who ignored his crimes; and the prosecutors who downgraded the charges back in the late ’00s. If the Epstein scandal teaches us anything, it is that America needs a dedicated and decently funded group of people whose job is not just to ask questions, but to find answers. Let’s call them journalists.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

As the questions surrounding Jeffrey Epstein’s life and death—questions that Donald Trump once helped whip up—tornadoed into their bajillionth news cycle, the president’s team began to privately debate ways to calm the furor: appoint a special counsel to investigate. Call on the courts to unseal documents related to the case. Have Attorney General Pam Bondi hold a news conference. Hold daily news conferences on the topic, à la Trump’s regular prime-time pandemic appearances.

It dismissed every option. Any decision would ultimately come from Bondi and Trump together—or from Trump alone—and for days, the president was adamant about doing nothing.

Trump was annoyed by the constant questions from reporters—had Bondi told him that his name, in fact, was in the Epstein files? (“No,” came his response)—and frustrated by his inability to redirect the nation’s attention to what he views as his successes, four White House officials and a close outside adviser told us. But more than that, Trump felt deeply betrayed by his MAGA supporters, who had believed him when he’d intimated that something was nefarious about how the Epstein case has been handled, and who now refused to believe him when he said their suspicions were actually baseless.

[Jonathan Chait: Why Trump can’t make the Epstein story go away]

He—the president, their leader, the martyr who had endured scandals and prosecution and an assassin’s bullet on their behalf—had repeatedly told them it was time to move on, and that alone should suffice. Why, he groused, would the White House add fuel to the fire, would it play into the media’s narrative?

In particular, Trump has raged against MAGA influencers who, in his estimation, have profited and grown famous off their association with him and his political movement, according to one of the officials and the outside adviser, who is in regular touch with the West Wing. They and others we spoke with did so on the condition of anonymity because they did not want to anger Trump by talking about a subject that has become especially sensitive. Trump told the outside adviser that the “disloyal” influencers “have forgotten whose name is above the door.”

“These people cash their paychecks and get their clicks all thanks to him,” the adviser told us. “The president has bigger fish to fry, and he’s said what he wants: Move on. People need to open their ears and listen to him.”

But Trump’s haphazard efforts at containment—specifically, his effort to simply bulldoze through this very real scandal—came to an end last night, when The Wall Street Journal published an explosive story about a bawdy 50th-birthday letter that Trump allegedly sent to Epstein, which alluded to a shared “secret” and was framed by a drawing of a naked woman’s outline. (Trump denied writing the letter or drawing the picture, and has threatened to sue the paper.) Shortly after the article posted online, Trump wrote on Truth Social that because of “the ridiculous amount of publicity given to Jeffrey Epstein,” he has asked Bondi to produce all relevant grand-jury testimony related to the Epstein case. Bondi immediately responded, writing, “President Trump—we are ready to move the court tomorrow to unseal the grand jury transcripts.”

The Journal story underscored, yet again, the part of the Epstein saga that Trump and his allies most wish would go away: that Trump was one of Epstein’s many famous pals and had a long—and public—friendship with the hard-partying, sex-obsessed financier who pleaded guilty in 2008 to two prostitution-related crimes and became a registered sex offender. Chummy photos of the two men, including at Trump’s private Mar-a-Lago Club, abound; from 1993 to 1997, Trump flew on Epstein’s private jets seven times, according to flight logs that emerged at an Epstein-related trial; in a 2002 New York magazine profile of Epstein, Trump said he’d known Epstein for 15 years and praised him as a “terrific guy.”

“He’s a lot of fun to be with,” Trump enthused to the magazine. “It is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side.” The two reportedly had a falling-out in 2004 when Epstein bought an oceanfront Palm Beach mansion that Trump wanted.

On Wednesday—after the White House had been alerted that the Journal was working on a big story, but at a moment when it still thought it might be able to kill it—Trump took to social media to blast as “past supporters” Republicans still discussing the Epstein matter. He also tore into them during an Oval Office appearance with the crown prince of Bahrain. The president declared that “some stupid Republicans and foolish Republicans” had fallen for a hoax that he said had been created by the Democrats. The president also privately fumed at House Speaker Mike Johnson’s call for “transparency”—and for Trump’s Justice Department to release more files related to the Epstein case—while White House aides wondered if the apparent split could lead to further Republican defiance on other issues.

[Helen Lewis: ‘Just asking questions’ got no answers about Epstein]

Still, before the Journal story changed the stakes yet again, Trump did not have plans to make additional calls to MAGA media allies or Republican lawmakers, one of the officials told us; instead, the president believed that his public comments and Truth Social posts were sufficient. (Despite his ire, he did not, for instance, reach out to Johnson or his team.)

“He’s being tested and doesn’t like it,” the official told us. “He doesn’t want to talk about it.”

Former New York Governor Mario Cuomo once observed, “You campaign in poetry; you govern in prose.” And although the country does sometimes accept politicians who campaign in poetry and govern in prose, it is less willing to countenance those who campaign in conspiracy theory and then govern in a nothing-to-see-here-folks reality.

Epstein pleaded guilty in Florida state court in 2008 and was convicted of procuring a child for prostitution and of soliciting a prostitute. He received a generous (and controversial) plea deal and served a short prison sentence before being released. He was arrested again in August 2019 and accused of sex-trafficking minors, leading some to wonder who else in Epstein’s powerful orbit might have been involved and also face charges. He died a month later. Getting to the bottom of the details surrounding Epstein’s death in jail while awaiting trial—which has been ruled a suicide—and releasing additional information about Epstein’s sexual abuse of young women, and whether other well-known figures were involved, was never a top Trump-campaign promise. Trump answered when asked, but it was not a mainstay of his stump speech, something he regularly read from the teleprompter or riffed about at rallies.

Nevertheless, when Trump retook office, his supporters were eager for a big reveal. The wave began to crest when Bondi, asked in a February Fox News interview if she would release a list of Epstein’s clients, replied, “It’s sitting on my desk right now to review.” Less than a week later, she did herself no favors when, with much fanfare, she invited MAGA influencers to the White House to receive what she claimed were binders full of the declassified Epstein files, only for the beaming, gleeful sleuths to realize that the most scandalous thing about the binders was just how little information they contained. But a two-page memo that the Department of Justice released last Monday—which, in bureaucratese, offered a version of Trump’s current time-to-move-on mantra—is what finally sent the MAGA wave crashing down on Bondi and the president.

Laura Loomer, a Trump ally and far-right provocateur who called for Bondi to be fired over the memo, told us on Wednesday that she is sensitive to the challenges of separating fact from fiction—but that although not everyone in Epstein’s orbit is inherently guilty, those who are guilty should be revealed. “They’re trying to say there’s no list,” she said. “There’s a difference between people who were caught on video engaged in foul pornography and people who were caught in Jeffery Epstein’s contact list.” Demonizing everyone in Epstein’s purported black book would be like tying her to the misdeeds of everyone saved in her cellphone—“I have 7,000 contacts,” she said—“but they should release the names of the people involved in the child pornography.” Although Loomer and others have raised questions about video recordings of child sexual abuse collected by investigators, Bondi has said that Epstein downloaded those videos and that they were not records of crimes committed by him or his friends.

Loomer has also publicly called for a special counsel to investigate the Epstein case and release the files. In our conversation, she reiterated that appeal and suggested that having “Pam Blondi”—her derisive nickname for the flaxen-haired attorney general—“apologize for either deliberately lying or overexaggerating” her claim that the key files sitting on her desk in February would help to mitigate the base’s angst. Still, Loomer acknowledged, a Bondi apology would at this point be but “one step.” “Obviously, now this has taken on a life of its own,” she observed.

The Epstein news cycle has also distracted from the accomplishments Trump hopes to showcase—his trade deals, the massive legislative package he just muscled through—and has embroiled his West Wing in a familiar cycle of drama. As the MAGA movement turned not just on Bondi but also on FBI Director Kash Patel and his deputy, Dan Bongino, over their handling of the Epstein files, tensions among the three became public. Bongino and Patel seemed to blame Bondi for their reputational hit, and last Friday, Axios reported that Bongino had simply refused to show up for work. Trump was upset with Bongino and Patel, and Vice President J. D. Vance was dispatched as a behind-the-scenes peacemaker. (A White House official told us that the president has no plans to fire Bondi, Bongino, or Patel, but noted pointedly that Trump is very supportive of Bondi, and merely supportive of the other two.)

What additional information could, and should, be revealed remains genuinely unclear. Questions worthy of further scrutiny were raised by Wired’s recent reporting on the footage that the Justice Department released from the lone security camera near Epstein’s jail cell the night before he was found dead; the video’s metadata were shown to have likely been modified, and nearly three full minutes were cut out. But it is also possible that Epstein kept no written log of his crimes, and that whatever has not yet been released is simply to protect Epstein’s victims. (There is also, of course, the competing theory that information is being withheld to protect Trump, or others close to him.)

[Listen: The razor-thin line between conspiracy theory and actual conspiracy]

The White House official told us that the Justice Department did a thorough investigation and that much of what remains unreleased falls into one of these categories: documents that are sealed by courts (though Trump and Bondi’s Thursday appeal may change that); child pornography; and material that could expose any additional third parties to allegations of illegal wrongdoing.

This, perhaps, has been the most confusing and upsetting part for Trump: his inability to manage his uber-loyallists and regular allies. In June, during an unrelated fight with Elon Musk—Trump’s on-again, off-again benefactor and buddy—Elon posted on X, “Time to drop the really big bomb: @realDonaldTrump is in the Epstein files. That is the real reason they have not been made public.” He later deleted the post, but more recently, as the Epstein controversies resurfaced, he again posted an appeal for further disclosure. “How can people be expected to have faith in Trump if he won’t release the Epstein files?” Musk wrote.