Subscribe here: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Pocket Casts

Five years ago, The Atlantic published Floodlines, an eight-part podcast that told the story of Hurricane Katrina and of the people in New Orleans who survived it. The show detailed the ways that failures of federal and local policies concerning flood control and levees created the flood that submerged New Orleans in 2005, and also the ways that preexisting social inequalities marked some people for disaster and spared others. Through the recollections of people who survived Katrina, as well as officials who tried to coordinate a response, Floodlines explored how misinformation, racism, and ineptitude shaped that response, and how Black and poor New Orleanians were pushed away from their homes. In particular, the series follows the story of Le-Ann Williams, who was 14 when the levees broke.

As the 20th anniversary of Katrina arrives, the city of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast are still dealing with the legacy of the flood and with the racial inequality and displacement that were at the heart of the series. The Black population of New Orleans is declining, and some neighborhoods still haven’t come back. Many people who were forced to leave home in 2005 are unable to afford to rent or own where they built their pre-Katrina lives. Experts wonder if the flood-control system there is truly ready for the next “big one,” and because of climate change, more and more cities and towns may face similar threats. Help from FEMA is tenuous under a Trump administration that has slashed its resources and threatened to phase out the department altogether.

So on the occasion of this anniversary, Floodlines takes a fresh visit to New Orleans, to reconnect with Le-Ann Williams, and with her daughter, Destiny. In this special episode, we spend a day with Williams’s family and learn about the heartbreaks, tragedies, and triumphs they’ve experienced since we last spoke. We learn how trauma from Katrina still lives on in the hearts and minds of its survivors, and how, for the generation born after the flood, a disaster they never witnessed still governs their lives.

The following is a transcript of the episode:

Vann R. Newkirk II: (Knocks on metal door.)

Male voice: Who’s that?

Vann Newkirk: It’s Vann!

Male voice: Come on.

Newkirk: All right. (Chuckles.) How you doing?

Le-Ann Williams: Hey, Vann!

Newkirk: Hey, how you doing?

Williams: How y’all doing? All right.

Newkirk: Well, hey. It’s Vann Newkirk. I know it’s been a minute since you’ve heard from me here. Five years, to be exact.

Williams: My family: my mom, Patricia; my daughter, Destiny; and my cousin Tasha.

Newkirk: Nice to meet y’all. And I heard a lot about y’all. Nice to meet y’all.

Newkirk: A lot has happened in the time since we put out Floodlines. The pandemic started to really shut everything down the day we put out the show, and it’s been one thing after another since then. There’s been economic chaos. There were elections. There was an insurrection. There’ve been fires and hurricanes and floods. There’s been a lot of death and a whole lot of grief. A lot of people live different lives than they did in 2020. Hell, I know I do.

Five years ago, when I was making Floodlines, I’d been thinking about Richard, the enslaved man who survived the hurricane in 1856 at Last Island, Louisiana.

Newkirk (Floodlines clip): The next morning, the only building still standing on Last Island was that stable. Richard and the old horse had made it. Many other folks weren’t so lucky.

Newkirk: I was interested in memory and what disasters reveal about a place. My reporting took me to meeting somebody who, quite frankly, changed my life.

Williams (Floodlines clip): We’ll have the trumpet player, the trombone player, the snare-drum player, the bass-drum player, and the tuba players will have sticks blowing.

Newkirk: Le-Ann Williams. You remember Le-Ann. She was 14 years old.

**Williams (Floodlines clip):**I had this crush on this boy named Fonso Jones—

Newkirk: She grew up around Treme and Dumaine Street—

Williams (Floodlines clip):—and Fonso was the point guard.

Newkirk: —living in the Lafitte housing projects, when Hurricane Katrina came and the levees broke.

**Williams (Floodlines clip):**And we heard it on the radio, and a man was like, he was in a panic: I repeat, get to safety; get to the Superdome.

Newkirk: She and her family went on an odyssey after the flood. And she came back to a totally different city.

Archival (Floodlines clip): 3,000 people a day heading to Texas.

Archival (Floodlines clip): Arkansas will take 20,000 people.

Archival (Floodlines clip): I’m not going back to New Orleans. I don’t wanna go back to New Orleans.

**Williams (Floodlines clip):**If you push us out, what’s gonna be left? Just come look at things, like a museum. Just come and looking at historic places and buildings? That’s it? If you push us out, where the culture gonna come from?

Newkirk: If you haven’t listened to Floodlines, I recommend starting from the beginning. In 2020, when we put the show out, I honestly didn’t know if it would matter that much with so much going on. But I found out that I was wrong.

Archival (news clip): The breaking news: Stay at home. That is the order tonight from four state governors as the coronavirus pandemic spreads. New York, California, Illinois—

Newkirk: Whether it was the early fears of “looting” during the pandemic, or a Black community being destroyed by a fire—

Archival (news clip): Altadena, and this entire hillside is on fire.

**Newkirk: —**or FEMA’s response to Hurricane Helene—

Archival (news clip): The deadliest hurricane for the U.S. since Katrina in 2005.

Newkirk: —people kept coming back to Hurricane Katrina as a point of reference.

Russell Honoré: That’s rumor gets spread. You know, we dealt with that in Katrina too, Laura.

Newkirk: As it turned out, this show about generations of New Orleanians contending with catastrophe, grief, memory, displacement, and being left behind by our government still had some important lessons for the present. In 2020 we left the show’s narrative unfinished, on purpose. Le-Ann, and the others we met—Fred, and Alice, and Sandy, and General Honoré—were all still living with the legacy of Katrina and making meaning from it themselves. They were still living their stories.

But also, as it turns out, I couldn’t quit Floodlines so easily. I’d become connected to the people I’d interviewed, who’d shared their lives with me. I’d spent hours and days talking to them, eating meals with them, hanging out. I cared about what happened to them.

Before, I had been thinking about Richard, but now I was thinking about Le-Ann. After the show came out, I saw that she’d gone through even more tough times. I also saw that she was celebrating: a new home, a new job, a kid who was doing well in school.

So on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Katrina, I decided to visit New Orleans.

Williams: Oh, Lord.

Destiny Richardson: We’re gonna tear you up in them spades.

Williams: Look at her. We gonna tear him up?

Richardson: Mm-hmm.

Williams: We’re gonna tear you in them spades**.**

Newkirk: I don’t know. I ain’t lost in a minute. (Laughs.)

Newkirk: I paid Le-Ann a visit, and talked to her family. And met her daughter, Destiny, for the first time.

Newkirk: When we last spoke, you were what? Eleven?

Williams: Yeah.

Newkirk: Eleven years old, and Le-Ann told us a whole lot about you, so, and she posts about you on Facebook all the time.

Williams: Look what you do.

Richardson: Always.

Newkirk: Always. I’ve seen the honor roll. (Laughs.) You got the honor roll.

Richardson: Yup, honor roll every year.

Newkirk: Congratulations.

Richardson: Two times in a row.

Newkirk: Congratulations.

Richardson: Thank you.

Williams: I’m a proud parent, of course.

Newkirk: Catch me up; catch me up. What’s been going on with you the last five years?

Williams: I changed jobs; I moved. I’m in a different spot. And I’m in a different place than I was five years ago.

Newkirk: What kind of place?

Williams: I’m at a peace state, like letting things go that don’t mean me no good, you know, I’m trying to just go a different route.

Newkirk: I wanted to know more about that different route. So I stayed a little while.

[Music]

Newkirk: From The Atlantic, this is a special episode of Floodlines, “Part IX: Rebirth.”

It’s Sunday, after church time, when we meet Le-Ann. We’re trying to hurry up and talk so we can get back across town to catch a second line before it rains. We’re in Le-Ann’s new home, and the living room is full of family, everybody just shooting the breeze. She rents here and lives with her mother, Patricia, and with Destiny. It’s a quiet street.

Newkirk: What’s this neighborhood we in?

Williams: We in Pontchartrain Park.

Newkirk: Pontchartrain Park. It’s a historic neighborhood.

Williams: Yes, it is.

Newkirk: So last time we met you were out in the East.

Newkirk: Back then, in 2020, Le-Ann lived in a smaller place off a busy road in New Orleans East. She was working around the clock to provide for Destiny. It was far from the part of the city where she’d grown up, and she told us then how much she resented being forced away from the only home she’d known.

New Orleans East was a tough place to live. After the floodwaters receded, it became sort of a holding area for people pushed out from the core of the city by rising rents and gentrification. When Le-Ann was living there, it was known for crime, violence, for food deserts, for pollution, for all the things you don’t want when you’re raising a little girl.

**Williams:**I just feel like we just was forgotten about, pushed into different neighborhoods. And yeah, the East is dangerous—it’s dangerous out there. Don’t pump gas at night. If you’re on E, you just try and make it home on E. (Laughs.) And a lot of crime is happening now, especially with our youth.

When I was a kid, you could easily go to the gym, get on the swimming team, the double-dutch team, anything. They don’t even have activities like that no more, so it’s easy for the youth to get into things and get in trouble. There’s a lot of carjacking. They’re doing that now—for fun.

Newkirk: The East had felt like a magnet for tragedy. And sure enough, in 2023, when Destiny was around the same age Le-Ann had been during Katrina, catastrophe struck again. But this time, it was a more personal kind of storm. Le-Ann’s stepfather, Jeffrey Hills, the man who’d helped raise her and who’d tried to protect her during Katrina, died suddenly in his sleep, at the age of 47. Talking there in Le-Ann’s living room, the loss still felt recent and present.

Williams: That was two years ago.

Newkirk: People say that’s a long time, but that’s not a long time.

Williams: That’s not.

Newkirk: Yeah. How you dealing with it now?

Williams: Better than two years ago, you know? But we still take it day by day.

Newkirk: The room got a little quieter. Everyone was still grieving. Patricia, Le-Ann’s mom, had lost her husband and partner: for Le-Ann, a father in everything but blood. Jeffrey was smart and he loved books, and he’d always taken pride in her academics. Destiny was his only grandchild, and you know he spoiled her.

But Jeffrey wasn’t just a cornerstone of the family. He was a special part of the whole community. If you were in New Orleans, you knew Jeffrey. He was a veteran tuba player in the city, and he’d played with basically all the big brass bands. He taught and mentored young musicians. I’d seen him play before I even met Le-Ann. His name gets mentioned with all the legends who’ve come through here. And just like it had been for them, for Tuba Fats and Kerwin James and all the rest, when he died, his comrades played in his honor.

[Music]

Newkirk: They played for days. And when it came time to put Jeffrey to rest, they threw a second line like you ain’t never seen. All back in the heart of the Sixth Ward, where Le-Ann used to live.

**Williams:**And when he had his funeral and everything, and it felt like the New Orleans before Katrina. His friends from the band, everybody, musicians, every musician we knew was there for him. And it was Jazz Fest time. A lot of people didn’t go to Jazz Fest; they came. He had gigs lined up for Jazz Fest and everything. So a lot of the musicians didn’t go to the Jazz Fest. They came there for his funeral. And my family all was together, everybody was laughing, and it just felt like the Treme area where I grew up in.

Newkirk: It was like a trip back in time. Back when cousins lived down the street and they used to play pitty-pat. It was bittersweet that it took death to bring back a little bit of the old magic.

But there would be more death before long—more people to grieve and more reasons to reminisce on the old days. The day after Jeffrey’s funeral, Le-Ann found out her brother Christian was gone too.

Williams: My brother was staying with me. He died—he got killed two blocks from my house as soon as he left from my house. He got his bike out the yard, and somebody killed him.

Newkirk: Now she had to grieve her stepfather and her brother, and to be a support for everyone else.

All the trauma of Katrina, all the moving and all the setbacks, all the big life changes like becoming a mother: It had all forced Le-Ann to grow up early. Christian’s and Jeffrey’s deaths were like a second growing-up.

For Le-Ann, what this all meant was that she would have to try to be the kind of cornerstone that Jeffrey had been. She felt like the family was being driven apart, and she wanted to do what she could to hold everything together.

Williams: You know, I’m grown, grown now—you know, people depending on me and things like that. I gotta make sure our family get together. (Laughs.)

Newkirk: Do you feel like it’s harder to keep up with people now that you’re spread out?

Williams: Yeah, it is. We probably, you know, say a thing or two on Facebook with each other.

Newkirk: On Sundays like this one, Le-Ann tries to get as many people in one place as she can, to eat and chat or watch Saints games. And during Mardi Gras season, she goes all in. The main event for the family is Endymion. It’s one of the biggest Mardi Gras parades, and every year thousands of people march. It’s a time.

Williams: I made a Facebook page: “Family is going to Endymion.” And we get on there, we say who’s bringing what, and what time, you know, who’s holding the spots down. And we all get together for Endymion every—since I was a kid. And you know, I just kind of keep the tradition going on for our kids.

Newkirk: For her kid. For Destiny.

Newkirk: I know she’s sitting right here, but can you tell us a little more about Destiny?

Williams: Oh my god. Destiny—she’s smart, she is kind, very headstrong. I have a good baby. I do. Beautiful.

Newkirk: She sound like you: smart, headstrong.

Patricia Hills: Yes.

Newkirk: Oh, you think so?

Newkirk: Le-Ann’s mom, Patricia, is there behind me.

Hills: Very smart. Yes.

Newkirk: Mm-hmm.

Hills: Very smart.Just like her mom, very smart.

Williams: Yeah, I’m proud of her. (Laughs.) I am. I’m a proud parent. Like, you know, you tell your child things, and you know it go in one ear and out the other sometimes. But when they actually listen and do what you say, that’s a blessing.

Newkirk: And we heard, you told us Destiny just got your first job, right?

Richardson: Yeah.

Newkirk: How long you been working there?

Richardson: Probably like, what, a month or two now?

Williams: About two months.

Richardson: About two months.

Newkirk: So what’s that, two, three paychecks so far?

Richardson: Yeah, I think so

Williams: Three paychecks.

Richardson: Yeah.

Newkirk: All right, how does that feel?

Richardson: Good. It feels good to have your own money (Laughs.) and buy your own self stuff. I like my job, though. It’s nice. It’s fun. And then you meet a lot of people from, like, all over the world, cause there is like a tourism mall.

Newkirk: In a lot of ways, Destiny is just like any other 16-year-old. She wants to get her license. She had a little marching-band drama. She’s spending those paychecks. She goes to the mall with her friends.

But she’s also dealing with things that would be hard for anyone, let alone a teenager. She’s coping with loss and has witnessed her fair share of violence. Aside from the get-togethers her mom organizes, she doesn’t always have the same closeness to family that Le-Ann did before the flood. It’s like there’s some ghost of Katrina that haunts parts of her life. It’s eerie to see that ghost whenever she watches the old footage in documentaries.

Newkirk: How do you think about Katrina? What’s the first thing that comes to mind?

Richardson: A disaster. It’s like when I watch it, sometimes it’ll be heartbreaking to watch it because you see the people like with their family, babies and all that. It’s hot, nobody to help them. You’re like, these people was really out here for days doing this, trying to get food, nobody coming to help them, water everywhere, clothes sticky. I don’t want to be like that after the hurricane. (Laughs.) It, it was just a lot. Like, a lot to take in, especially for the people I know. It was a lot for them. People dying.

Richardson: That’s a lot.

Newkirk: Well, you look at those documentaries and imagine your mama going through that?

Richardson: I could see her, she’s (Laughs.)—I could just see her scared, nerves bad. She already nerve-racking, now, (Laughs.) so I could just see her (Laughs.) when a hurricane hit there after. Probably worrying my grandma, worrying everybody in the house.

Hills: Yes, yes.

Newkirk: Naturally, Destiny doesn’t have the same fears and anxieties that Le-Ann has. She likes to poke fun at her mother for being skittish whenever a storm comes around. But Le-Ann says she’s learned her lesson. She’s evacuating every time. It doesn’t matter how much Destiny jokes about it.

Richardson: She’ll leave even if it’s a one-category storm—hurricane. She’d be so scared: We leaving, let’s go, we leaving. We ain’t waiting to see if it gets stronger or not. We leaving.

Williams: But she never experienced something like that before, and she never will, because we’re leaving.

Richardson: She leaving. She says she sure won’t go through nothing like that again.

Williams: I don’t care what! No, indeed, I have a child, so I know how my mom and them felt.

Hills: You know, I just remember my baby being scared.

Newkirk: Le-Ann and Patricia walked through the floodwaters together. They have a shared story, and shared memories that I’d heard before, from Le-Ann. Now, hearing things from Patricia’s point of view, as a parent myself, helped me really understand just how agonizing it all was.

Hills: She was the oldest and she got the most experiences, and she knew about it and she was scared and stuff like that.

Williams: Yes indeed.

Hills: When Hurricane Katrina hit and I just remember my baby being scared and asking if Momma, we going to die? And I said, No, we’re not. Honey, I said, God got us. We gonna get outta here.

Newkirk: In that moment, Le-Ann had come to understand just how vulnerable she was. It wasn’t just the storm or the flood. The city and the federal government had turned their backs on her. It all left a mark.

Williams: I said, They gonna leave us here to die. They don’t care. I, I said, I hear stories about, oh, you, you know, Black and this and that and poor communities and you know, these things I hear about, but they actually go through something and live it—that’s something different. Like, Nobody’s coming to save us? I mean, newborn babies out there, they have dead bodies just laying—older folks can’t take it. They just dropping. I’m like, My God, this is real.

Newkirk: And so you said, Never again to that.

Williams: I’m not taking—she’s not going through that. She’s not. Now, just in her mind to worry about something like that, so young, to worry if she’s gonna die or if somebody’s coming to save—no, she would never. Not if I have breath in my body. She’s not waiting on nobody to rescue her. I’m gonna be the one.

[Music]

Newkirk: When I last sat down with Le-Ann, way back in 2020, I played her tape from my interview with the ex–FEMA director Michael Brown.

**Michael Brown (Floodlines clip):**So you tell Le-Ann I’m sorry, but you tell Le-Ann that her responsibility is to understand the nature of the risk where she lives and to be prepared for it. Knowing that somebody’s not going to come—the shining knight in armor is not going to come and rescue her when that fear sets in.

Newkirk: It feels like Le-Ann’s response to that is to become the knight in shining armor for everyone else. To take care of people. To make sure that her daughter and her family never feel abandoned like she did. I asked her if she saw Destiny’s childhood as like an alternate-reality version of her own, one without that abandonment.

Newkirk: You were 14 when you had to leave the city. Destiny is 16. Do you see, maybe, in Destiny what that childhood could have been like without that disaster?

Williams: I think about it. I used to think about it a lot—like, where would I have ended up? Would my life, you know, still be the same? Or would I have went off to college like my daughter wants to do? But now I’m like, I’m where I’m supposed to be exactly. This is where God wants me to be, you know? I’m where I’m supposed to be today.

[Break]

Williams (Floodlines clip): It’s crazy. There’s nowhere in the world I’d rather be than here. I love it. It’s my home. It’s my home. I love New Orleans. I done been to Arizona, Texas, Mississippi after Katrina. Nothing like New Orleans. Nothing’s like New Orleans.

Newkirk: One of the things Le-Ann talks about a lot is how much she loves her new neighborhood. She says it’s safer, and her street is quiet and peaceful. And it’s a bit closer to where she grew up.

Newkirk: It’s better out here?

Williams: Yeah, it’s much better.

Newkirk: It’s pretty out here, and you got the levee right there. You was on the levees in the east, too, so you go up on both. (Laughs.) You still go up there with daiquiris or not?

Williams: (Laughs.) We have wine. We have wine.

Newkirk: You have wine? Okay, so it’s a classy establishment. We have wine.

Williams: Yes, wine. We have our wine nights.

Newkirk: Now Destiny’s the one who goes up to the levee most often, but to walk her mom’s dog, an adorable French bulldog named Frenchy.

Richardson: No, right here!

Newkirk: Right up there?

Richardson: Nah, right here.

Newkirk: I wanted to check it out, so we took a walk together. It’s not like the levee at the old place, where you could climb up and see into the water, which Le-Ann loved to do. But up here, maybe it’s best that the water is out of sight. The levees here overlook the Industrial Canal, where it meets the lake. It’s a critical point in the complex system of flood control that defines New Orleans. In 2005, certain parts of this very neighborhood stood under 15 feet of water after the levees were overtopped. There’s a new floodgate now, built by the good old Army Corps of Engineers, that’s supposed to stop that from happening again. Le-Ann is not so sure.

Williams: We’re sitting in a bowl. Mississippi, Pontchartrain—we’re just surrounded by water. We’re below sea level. So just imagine, the water’s on top of us, and the city’s just down here. The water sits like that, so that’s why we’re below sea level, so the wind is just going down. You can’t go up; you’re going down! So that’s the scary thing about, too, where we live. We’re below sea level. I told you that before.

Richardson: Yeah.

Williams: Like, I explained it.

Richardson: Now you see why I won’t stay down here? That’s another cue for me to go.

Williams: Keep moving, huh?

Newkirk: Destiny is kinda over it. She’s heard a lot about Katrina from her mother. When she was younger, Le-Ann even made her sit through a class she put together for Destiny and her friends.

Williams: Yeah, I had a classroom. I fed them every day. They had lunch and everything, breakfast. They had their lunchtime and then they had their time when their parents come pick them up.

Newkirk: So were you rolling your eyes?

Richardson: Was I?

Williams: And one day we had—they watched the documentary of Katrina and they had to write about it, like different things.

Richardson: Yes**.** My grandpa Jeffrey was in the documentary! Walking in the water with my auntie.

Williams: He was walking with auntie. He in there.

Newkirk: Even with all the teenage eye-rolling, you can tell Destiny is proud of her family’s story, especially of her grandfather. And that brought Le-Ann and Destiny back to talking about Jeffrey. About how much he meant to them, and how he represented what New Orleans used to be. They pulled up a video of his funeral and started reminiscing.

Williams: The band came in the funeral home.

Newkirk: Oh wow!

Williams: Look at how packed it was.

Richardson: It was so pretty.

Williams: My pastor say, I’ve never seen a celebration like this, my God! The band come in the funeral home?

Richardson: Yes, that was nice.

[Music]

Newkirk: Standing here in the grass, by the levees, the sun slipping behind a cloud, we watched together.

**Richardson:**They had so many people out there and so many people in the funeral home.

Williams: When they opened the door.

Richardson: When they open the door, that’s when you really saw the people. All the people wasn’t even in the funeral home.

Williams: Yes.

Richardson: They had beaucoup people standing outside.

Williams: He was well known—a tuba player.

Richardson: They had 11 tubas out there for him.

Newkirk: Oh, wow.

Newkirk: It seems to me like they weren’t just mourning Jeffrey, but also how they’d lived, and who they were. It got Le-Ann to thinking about her childhood in the Sixth Ward, and to telling Destiny stories she’d already heard 100 times.

Williams: We just did that. If my cousin had a tambourine, we’ll sit on a curb and they’ll just make a beat. And we’ll just start doing, like, little songs and stuff like that. That’s what we did with each other. We all say something.

Richardson: Y’all, it’s raining.

Newkirk: And then it started to rain.

Newkirk: We got to move.

Williams: Look at that. Oh Lord, we don’t want the sugar to melt, huh?

Newkirk: I got a gel in my hair. What you talking about?

Williams: Okay!

Newkirk: We split up, and dried out for a little bit. I put some more gel in my hair.

[Music]

Newkirk: In the evening, we met back up with Le-Ann and Destiny at an ice-cream parlor uptown.

Richardson: She’s getting a Creole Clown. He’s dressed up like a clown, the ice cream. I want to take a picture of him for the aesthetic.

Newkirk: Destiny did get that Creole Clown ice cream. For the aesthetic.

Newkirk: So they serve it upside down?

Richardson: And they got whipped cream.

Williams: Girl, he is too cute.

Richardson: Yes.

Newkirk: I thought it would be nice to end my time with Le-Ann and Destiny with an ice cream. Back during Katrina, when Le-Ann was escaping the flood, after she’d waded through rat-infested waters, cut her foot stepping on something sharp, and climbed up onto the baking-hot freeway, she saw a man with a cooler who handed her and her family ice creams.

Williams (Floodlines clip): He saying, Ice cream! Ice cream! It’s hot. I got ice cream, cold drinks, and water! Come on, baby. Get y’all something to drink, and, I know y’all, you know, thirsty and stuff.

Newkirk: She told us she got a strawberry shortcake.

Williams (Floodlines clip): A strawberry shortcake. You know? You ever had one of those? Yeah. It’s good. I got one of them.

Newkirk: The moment has always stuck with me as a symbol of how we misunderstand disaster and, by extension, what really happened during Katrina. There’s still, even today, a misconception that disasters—that this disaster in particular brought out the worst in people. That it exposed some latent savagery or lack of morals. But what I’ve seen, over and over again, is that Katrina really showed just how much people loved each other. How much they loved their communities and their city. What was exposed, though, was how little the country and that city loved them. It feels like, in her own way, Le-Ann is trying to rectify that.

Newkirk: Do you feel like you are like the heart of the family now?

Williams: Yes. And sometimes that get overwhelming. It does.

Newkirk: What do you do when you feel overwhelmed?

Williams: Pray. I pray a lot.

Newkirk: She’s overwhelmed a lot. Being the person everyone else relies on is hard, and it can feel like every single thing is on her shoulders. She’s doing her best to take up the role Jeffrey played, but now she understands how much of a toll that takes on a person.

Williams: It feel like I’m always responsible for everybody, like, everybody. And sometimes I’m like, Who responsible for Le-Ann? You know, having everybody’s back and making sure everybody’s good. And sometimes you’re like, you know, Who has my back?

Newkirk: But she also takes pride now in the fact that people around the city know her and know her story.

Newkirk: Do you feel like, you know, between us and all the other stuff, are you—would you call yourself an ambassador now for New Orleans, for the city?

Williams: Yes, I want to put my city on; I wanna, you know, bring light to my people, you know, in New Orleans, no matter what race you is or not, because we family down here, and I just want to bring attention to that.

[Music]

Newkirk: Le-Ann still believes in her city, and she wants to stake a new claim to it. She wants to own her own home in New Orleans. She’s working as a phlebotomist, and doing her best to support everybody and build up her credit.

Williams: It’s going to take a minute, but I’m going to do it.

Newkirk: So ideally, what’s your dream house look like?

Williams: Oh. Look, I think about it all the time when I just see houses. I’m like, Oh my God, I can’t wait to—especially to have something that, you know, that I got that I can probably leave my child. You know, something I can call my own. Me and Destiny, we right by the lake, we love looking at those houses. We just go through looking at houses, like Oh my God.

Richardson: We’ll be like, Ooh that pool big, their backyard big. That house so big!

Williams: Oh my God, this is living right here. We just, you know—

Newkirk: What color is your dream door?

Williams: I want to say red. (Laughs.)

Richardson: Red?

Williams: Old-school.

Richardson: Yes.

Newkirk: She wants a red door, just like her grandma’s house on Dumaine Street had.

Richardson: A big, big backyard.

**Williams:**We have to have a big backyard. Ooh, yes, indeed. My family is big—I got to have a big backyard.

Newkirk: Le-Ann wants to be able to leave Destiny something of her own in New Orleans. But Destiny is looking at colleges out of state.

Newkirk: So Destiny, if you leave, do you ever see yourself coming back?

Richardson: Probably not. I’ll probably come back for like, events and stuff—probably, like, Mardi Gras and all that. But as far as coming back to stay, no.

Newkirk: It’s the place where mother and daughter seem to differ most. Le-Ann was forced across the country, and then across the city, and has spent her whole life since trying to get back. Destiny wants to see the world for herself, to get out. She’s working hard in school, and she’s looking at colleges out of state. She’s got the grades to leave.

Newkirk: Have you taken any visits yet?

Richardson: No, I ain’t taken no visits yet. They be emailing me and stuff for visits, but I haven’t took no visits.

Williams: They gave her $500.

Richardson: Oh yeah, I had got one of CASE scholarships for Mercer. It’s at home in the envelope. Yeah, and if I go there, they’ll give me $2,000 more, plus the scholarship I’ve been built up on when I graduate.

Newkirk: You already getting scholarships?

Richardson: Yeah.

Newkirk: She’s saying it real low-key-like. All right.

Newkirk: But still, for as much as Destiny maybe wants to get out of New Orleans, she’s got her mother’s story with her. She might not know Katrina firsthand, but she knows the importance of taking care of people.

Newkirk: Anybody tell y’all y’all are pretty similar?

Richardson: Yeah, I hear that a lot.

Newkirk: (Laughs.)

Richardson: They say our personalities are similar.

Williams: My cousin tell me all the time, she was like, You’re hard on her, but she’s really strong minded. You don’t have to worry about her. Destiny knows her way.She was like, You need to give her more credit than what you’re doing because she, you know, she’s a good kid.

Newkirk: Do you—when people compare you to your mother, is that something where you roll your eyes?

Richardson: Yes, I be like, Oh my God. (Laughs.) They’d be, like, Aw, girl, you act just like your mama and how she acted when she was younger, but just a little bit more—better or something. I was like, Ah, girl. Here they go with this again.

Newkirk: Le-Ann wants to protect Destiny, and to give her the things she didn’t have. But I wonder if maybe she’s got it backwards. Maybe her family has the thing that other families, rich and poor, Black and white, need. Maybe they’ve got what other people are searching for. The things we lost in our own personal floods over the past five years: family, community, and connection. We lost memory; we lost time. What we need is care.

Newkirk: So how was the ice cream?

**Richardson:**That was good.

Williams: It was.

Richardson: I’m gonna most definitely get that again.

Newkirk: The clown, the clown was solid?

**Richardson:**Yeah, he’s still got his eyes and his hat.

Newkirk: Okay. If I could eat dairy, you know—

Richardson: You can’t eat dairy? You should’ve told me! I would have picked something else. (Laughs.)

Newkirk: No, this is fine. This is fine. Look, between the dairy and the shellfish, I come here and I fast.

Newkirk: We finished our ice creams and walked out into the summer. And then Le-Ann and Destiny went home.

[Music]

Floodlines is a production of The Atlantic. This episode was reported and produced by me and Jocelyn Frank. The executive producer of audio, and our editor, is Claudine Ebeid. Our managing editor is Andrea Valdez. Fact-check by Will Gordon.

Music by Chief Adjuah and Anthony Braxton.

Sound design, mix, and additional music by David Herman. Special thanks to Nancy DeVille.

You can support our work, and the work of all Atlantic journalists, when you subscribe to The Atlantic at TheAtlantic.com/Listener.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

Illustration by The Atlantic. Sources: csa-archives / Getty

Illustration by The Atlantic. Sources: csa-archives / Getty Illustration by Zeloot

Illustration by Zeloot

Abdul Saboor / ReutersCrowds cheer on riders during Stage 21 of the Tour de France, in Paris, on July 27, 2025.

Abdul Saboor / ReutersCrowds cheer on riders during Stage 21 of the Tour de France, in Paris, on July 27, 2025. Artur Widak / Anadolu / GettySpurt, an Australian shepherd, performs an obstacle run during Wild Wild Woof, at the 2025 KDays festival, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, on July 26, 2025.

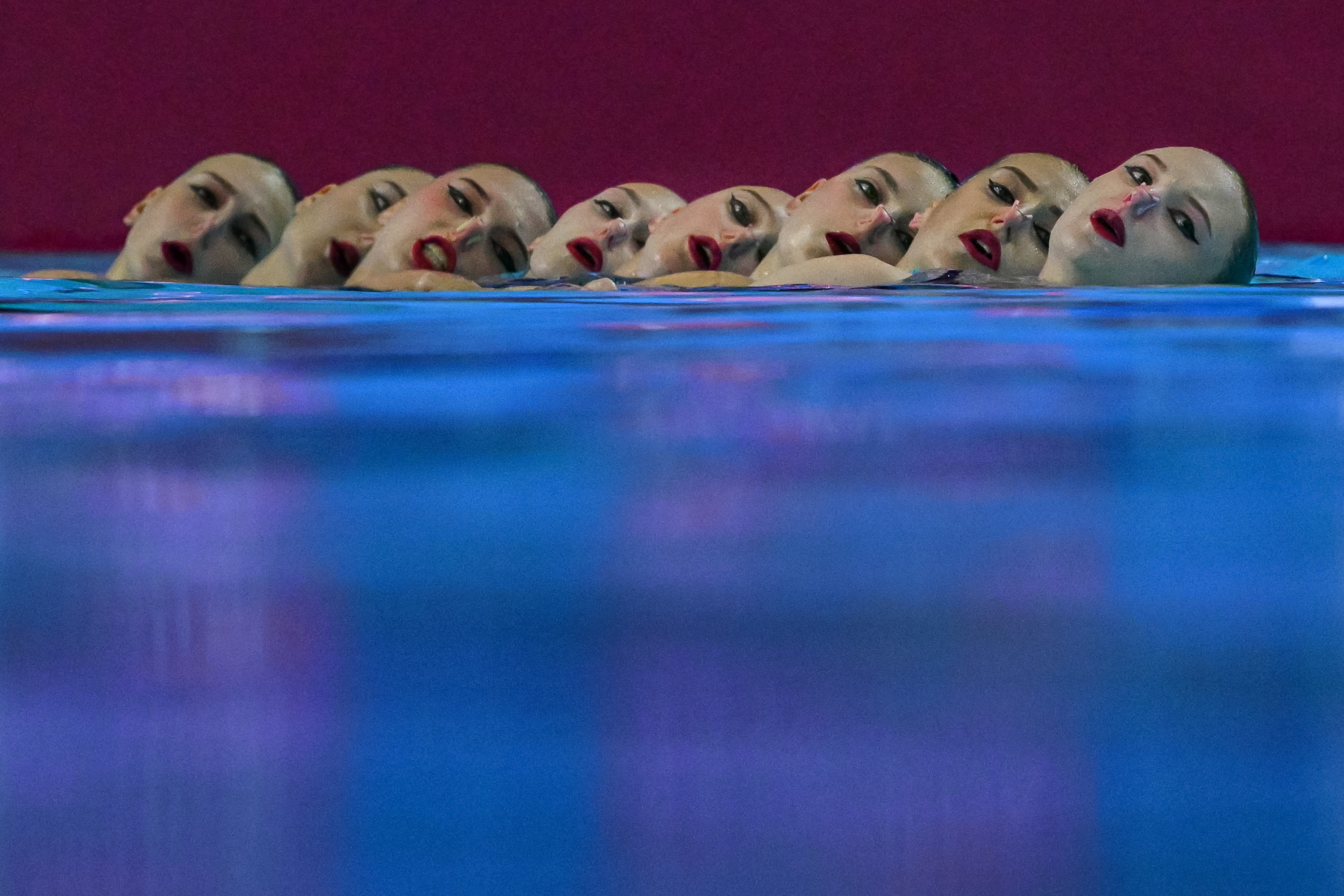

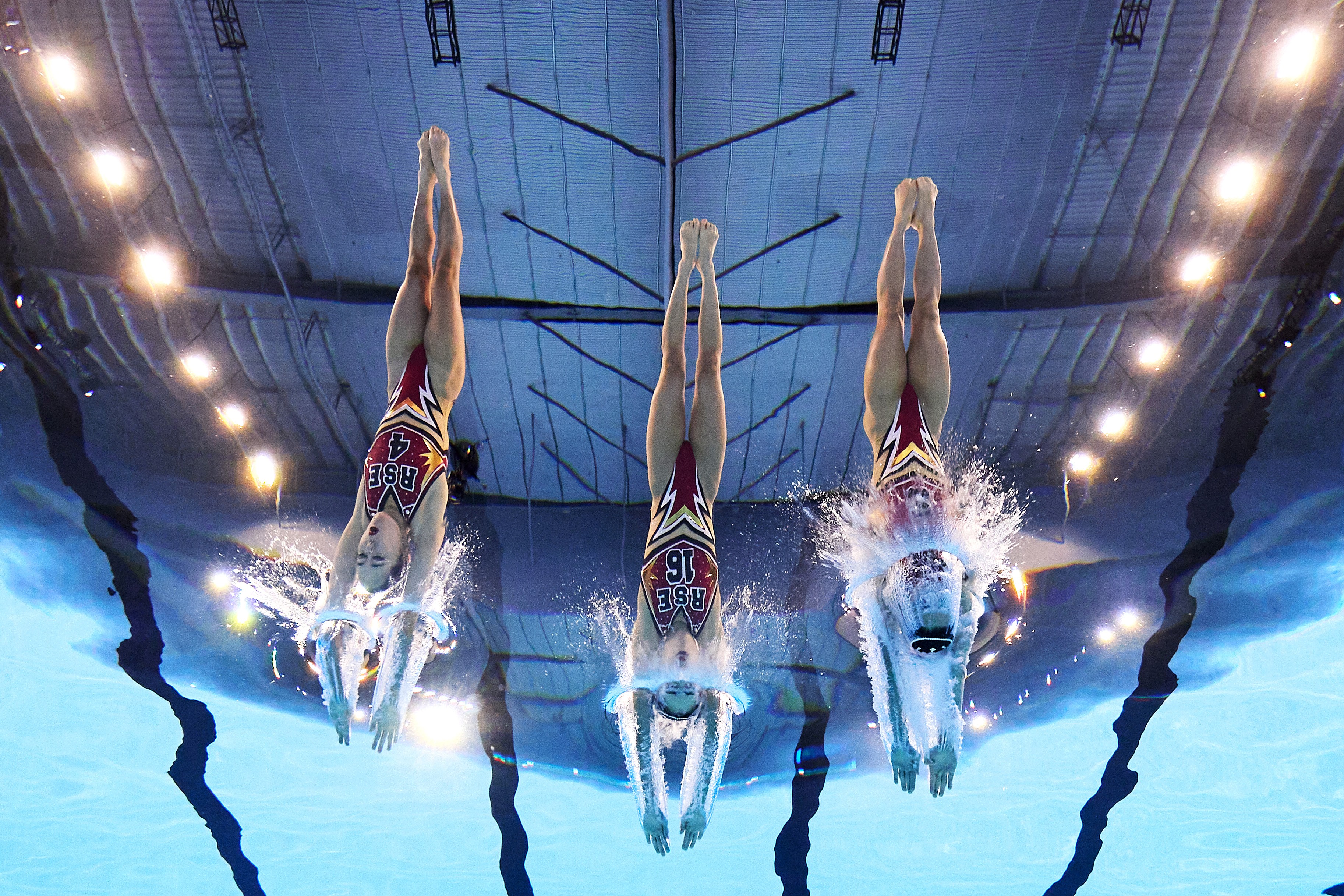

Artur Widak / Anadolu / GettySpurt, an Australian shepherd, performs an obstacle run during Wild Wild Woof, at the 2025 KDays festival, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, on July 26, 2025. Yong Teck Lim / GettySabina Makhmudova of Team Uzbekistan competes in the women's solo free preliminaries on Day 10 of the World Aquatics Championships, in Singapore, on July 20, 2025.

Yong Teck Lim / GettySabina Makhmudova of Team Uzbekistan competes in the women's solo free preliminaries on Day 10 of the World Aquatics Championships, in Singapore, on July 20, 2025. Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times / GettyFreestyle-motocross rider Taka Higashino does a no-hands Superman trick high over the beach, with Catalina Island in the background, on opening day at the U.S. Open of Surfing, in Huntington Beach, California, on July 26, 2025.

Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times / GettyFreestyle-motocross rider Taka Higashino does a no-hands Superman trick high over the beach, with Catalina Island in the background, on opening day at the U.S. Open of Surfing, in Huntington Beach, California, on July 26, 2025. Ronen Tivony / NurPhoto / GettyAn anhinga flips a fish into a headfirst position just before swallowing it, in Lake Eola Park, in Orlando, Florida.

Ronen Tivony / NurPhoto / GettyAn anhinga flips a fish into a headfirst position just before swallowing it, in Lake Eola Park, in Orlando, Florida. Eric Gay / APAngel Hernandez power washes a dinosaur figure at the Witte Museum, in San Antonio, on July 29, 2025.

Eric Gay / APAngel Hernandez power washes a dinosaur figure at the Witte Museum, in San Antonio, on July 29, 2025. Juan Karita / APAn Aymara woman and her llama participate in the 15th National Camelid Expo, in El Alto, Bolivia, on July 26, 2025.

Juan Karita / APAn Aymara woman and her llama participate in the 15th National Camelid Expo, in El Alto, Bolivia, on July 26, 2025. Anthony Devlin / GettyParticipants dance during a performance in tribute to the Emily Brontë–inspired Kate Bush song “Wuthering Heights,” in Haworth, England, on July 27, 2025.

Anthony Devlin / GettyParticipants dance during a performance in tribute to the Emily Brontë–inspired Kate Bush song “Wuthering Heights,” in Haworth, England, on July 27, 2025. Indranil Mukherjee / AFP / GettyAbandoned buses, discontinued from active service, stand overgrown with creeper vines and other vegetation at a bus depot in Mumbai, India, on July 26, 2025.

Indranil Mukherjee / AFP / GettyAbandoned buses, discontinued from active service, stand overgrown with creeper vines and other vegetation at a bus depot in Mumbai, India, on July 26, 2025. Ma Weibing / Xinhua / GettyA view of the Great Wall on Taihang Mountains in Laiyuan County, in China’s Hebei province, on July 26, 2025

Ma Weibing / Xinhua / GettyA view of the Great Wall on Taihang Mountains in Laiyuan County, in China’s Hebei province, on July 26, 2025 Connie France / AFP / GettyRelatives of people killed during 2022–23 antigovernment protests, dressed in red, take part in a memorial ceremony at Cerro San Cristobal, in Lima, Peru, on July 27, 2025, on the eve of Peru's Independence Day. On January 9, 2023, protesters from the Puno Region joined nationwide demonstration that had erupted in December 2022, resulting in the death of 18 people during clashes with the police in the highland city of Juliaca.

Connie France / AFP / GettyRelatives of people killed during 2022–23 antigovernment protests, dressed in red, take part in a memorial ceremony at Cerro San Cristobal, in Lima, Peru, on July 27, 2025, on the eve of Peru's Independence Day. On January 9, 2023, protesters from the Puno Region joined nationwide demonstration that had erupted in December 2022, resulting in the death of 18 people during clashes with the police in the highland city of Juliaca. Liu Chaofu / VCG / GettyTourists enjoy the scenery at a large patch of lotus flowers and green leaves at a national wetland park in Qianxinan Buyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, Guizhou province, China, on July 26, 2025.

Liu Chaofu / VCG / GettyTourists enjoy the scenery at a large patch of lotus flowers and green leaves at a national wetland park in Qianxinan Buyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, Guizhou province, China, on July 26, 2025. Bernd Weißbrod / DPA / GettyA crane lifts a car from the scene of an accident where a regional train derailed, in Riedlingen, Germany, on July 28, 2025.

Bernd Weißbrod / DPA / GettyA crane lifts a car from the scene of an accident where a regional train derailed, in Riedlingen, Germany, on July 28, 2025. Sina Schuldt / DPA / GettyCar trains are parked at the marshaling yard in Bremen's Gröpelingen district, in Germany, on July 28, 2025.

Sina Schuldt / DPA / GettyCar trains are parked at the marshaling yard in Bremen's Gröpelingen district, in Germany, on July 28, 2025. Zhu Haiwei / Zhejiang Daily Press Group / VCG via Getty / VCGWorkers repair fishing nets in preparation for the upcoming fishing season, in Taizhou City, Zhejiang province, China, on July 27, 2025.

Zhu Haiwei / Zhejiang Daily Press Group / VCG via Getty / VCGWorkers repair fishing nets in preparation for the upcoming fishing season, in Taizhou City, Zhejiang province, China, on July 27, 2025. Tim de Waele / GettyDuring Stage 5 of the fourth Tour de France Femmes, the peloton passes through a flowery landscape, in Gueret, France, on July 30, 2025.

Tim de Waele / GettyDuring Stage 5 of the fourth Tour de France Femmes, the peloton passes through a flowery landscape, in Gueret, France, on July 30, 2025. Avishek Das / SOPA Images / LightRocket / GettyFarmers take part in a traditional rural-cattle race known as Moichara, ahead of the harvesting season, in Canning, India, on July 27, 2025.

Avishek Das / SOPA Images / LightRocket / GettyFarmers take part in a traditional rural-cattle race known as Moichara, ahead of the harvesting season, in Canning, India, on July 27, 2025. Liu Hongda / Xinhua / GettyPeople visit the Hukou Waterfall, on the Yellow River in Jixian County, in China’s Shanxi province, on July 27, 2025.

Liu Hongda / Xinhua / GettyPeople visit the Hukou Waterfall, on the Yellow River in Jixian County, in China’s Shanxi province, on July 27, 2025. Francois-Xavier Marit / AFP / GettyChen Yuxi, a diver with Team China, competes in the semi-final of the women’s 10-meter platform-diving event during the 2025 World Aquatics Championships, in Singapore, on July 31, 2025.

Francois-Xavier Marit / AFP / GettyChen Yuxi, a diver with Team China, competes in the semi-final of the women’s 10-meter platform-diving event during the 2025 World Aquatics Championships, in Singapore, on July 31, 2025. Khaled Desouki / AFP / GettyBoys cool down in a portable swimming pool in the al-Duwaiqa neighborhood of Cairo, Egypt, on July 29, 2025.

Khaled Desouki / AFP / GettyBoys cool down in a portable swimming pool in the al-Duwaiqa neighborhood of Cairo, Egypt, on July 29, 2025. Zhao Wenyu / China News Service / VCG / GettyFlood-affected villagers are transferred to a safe site in a plastic basin, at Liulimiao Town, Huairou District, Beijing, China, on July 28, 2025.

Zhao Wenyu / China News Service / VCG / GettyFlood-affected villagers are transferred to a safe site in a plastic basin, at Liulimiao Town, Huairou District, Beijing, China, on July 28, 2025. Mustafa Bikec / Anadolu / GettyEfforts to bring a forest fire under control continue in the Orhaneli district of Bursa, Turkey, as the blaze enters its third day, on July 28, 2025.

Mustafa Bikec / Anadolu / GettyEfforts to bring a forest fire under control continue in the Orhaneli district of Bursa, Turkey, as the blaze enters its third day, on July 28, 2025. Scott Peterson / GettyUkrainian firefighters battle a food-warehouse blaze that two Russian missiles caused in a strike that killed one security guard, on July 30, 2025, in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Russia has intensified missile and drone attacks against Ukraine, firing more than 700 in a single night and generally against civilian targets, amid a surge of daily aerial bombardments of urban centers, 3 and a half years since Russia invaded Ukraine.

Scott Peterson / GettyUkrainian firefighters battle a food-warehouse blaze that two Russian missiles caused in a strike that killed one security guard, on July 30, 2025, in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Russia has intensified missile and drone attacks against Ukraine, firing more than 700 in a single night and generally against civilian targets, amid a surge of daily aerial bombardments of urban centers, 3 and a half years since Russia invaded Ukraine. Abdel Kareem Hana / APHumanitarian aid is airdropped to Palestinians over the central Gaza Strip, pictured from Khan Younis, on July 28, 2025.

Abdel Kareem Hana / APHumanitarian aid is airdropped to Palestinians over the central Gaza Strip, pictured from Khan Younis, on July 28, 2025. Chung Sung-Jun / GettyChildren play in a water fountain on a hot day, in Seoul, South Korea, on July 25, 2025.

Chung Sung-Jun / GettyChildren play in a water fountain on a hot day, in Seoul, South Korea, on July 25, 2025. Eugene Hoshiko / APParticipants carry a portable shrine, or mikoshi, into the sea during a purification rite at the annual Kurihama Sumiyoshi Shrine Festival, in Yokosuka, Japan, on July 27, 2025.

Eugene Hoshiko / APParticipants carry a portable shrine, or mikoshi, into the sea during a purification rite at the annual Kurihama Sumiyoshi Shrine Festival, in Yokosuka, Japan, on July 27, 2025. Buddhika Weerasinghe / GettyA worker moves a large ice block at the Honda Reizo Company factory in Taishi, Japan, on July 28, 2025. As scorching temperatures persist across Japan, ice production is in full swing. Honda Reizo’s factory produces 113 tons of ice cubes daily to help people beat the summer heat.

Buddhika Weerasinghe / GettyA worker moves a large ice block at the Honda Reizo Company factory in Taishi, Japan, on July 28, 2025. As scorching temperatures persist across Japan, ice production is in full swing. Honda Reizo’s factory produces 113 tons of ice cubes daily to help people beat the summer heat. AFP / GettyPeople watch humanoid robots box at an exhibition during the World Artificial Intelligence Conference, in Shanghai, China, on July 26, 2025.

AFP / GettyPeople watch humanoid robots box at an exhibition during the World Artificial Intelligence Conference, in Shanghai, China, on July 26, 2025. Illustration by The Atlantic. Source: Getty.

Illustration by The Atlantic. Source: Getty. Ng Han Guan / AP

Ng Han Guan / AP Ng Han Guan / APTimo Barthel of Germany competes in the men’s 3m springboard-diving preliminaries at the World Aquatics Championships in Singapore on July 31, 2025.

Ng Han Guan / APTimo Barthel of Germany competes in the men’s 3m springboard-diving preliminaries at the World Aquatics Championships in Singapore on July 31, 2025. Vincent Thian / APGreece's Dimitrios Skoumpakis attempts a shot at goal during the men’s water-polo semifinal at the World Aquatics Championships in Singapore on July 22, 2025.

Vincent Thian / APGreece's Dimitrios Skoumpakis attempts a shot at goal during the men’s water-polo semifinal at the World Aquatics Championships in Singapore on July 22, 2025. Edgar Su / ReutersOpen-water swimmers dive into the water at the start of the mixed 4x1500m race at Sentosa Island, Singapore, on July 20, 2025.

Edgar Su / ReutersOpen-water swimmers dive into the water at the start of the mixed 4x1500m race at Sentosa Island, Singapore, on July 20, 2025. Marko Djurica / ReutersSwitzerland’s Jean-David Duval dives during the men’s 27m high-dive semifinals on Sentosa Island on July 25, 2025.

Marko Djurica / ReutersSwitzerland’s Jean-David Duval dives during the men’s 27m high-dive semifinals on Sentosa Island on July 25, 2025. Hollie Adams / ReutersCanada’s Kylie Masse swims in the women’s 50m backstroke semifinals on July 30, 2025.

Hollie Adams / ReutersCanada’s Kylie Masse swims in the women’s 50m backstroke semifinals on July 30, 2025. Maddie Meyer / GettyHannes Daube of Team United States and Lorenzo Bruni of Team Italy wrestle in the Classification 7th–8th Place match for men’s water polo on day 14 of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships.

Maddie Meyer / GettyHannes Daube of Team United States and Lorenzo Bruni of Team Italy wrestle in the Classification 7th–8th Place match for men’s water polo on day 14 of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships. Adam Pretty / GettyTeam China competes in the Team Technical Preliminaries on day 11 of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships on July 21, 2025.

Adam Pretty / GettyTeam China competes in the Team Technical Preliminaries on day 11 of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships on July 21, 2025. Lee Jin-man / APZoi Karangelou of Greece competes in the Women’s Solo Free preliminary of artistic swimming on July 20, 2025.

Lee Jin-man / APZoi Karangelou of Greece competes in the Women’s Solo Free preliminary of artistic swimming on July 20, 2025. Adam Pretty / GettyGold medalists Mayya Gurbanberdieva and Aleksandr Maltsev of Team Neutral Athletes B pose on the podium during the Mixed Duet Technical Final medal ceremony on July 23, 2025.

Adam Pretty / GettyGold medalists Mayya Gurbanberdieva and Aleksandr Maltsev of Team Neutral Athletes B pose on the podium during the Mixed Duet Technical Final medal ceremony on July 23, 2025. Adam Pretty / GettyShu Ohkubo and Rikuto Tamai of Team Japan compete in the men’s 10m synchronized-diving final on Day 19.

Adam Pretty / GettyShu Ohkubo and Rikuto Tamai of Team Japan compete in the men’s 10m synchronized-diving final on Day 19. Adam Pretty / GettyTeam Croatia gets into position prior to a preliminary-round match against Team Montenegro in men’s water polo at the OCBC Aquatic Center on July 14, 2025.

Adam Pretty / GettyTeam Croatia gets into position prior to a preliminary-round match against Team Montenegro in men’s water polo at the OCBC Aquatic Center on July 14, 2025. Francois-Xavier Marit / AFP / GettyTeam Neutral Athletes competes in the final of the Team Free artistic-swimming event on July 20, 2025.

Francois-Xavier Marit / AFP / GettyTeam Neutral Athletes competes in the final of the Team Free artistic-swimming event on July 20, 2025. Yong Teck Lim / GettyNicholas Sloman of Team Australia warms up ahead of the men’s 3km knockout sprint heat on day nine of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships.

Yong Teck Lim / GettyNicholas Sloman of Team Australia warms up ahead of the men’s 3km knockout sprint heat on day nine of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships. Oli Scarff / AFP / GettyThe Canadian swimmer Summer McIntosh reacts after competing in a semifinal of the women's 200m butterfly on July 30, 2025.

Oli Scarff / AFP / GettyThe Canadian swimmer Summer McIntosh reacts after competing in a semifinal of the women's 200m butterfly on July 30, 2025. Adam Pretty / GettyTeam Japan competes in the Team Technical Final on day 12, at the World Aquatics Championships Arena in Singapore.

Adam Pretty / GettyTeam Japan competes in the Team Technical Final on day 12, at the World Aquatics Championships Arena in Singapore. Yong Teck Lim / GettyTeam Spain competes in the Team Free Final on day 10.

Yong Teck Lim / GettyTeam Spain competes in the Team Free Final on day 10. Vincent Thian / APKatie Ledecky of the United States celebrates after winning the gold medal in the women’s 1500m freestyle final on July 29, 2025.

Vincent Thian / APKatie Ledecky of the United States celebrates after winning the gold medal in the women’s 1500m freestyle final on July 29, 2025. Ng Han Guan / APGabriela Agundez Garcia and Alejandra Estudillo Torres of Mexico compete in the women’s 10m synchronized-diving preliminaries on July 28, 2025.

Ng Han Guan / APGabriela Agundez Garcia and Alejandra Estudillo Torres of Mexico compete in the women’s 10m synchronized-diving preliminaries on July 28, 2025. Sarah Stier / GettyOsmar Olvera Ibarra of Team Mexico reacts after a dive during the men’s 3m springboard preliminaries on day 21.

Sarah Stier / GettyOsmar Olvera Ibarra of Team Mexico reacts after a dive during the men’s 3m springboard preliminaries on day 21. Manan Vatsyayana / AFP / GettyThe Team USA swimmer Kate Douglass competes in the final of the women’s 100m breaststroke on July 29, 2025.

Manan Vatsyayana / AFP / GettyThe Team USA swimmer Kate Douglass competes in the final of the women’s 100m breaststroke on July 29, 2025. Sarah Stier / GettyMelvin Imoudu of Team Germany competes in the men’s 50m breaststroke heats on day 19.

Sarah Stier / GettyMelvin Imoudu of Team Germany competes in the men’s 50m breaststroke heats on day 19. Francois-Xavier Marit / AFP / GettyThe Team China divers Cheng Zilong and Zhu Zifeng compete in the final of the men’s 10m platform synchronized-diving event on July 29, 2025.

Francois-Xavier Marit / AFP / GettyThe Team China divers Cheng Zilong and Zhu Zifeng compete in the final of the men’s 10m platform synchronized-diving event on July 29, 2025. Maye-E Wong / ReutersTeam Spain performs during the Team Acrobatic Artistic Swimming Final at the Singapore 2025 World Aquatics Championships on July 25, 2025.

Maye-E Wong / ReutersTeam Spain performs during the Team Acrobatic Artistic Swimming Final at the Singapore 2025 World Aquatics Championships on July 25, 2025.