Illustration by Michael Houtz

The euthanasia conference was held at a Sheraton. Some 300 Canadian professionals, most of them clinicians, had arrived for the annual event. There were lunch buffets and complimentary tote bags; attendees could look forward to a Friday-night social outing, with a DJ, at an event space above Par-Tee Putt in downtown Vancouver. “The most important thing,” one doctor told me, “is the networking.”

Which is to say that it might have been any other convention in Canada. Over the past decade, practitioners of euthanasia have become as familiar as orthodontists or plastic surgeons are with the mundane rituals of lanyards and drink tickets and It’s been so longs outside the ballroom of a four-star hotel. The difference is that, 10 years ago, what many of the attendees here do for work would have been considered homicide.

When Canada’s Parliament in 2016 legalized the practice of euthanasia—Medical Assistance in Dying, or MAID, as it’s formally called—it launched an open-ended medical experiment. One day, administering a lethal injection to a patient was against the law; the next, it was as legitimate as a tonsillectomy, but often with less of a wait. MAID now accounts for about one in 20 deaths in Canada—more than Alzheimer’s and diabetes combined—surpassing countries where assisted dying has been legal for far longer.

It is too soon to call euthanasia a lifestyle option in Canada, but from the outset it has proved a case study in momentum. MAID began as a practice limited to gravely ill patients who were already at the end of life. The law was then expanded to include people who were suffering from serious medical conditions but not facing imminent death. In two years, MAID will be made available to those suffering only from mental illness. Parliament has also recommended granting access to minors.

At the center of the world’s fastest-growing euthanasia regime is the concept of patient autonomy. Honoring a patient’s wishes is of course a core value in medicine. But here it has become paramount, allowing Canada’s MAID advocates to push for expansion in terms that brook no argument, refracted through the language of equality, access, and compassion. As Canada contends with ever-evolving claims on the right to die, the demand for euthanasia has begun to outstrip the capacity of clinicians to provide it.

There have been unintended consequences: Some Canadians who cannot afford to manage their illness have sought doctors to end their life. In certain situations, clinicians have faced impossible ethical dilemmas. At the same time, medical professionals who decided early on to reorient their career toward assisted death no longer feel compelled to tiptoe around the full, energetic extent of their devotion to MAID. Some clinicians in Canada have euthanized hundreds of patients.

The two-day conference in Vancouver was sponsored by a professional group called the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers. Stefanie Green, a physician on Vancouver Island and one of the organization’s founders, told me how her decades as a maternity doctor had helped equip her for this new chapter in her career. In both fields, she explained, she was guiding a patient through an “essentially natural event”—the emotional and medical choreography “of the most important days in their life.” She continued the analogy: “I thought, Well, one is like delivering life into the world, and the other feels like transitioning and delivering life out.” And so Green does not refer to her MAID deaths only as “provisions”—the term for euthanasia that most clinicians have adopted. She also calls them “deliveries.”

Gord Gubitz, a neurologist from Nova Scotia, told me that people often ask him about the “stress” and “trauma” and “strife” of his work as a MAID provider. Isn’t it so emotionally draining? In fact, for him it is just the opposite. He finds euthanasia to be “energizing”—the “most meaningful work” of his career. “It’s a happy sad, right?” he explained. “It’s really sad that you were in so much pain. It is sad that your family is racked with grief. But we’re so happy you got what you wanted.”

[From the June 2023 issue: David Brooks on how Canada’s assisted-suicide law went wrong]

Has Canada itself gotten what it wanted? Nine years after the legalization of assisted death, Canada’s leaders seem to regard MAID from a strange, almost anthropological remove: as if the future of euthanasia is no more within their control than the laws of physics; as if continued expansion is not a reality the government is choosing so much as conceding. This is the story of an ideology in motion, of what happens when a nation enshrines a right before reckoning with the totality of its logic. If autonomy in death is sacrosanct, is there anyone who shouldn’t be helped to die?

Rishad Usmani remembers the first patient he killed. She was 77 years old and a former Ice Capades skater, and she had severe spinal stenosis. Usmani, the woman’s family physician on Vancouver Island, had tried to talk her out of the decision to die. He would always do that, he told me, when patients first asked about medically assisted death, because often what he found was that people simply wanted to be comfortable, to have their pain controlled; that when they reckoned, really reckoned, with the finality of it all, they realized they didn’t actually want euthanasia. But this patient was sure: She was suffering, not just from the pain but from the pain medication too. She wanted to die.

On December 13, 2018, Usmani arrived at the woman’s home in the town of Comox, British Columbia. He was joined by a more senior physician, who would supervise the procedure, and a nurse, who would start the intravenous line. The patient lay in a hospital bed, her sister next to her, holding her hand. Usmani asked her a final time if she was sure; she said she was. He administered 10 milligrams of midazolam, a fast-acting sedative, then 40 milligrams of lidocaine to numb the vein in preparation for the 1,000 milligrams of propofol, which would induce a deep coma. Finally he injected 200 milligrams of a paralytic agent called rocuronium, which would bring an end to breathing, ultimately causing the heart to stop.

Usmani drew his stethoscope to the woman’s chest and listened. To his quiet alarm, he could hear the heart still beating. In fact, as the seconds passed, it seemed to be quickening. He glanced at his supervisor. Where had he messed up? But as soon as they locked eyes, he understood: He was listening to his own heartbeat.

Many clinicians in Canada who have provided medical assistance in dying have a story like this, about the tangle of nerves and uncertainties that attended their first case. Death itself is something every clinician knows intimately, the grief and pallor and paperwork of it. To work in medicine is to step each day into the worst days of other people’s lives. But approaching death as a procedure, as something to be scheduled over Outlook, took some getting used to. In Canada, it is no longer a novel and remarkable event. As of 2023, the last year for which data are available, some 60,300 Canadians had been legally helped to their death by clinicians. In Quebec, more than 7 percent of all deaths are by euthanasia—the highest rate of any jurisdiction in the world. “I have two or three provisions every week now, and it’s continuing to go up every year,” Claude Rivard, a family doctor in suburban Montreal, told me.

Rivard has thus far provided for more than 600 patients and helps train clinicians new to MAID. This spring, I watched from the back of a small classroom in a Vancouver hospital as Rivard led a workshop on intraosseous infusion—administering drugs directly into the bone marrow, a useful skill for MAID clinicians, Rivard explained, in the event of IV failure. Arranged on absorbent pads across the back row of tables were eight pig knuckles, bulbous and pink. After a PowerPoint presentation, the dozen or so attendees took turns with different injection devices, from the primitive (manual needles) to the modern (bone-injection guns). Hands cramped around hollow steel needles as the workshop attendees struggled to twist and drive the tools home. This was the last thing, the clinicians later agreed, that patients would want to see as they lay trying to die. Practitioners needed to learn. “Every detail matters,” Rivard told the class; he preferred the bone-injection gun himself.

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticClaude Rivard at his home near Montreal

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticClaude Rivard at his home near Montreal

The details of the assisted-death experience have become a preoccupation of Canadian life. Patients meticulously orchestrate their final moments, planning celebrations around them: weekend house parties before a Sunday-night euthanasia in the garden; a Catholic priest to deliver last rites; extended-family renditions of “Auld Lang Syne” at the bedside. For $10.99, you can design your MAID experience with the help of the Be Ceremonial app; suggested rituals include a story altar, a forgiveness ceremony, and the collecting of tears from witnesses. On the Disrupting Death podcast, hosted by an educator and a social worker in Ontario, guests share ideas on subjects such as normalizing the MAID process for children facing the death of an adult in their life—a pajama party at a funeral home; painting a coffin in a schoolyard.

Autonomy, choice, control: These are the values that found purchase with the great majority of Canadians in February 2015, when, in a case spearheaded by the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association, the supreme court of Canada unanimously overturned the country’s criminal ban on medically assisted death. For advocates, the victory had been decades in the making—the culmination of a campaign that had grown in fervor since the 1990s, when Canada’s high court narrowly ruled against physician-assisted death in a case brought by a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. “We’re talking about a competent person making a choice about their death,” one longtime right-to-die activist said while celebrating the new ruling. “Don’t access this choice if you don’t want—but stay away from my death bed.” A year later, in June 2016, Parliament passed the first legislation officially permitting medical assistance in dying for eligible adults, placing Canada among the handful of countries (including Belgium, Switzerland, and the Netherlands) and U.S. states (Oregon, Vermont, and California, among others) that already allowed some version of the practice.

[Read: How do I make sense of my mother’s decision to die?]

The new law approved medical assistance in dying for adults who had a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” causing them “intolerable suffering,” and who faced a “reasonably foreseeable” natural death. To qualify, patients needed two clinicians to sign off on their application, and the law required a 10-day “reflection period” before the procedure could take place. Patients could choose to die either by euthanasia—having a clinician administer the drugs directly—or, alternatively, by assisted suicide, in which a patient self-administers a lethal prescription orally. (Virtually all MAID deaths in Canada have been by euthanasia.) When the procedure was set to begin, patients were required to give final consent.

The law, in other words, was premised on the concept of patient autonomy, but within narrow boundaries. Rather than force someone with, say, late-stage cancer to suffer to the very end, MAID would allow patients to depart on their own terms: to experience a “dignified death,” as proponents called it. That the threshold of eligibility for MAID would be high—and stringent—was presented to the public as self-evident, although the criteria themselves were vague when you looked closely. For instance, what constituted “reasonably foreseeable”? Two months? Two years? Canada’s Department of Justice suggested only “a period of time that is not too remote.”

Provincial health authorities were left to fill in the blanks. Following the law’s passage, doctors, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and lawyers scrambled to draw up the regulatory fine print for a procedure that until then had been legally classified as culpable homicide. How should the assessment process work? What drugs should be used? Particularly vexing was the question of whether it should be clinicians or patients who initiated conversations about assisted death. Some argued that doctors and nurses had a professional obligation to broach the subject of MAID with potentially eligible patients, just as they would any other “treatment option.” Others feared that patients could interpret this as a recommendation—indeed, feared that talking about assisted death as a medical treatment, like Lasik surgery or a hip replacement, was dangerous in itself.

Early on, a number of health-care professionals refused to engage in any way with MAID—some because of religious beliefs, and others because, in their view, it violated a medical duty to “do no harm.” For many clinicians, the ethical and logistical challenges of MAID only compounded the stress of working within Canada’s public-health-care system, beset by years of funding cuts and staffing shortages. The median wait time for general surgery is about 22 weeks. For orthopedic surgery, it’s more than a year. For some kinds of mental-health services, the wait time can be longer.

As the first assessment requests trickled in, even many clinicians who believed strongly in the right to an assisted death were reluctant to do the actual assisting. Some told me they agreed to take on patients only after realizing that no one else—in their hospital or even their region—was willing to go first. Matt Kutcher, a physician on Prince Edward Island, was more open to MAID than others, but acknowledged the challenge of building the practice of assisted death virtually from scratch. “The reality,” he said, “is that we were all just kind of making it up as we went along, very cautiously.”

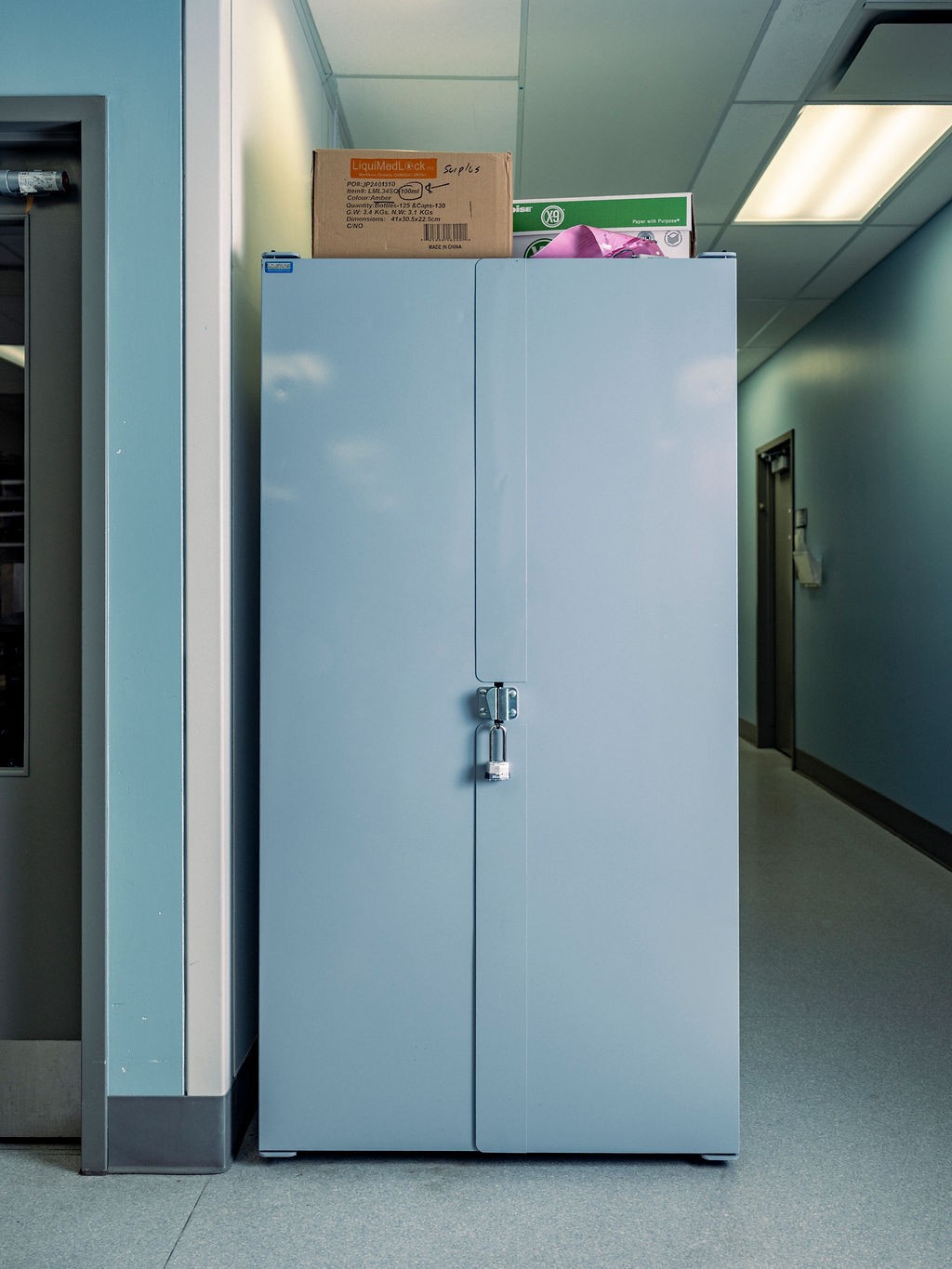

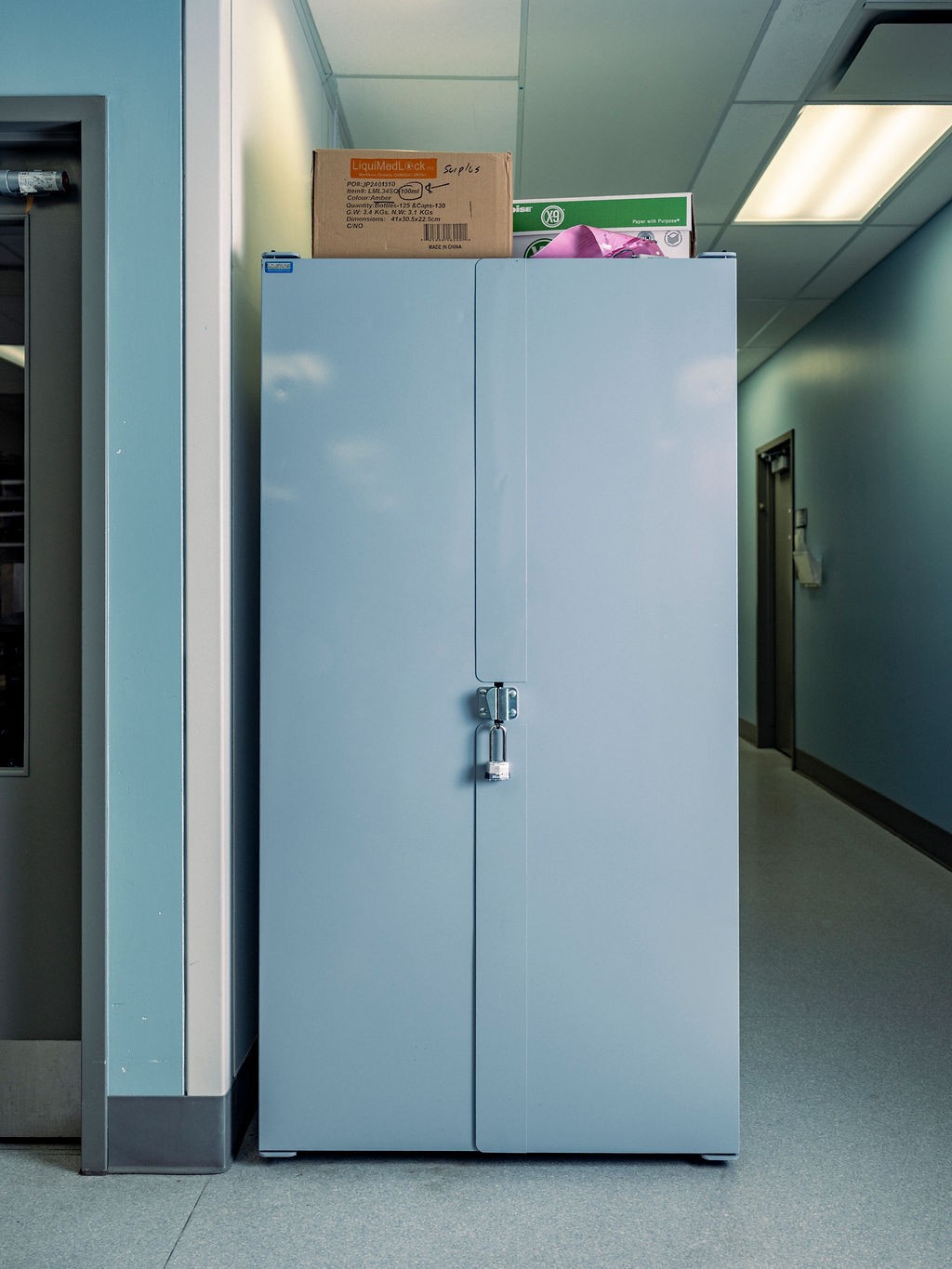

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticReady-to-use MAID kits in a hospital vault

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticReady-to-use MAID kits in a hospital vault

On a rainy spring evening in 2017, Kutcher drove to a farmhouse by the sea to administer the first state-sanctioned act of euthanasia in his province. The patient, Paul Couvrette, had learned about MAID from his wife, Liana Brittain, in 2015, soon after the supreme-court decision. He had just been diagnosed with lung cancer, and while processing this fact in the parking lot of the clinic had turned to his wife and announced: “I’m not going to have cancer. I’m going to kill myself.” Brittain told her husband this was a bit dramatic. “You know, dear, you don’t have to do that,” she recalls responding. “The government will do it for you, and they’ll do it for free.” Couvrette had marveled at the news, because although he was open to surgery, he had no interest in chemotherapy or radiation. MAID, Brittain told me, gave her husband the relief of a “back door.” By early 2017, the cancer had spread to Couvrette’s brain; the 72-year-old became largely bedridden. He set his MAID procedure for May 10—the couple’s wedding anniversary.

Kutcher and a nurse had agreed to come early and join the extended family—children, a granddaughter—for Couvrette’s final dinner: seafood chowder and gluten-free biscuits. Only Brittain would eventually join Couvrette in the downstairs bedroom; the rest of the family and the couple’s two dogs would wait outside on the beach. There was a shared understanding, Kutcher recalled, that “this was something none of us had experienced before, and we didn’t really know what we were in for.” What followed was a “beautiful death”—that was what the local newspaper called it, Brittain told me. Couvrette’s last words to his wife came from their wedding vows: I’ll love you forever, plus three days.

Kutcher wrestled at first with the sheer strangeness of the experience—how quickly it was over, packing up his equipment at the side of a dead man who just 10 minutes earlier had been talking with him, very much alive. But he went home believing he had done the right thing for his patient.

For proponents, Couvrette epitomized the ideal MAID candidate, motivated not by an impulsive death wish but by a considered desire to reclaim control of his fate from a terminal disease. The lobbying group Dying With Dignity Canada celebrated Couvrette’s “empowering choice and journey” as part of a showcase on its website of “good deaths” made possible by the new law. There was also the surgeon in Nova Scotia with Parkinson’s who “died the same way he lived—on his own terms.” And there were the Toronto couple in their 90s who, in a “dream ending to their storybook romance,” underwent MAID together.

Such heartfelt accounts tended to center on the white, educated, financially stable patients who represented the typical MAID recipient. The stories did not precisely capture what many clinicians were discovering also to be true: that if dying by MAID was dying with dignity, some deaths felt considerably more dignified than others. Not everyone has coastal homes or children and grandchildren who can gather in love and solidarity. This was made clear to Sandy Buchman, a palliative-care physician in Toronto, during one of his early MAID cases, when a patient, “all alone,” gave final consent from a mattress on the floor of a rental apartment. Buchman recalls having to kneel next to the mattress in the otherwise empty space to administer the drugs. “It was horrible,” he told me. “You can see how challenging, how awful, things can be.”

In 2018, Buchman co-founded a nonprofit organization called MAiDHouse. The aim was to create a “third place” of sorts for people who want to die somewhere other than a hospital or at home. Finding a location proved difficult; many landlords were resistant. But by 2022, MAiDHouse had leased the space in Toronto from which it operates today. (For security reasons, the location is not public.) Tekla Hendrickson, the executive director of MAiDHouse, told me the space was designed to feel warm and familiar but also adaptable to the wishes of the person using it: furniture light enough to rearrange, bare surfaces for flowers or photos or any other personal items. “Sometimes they have champagne, sometimes they come in limos, sometimes they wear ball gowns,” Hendrickson said. The act of euthanasia itself takes place in a La-Z-Boy-like recliner, with adjacent rooms available for family and friends who may prefer not to witness the procedure. According to the MAiDHouse website, the body is then transferred to a funeral home by attendants who arrive in unmarked cars and depart “discreetly.”

Since its founding, MAiDHouse has provided space and support for more than 100 deaths. The group’s homepage displays a photograph of dandelion seeds scattering in a gentle wind. A second MAiDHouse location recently opened in Victoria, British Columbia. In the organization’s 2023 annual report, the chair of the board noted that MAiDHouse’s followers on LinkedIn had increased by 85 percent; its new Instagram profile was gaining followers too. More to the point, the number of provisions performed at MAiDHouse had doubled over the previous year—“astounding progress for such a young organization.”

In the early days of MAID, some clinicians found themselves at once surprised and conflicted by the fulfillment they experienced in helping people die. A few months after the law’s passage, Stefanie Green, whom I’d met at the conference in Vancouver, acknowledged to herself how “upbeat” she’d felt following a recent provision—“a little hyped up on adrenaline,” as she later put it in a memoir about her first year providing medical assistance in death. Green realized it was gratification she was feeling: A patient had come to her in immense pain, and she had been in a position to offer relief. In the end, she believed, she had “given a gift to a dying man.”

Green had at first been reluctant to reveal her feelings to anyone, afraid that she might be viewed, she recalled, as a “psychopath.” But she did eventually confide in a small group of fellow MAID practitioners. Green and several colleagues realized that there was a need for a formal community of professionals. In 2017, they officially launched the group whose meeting I attended.

There was a time when Madeline Li would have felt perfectly at home among the other clinicians who convened that weekend at the Sheraton. In the early years of MAID, few physicians exerted more influence over the new regime than Li. The Toronto-based cancer psychiatrist led the development of the MAID program at the University Health Network, the largest teaching-hospital system in Canada, and in 2017 saw her framework published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Tony Luong for The AtlanticMadeline Li at her office in Toronto

Tony Luong for The AtlanticMadeline Li at her office in Toronto

It was not long into her practice, however, that Li’s confidence in the direction of her country’s MAID program began to falter. For all of her expertise, not even Li was sure what to do about a patient in his 30s whom she encountered in 2018.

The man had gone to the emergency room complaining of excruciating pain and was eventually diagnosed with cancer. The prognosis was good, a surgeon assured him, with a 65 percent chance of a cure. But the man said he didn’t want treatment; he wanted MAID. Startled, the surgeon referred him to a medical oncologist to discuss chemo; perhaps the man just didn’t want surgery. The patient proceeded to tell the medical oncologist that he didn’t want treatment of any kind; he wanted MAID. He said the same thing to a radiation oncologist, a palliative-care physician, and a psychiatrist, before finally complaining to the patient-relations department that the hospital was barring his access to MAID. Li arranged to meet with him.

Canada’s MAID law defines a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” in part as a “serious and incurable illness, disease, or disability.” As for what constitutes incurability, however, the law says nothing—and of the various textual ambiguities that caused anxiety for clinicians early on, this one ranked near the top. Did “incurable” mean a lack of any available treatment? Did it mean the likelihood of an available treatment not working? Prominent MAID advocates put forth what soon became the predominant interpretation: A medical condition was incurable if it could not be cured by means acceptable to the patient.

This had made sense to Li. If an elderly woman with chronic myelogenous leukemia had no wish to endure a highly toxic course of chemo and radiation, why should she be compelled to? But here was a young man with a likely curable cancer who nevertheless was adamant about dying. “I mean, he was so, so clear,” Li told me. “I talked to him about What if you had a 100 percent chance? Would you want treatment? And he said no.” He didn’t want to suffer through the treatment or the side effects, he explained; just having a colonoscopy had traumatized him. When Li assured the man that they could treat the side effects, he said she wasn’t understanding him: Yes, they could give him medication for the pain, but then he would have to first experience the pain. He didn’t want to experience the pain.

What was Li left with? According to prevailing standards, the man’s refusal to attempt treatment rendered his disease incurable and his natural death was reasonably foreseeable. He met the eligibility criteria as Li understood them. But the whole thing seemed wrong to her. Seeking advice, she described the basics of the case in a private email group for MAID practitioners under the heading “Eligible, but Reasonable?” “And what was very clear to me from the replies I got,” Li told me, “is that many people have no ethical or clinical qualms about this—that it’s all about a patient’s autonomy, and if a patient wants this, it’s not up to us to judge. We should provide.”

And so she did. She regretted her decision almost as soon as the man’s heart stopped beating. “What I’ve learned since is: Eligible doesn’t mean you should provide MAID,” Li told me. “You can be eligible because the law is so full of holes, but that doesn’t mean it clinically makes sense.” Li no longer interprets “incurable” as at the sole discretion of the patient. The problem, she feels, is that the law permits such a wide spectrum of interpretations to begin with. Many decisions about life and death turn on the personal values of practitioners and patients rather than on any objective medical criteria.

By 2020, Li had overseen hundreds of MAID cases, about 95 percent of which were “very straightforward,” she said. They involved people who had terminal conditions and wanted the same control in death as they’d enjoyed in life. It was the 5 percent that worried her—not just the young man, but vulnerable people more generally, whom the safeguards had possibly failed. Patients whose only “terminal condition,” really, was age. Li recalled an especially divisive early case for her team involving an elderly woman who’d fractured her hip. She understood that the rest of her life would mean becoming only weaker and enduring more falls, and she “just wasn’t going to have it.” The woman was approved for MAID on the basis of frailty.

Li had tried to understand the assessor’s reasoning. According to an actuarial table, the woman, given her age and medical circumstances, had a life expectancy of five or six more years. But what if the woman had been slightly younger and the number was closer to eight years—would the clinician have approved her then? “And they said, well, they weren’t sure, and that’s my point,” Li explained. “There’s no standard here; it’s just kind of up to you.” The concept of a “completed life, or being tired of life,” as sufficient for MAID is “controversial in Europe and theoretically not legal in Canada,” Li said. “But the truth is, it is legal in Canada. It always has been, and it’s happening in these frailty cases.”

Li supports medical assistance in dying when appropriate. What troubles her is the federal government’s deferring of responsibility in managing it—establishing principles, setting standards, enforcing boundaries. She believes most physicians in Canada share her “muddy middle” position. But that position, she said, is also “the most silent.”

In 2014, when the question of medically assisted death had come before Canada’s supreme court, Etienne Montero, a civil-law professor and at the time the president of the European Institute of Bioethics, warned in testimony that the practice of euthanasia, once legal, was impossible to control. Montero had been retained by the attorney general of Canada to discuss the experience of assisted death in Belgium—how a regime that had begun with “extremely strict” criteria had steadily evolved, through loose interpretations and lax enforcement, to accommodate many of the very patients it had once pledged to protect. When a patient’s autonomy is paramount, Montero argued, expansion is inevitable: “Sooner or later, a patient’s repeated wish will take precedence over strict statutory conditions.” In the end, the Canadian justices were unmoved; Belgium’s “permissive” system, they contended, was the “product of a very different medico-legal culture” and therefore offered “little insight into how a Canadian regime might operate.” In a sense, this was correct: It took Belgium more than 20 years to reach an assisted-death rate of 3 percent. Canada needed only five.

In retrospect, the expansion of MAID would seem to have been inevitable; Justin Trudeau, then Canada’s prime minister, said as much back in 2016, when he called his country’s newly passed MAID law “a big first step” in what would be an “evolution.” Five years later, in March 2021, the government enacted a new two-track system of eligibility, relaxing existing safeguards and extending MAID to a broader swath of Canadians. Patients approved for an assisted death under Track 1, as it was now called—meaning the original end-of-life context—were no longer required to wait 10 days before receiving MAID; they could die on the day of approval. Track 2, meanwhile, legalized MAID for adults whose deaths were not reasonably foreseeable—people suffering from chronic pain, for example, or from certain neurological disorders. Although cost savings have never been mentioned as an explicit rationale for expansion, the parliamentary budget office anticipated annual savings in health-care costs of nearly $150 million as a result of the expanded MAID regime.

The 2021 law did provide for additional safeguards unique to Track 2. Assessors had to ensure that applicants gave “serious consideration”—a phrase left undefined—to “reasonable and available means” to alleviate their suffering. In addition, they had to affirm that the patients had been directed toward such options. Track 2 assessments were also required to span at least 90 days. For any MAID assessment, clinicians must be satisfied not only that a patient’s suffering is enduring and intolerable, but that it is a function of a physical medical condition rather than mental illness, say, or financial instability. Suffering is never perfectly reducible, of course—a crisp study in cause and effect. But when a patient is already dying, the role of physical disease isn’t usually a mystery, either.

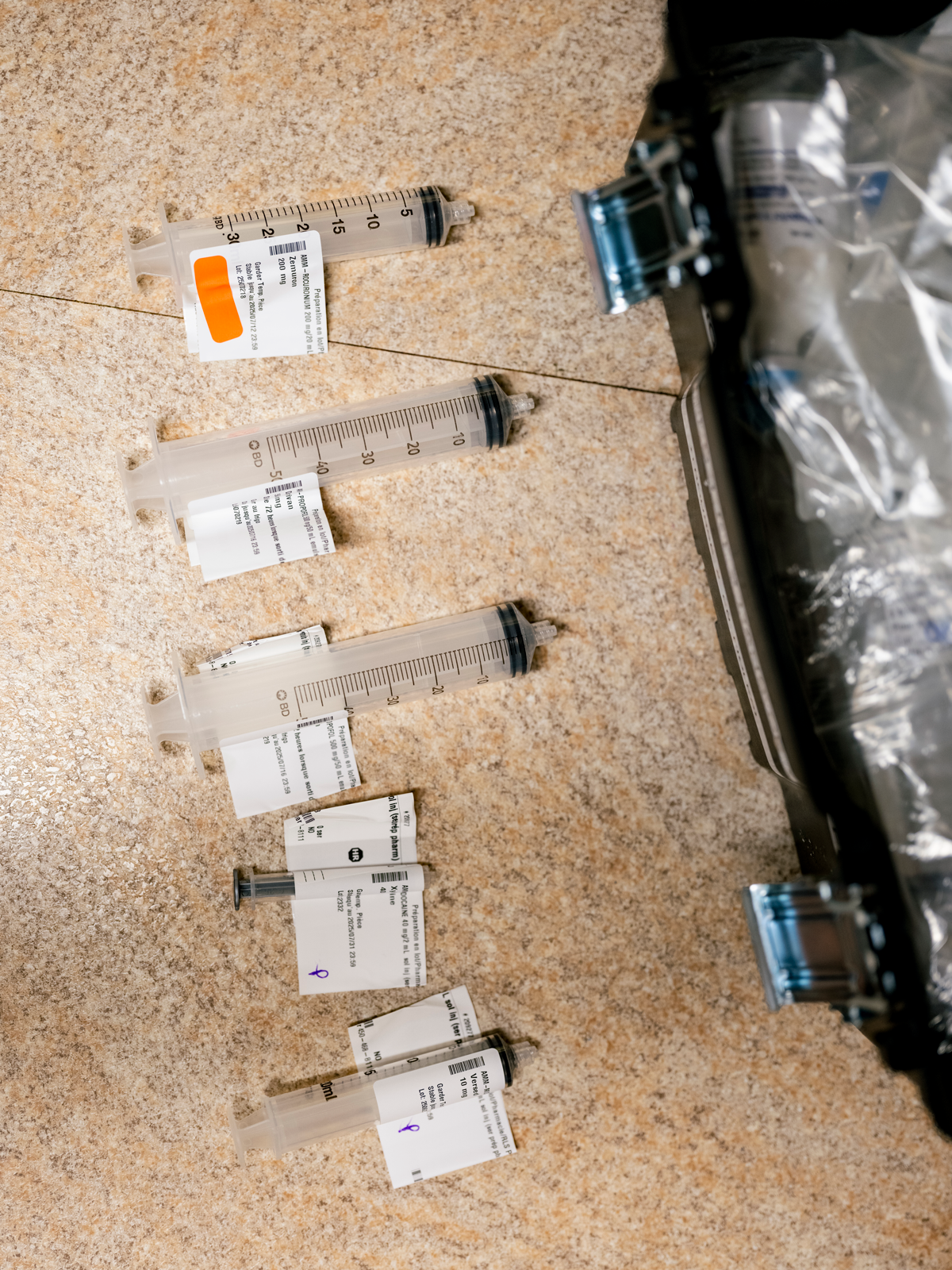

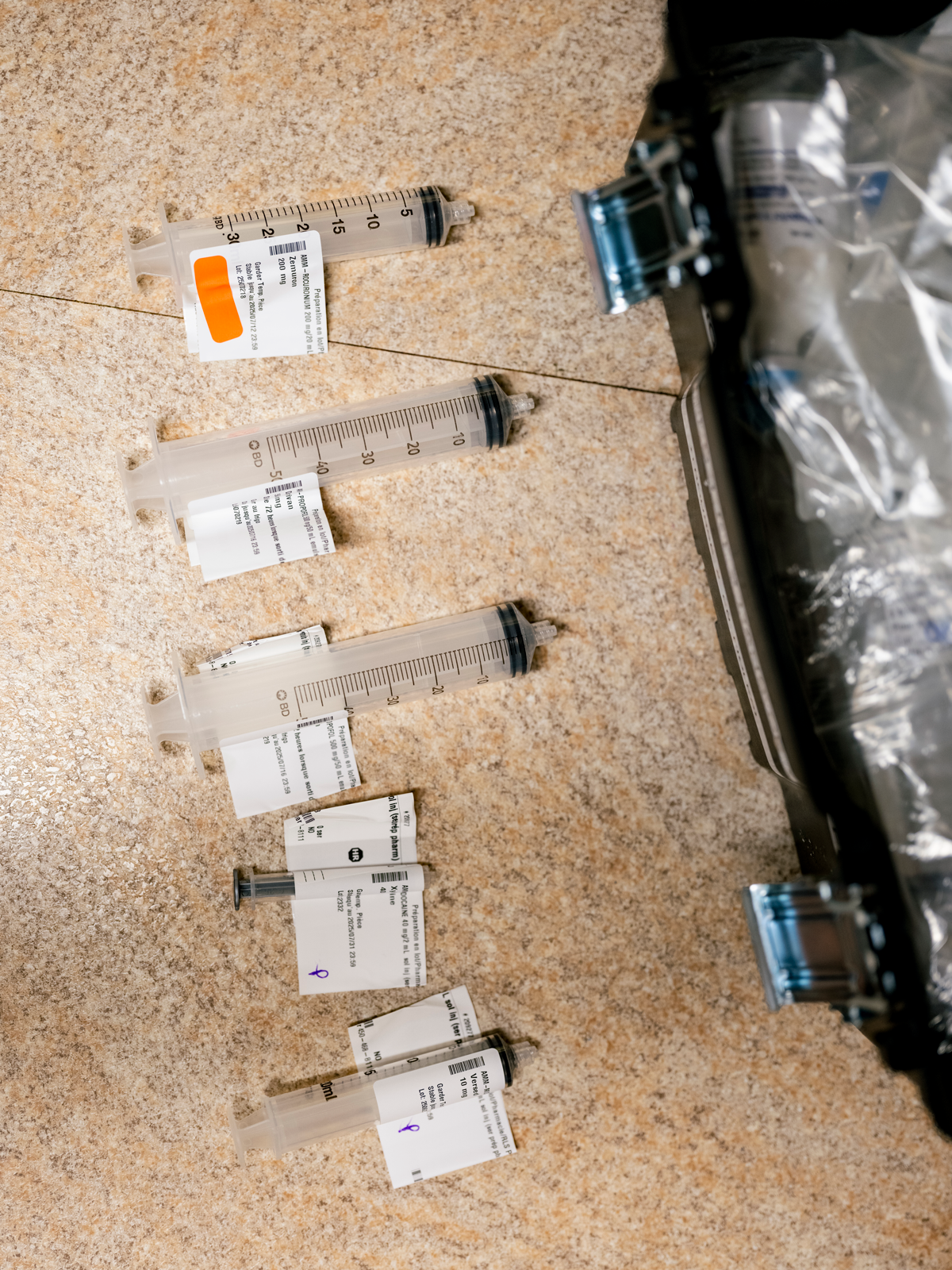

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticDepleted syringes after a MAID provision

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticDepleted syringes after a MAID provision

Track 2 introduced a web of moral complexities and clinical demands. For many practitioners, one major new factor was the sheer amount of time required to understand why the person before them—not terminally ill—was asking, at that particular moment, to die. Clinicians would have to untangle the physical experience of chronic illness and disability from the structural inequities and mental-health struggles that often attend it. In a system where access to social supports and medical services varies so widely, this was no small challenge, and many clinicians ultimately chose not to expand their practice to include Track 2 patients.

There is no clear official data on how many clinicians are willing to take on Track 2 cases. The government’s most recent information indicates that, in 2023, out of 2,200 MAID practitioners overall, a mere 89 were responsible for about 30 percent of all Track 2 provisions. Jonathan Reggler, a family physician on Vancouver Island, is among that small group. He openly acknowledges the challenges involved in assessing Track 2 patients, as well as the basic “discomfort” that comes with ending the life of someone who is not in fact dying. “I can think of cases that I’ve dealt with where you’re really asking yourself, Why?” he told me. “Why now? Why is it that this cluster of problems is causing you such distress where another person wouldn’t be distressed?”

Yet Reggler feels duty bound to move beyond his personal discomfort. As he explained it, “Once you accept that people ought to have autonomy—once you accept that life is not sacred and something that can only be taken by God, a being I don’t believe in—then, if you’re in that work, some of us have to go forward and say, ‘We’ll do it.’ ”

For some MAID practitioners, however, it took encountering an eligible patient for them to realize the true extent of their unease with Track 2. One physician, who requested anonymity because he was not authorized by his hospital to speak publicly, recalled assessing a patient in their 30s with nerve damage. The pain was such that they couldn’t go outside; even the touch of a breeze would inflame it. “They had seen every kind of specialist,” he said. The patient had tried nontraditional therapies too—acupuncture, Reiki, “everything.” As the physician saw it, the patient’s condition was serious and incurable, it was causing intolerable suffering, and the suffering could not seem to be relieved. “I went through all of the tick boxes, and by the letter of the law, they clearly met the criteria for all of these things, right? That said, I felt a little bit queasy.” The patient was young, with a condition that is not terminal and is usually treatable. But “I didn’t feel it was my place to tell them no.”

He was not comfortable doing the procedure himself, however. He recalled telling the MAID office in his region, “Look, I did the assessment. The patient meets the criteria. But I just can’t—I can’t do this.” Another clinician stepped in.

In 2023, Track 2 accounted for 622 MAID deaths in Canada—just over 4 percent of cases, up from 3.5 percent in 2022. Whether the proportion continues to rise is anyone’s guess. Some argue that primary-care providers are best positioned to negotiate the complexities of Track 2 cases, given their familiarity with the patient making the request—their family situation, medical history, social circumstances. This is how assisted death is typically approached in other countries, including Belgium and the Netherlands. But in Canada, the system largely developed around the MAID coordination centers assembled in the provinces, complete with 1-800 numbers for self-referrals. The result is that MAID assessors generally have no preexisting relationship with the patients they’re assessing.

How do you navigate, then, the hidden corridors of a stranger’s suffering? Claude Rivard told me about a Track 2 patient who had called to cancel his scheduled euthanasia. As a result of a motorcycle accident, the man could not walk; now blind, he was living in a long-term-care facility and rarely had visitors; he had been persistent in his request for MAID. But when his family learned that he’d applied and been approved, they started visiting him again. “And it changed everything,” Rivard said. He was in contact with his children again. He was in contact with his ex-wife again. “He decided, ‘No, I still have pleasure in life, because the family, the kids are coming; even if I can’t see them, I can touch them, and I can talk to them, so I’m changing my mind.’ ”

I asked Rivard whether this turn of events—the apparent plasticity of the man’s desire to die—had given him pause about approving the patient for MAID in the first place. Not at all, he said. “I had no control on what the family was going to do.”

Some of the opposition to MAID in Canada is religious in character. The Catholic Church condemns euthanasia, though Church influence in Canada, as elsewhere, has waned dramatically, particularly where it was once strongest, in Quebec. But from the outset there were other concerns, chief among them the worry that assisted death, originally authorized for one class of patient, would eventually become legal for a great many others too. National disability-rights groups warned that Canadians with physical and intellectual disabilities—people whose lives were already undervalued in society, and of whom 17 percent live in poverty—would be at particular risk. As assisted death became “sanitized,” one group argued, “more and more will be encouraged to choose this option, further entrenching the ‘better off dead’ message in public consciousness.”

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticAt a hospital in Quebec, a pharmacist prepares the drugs used in euthanasia.

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticAt a hospital in Quebec, a pharmacist prepares the drugs used in euthanasia.

For these critics, the “reasonably foreseeable” death requirement had been the solitary consolation in an otherwise lost constitutional battle. The elimination of that protection with the creation of Track 2 reinforced their conviction that MAID would result in Canada’s most marginalized citizens being subtly coerced into premature death. Canadian officials acknowledged these concerns—“We know that in some places in our country, it’s easier to access MAID than it is to get a wheelchair,” Carla Qualtrough, the disability-inclusion minister, admitted in 2020—but reiterated that socioeconomic suffering was not a legal basis for MAID. Justin Trudeau took pains to assure the public that patients were not being backed into assisted death because of their inability to afford proper housing, say, or get timely access to medical care. It “simply isn’t something that ends up happening,” he said.

Sathya Dhara Kovac, of Winnipeg, knew otherwise. Before dying by MAID in 2022, at the age of 44, Kovac wrote her own obituary. She explained that life with ALS had “not been easy”; it was, as far as illnesses went, a “shitty” one. But the illness itself was not the reason she wanted to die. Kovac told the local press prior to being euthanized that she had fought unsuccessfully to get adequate home-care services; she needed more than the 55 hours a week covered by the province, couldn’t afford the cost of a private agency to take care of the balance, and didn’t want to be relegated to a long-term-care facility. “Ultimately it was not a genetic disease that took me out, it was a system,” Kovac wrote. “I could have had more time if I had more help.”

Earlier this spring, I met in Vancouver with Marcia Doherty; she was approved for Track 2 MAID shortly after it was legalized, four years ago. The 57-year-old has suffered for most of her life from complex chronic illnesses, including myalgic encephalomyelitis, fibromyalgia, and Epstein-Barr virus. Her daily experience of pain is so total that it is best captured in terms of what doesn’t hurt (the tips of her ears; sometimes the tip of her nose) as opposed to all the places that do. Yet at the core of her suffering is not only the pain itself, Doherty told me; it’s that, as the years go by, she can’t afford the cost of managing it. Only a fraction of the treatments she relies on are covered by her province’s health-care plan, and with monthly disability assistance her only consistent income, she is overwhelmed with medical debt. Doherty understands that someday, the pressure may simply become too much. “I didn’t apply for MAID because I want to be dead,” she told me. “I applied for MAID on ruthless practicality.”

It is difficult to understand MAID in such circumstances as a triumphant act of autonomy—as if the state, by facilitating death where it has failed to provide adequate resources to live, has somehow given its most vulnerable citizens the dignity of choice. In January 2024, a quadriplegic man named Normand Meunier entered a Quebec hospital with a respiratory infection; after four days confined to an emergency-room stretcher, unable to secure a proper mattress despite his partner’s pleas, he developed a painful bedsore that led him to apply for MAID. “I don’t want to be a burden,” he told Radio-Canada the day before he was euthanized, that March.

[Read: Brittany Maynard and the challenge of dying with dignity]

Nearly half of all Canadians who have died by MAID viewed themselves as a burden on family and friends. For some disabled citizens, the availability of assisted death has sowed doubt about how the medical establishment itself sees them—about whether their lives are in fact considered worthy of saving. In the fall of 2022, a 49-year-old Nova Scotia woman who is physically disabled and had recently been diagnosed with breast cancer was readying for a lifesaving mastectomy when a member of her surgical team began working through a list of pre-op questions about her medications and the last time she ate—and was she familiar with medical assistance in dying? The woman told me she felt suddenly and acutely aware of her body, the tissue-thin gown that wouldn’t close. “It left me feeling like maybe I should be second-guessing my decision,” she recalled. “It was the thing I was thinking about as I went under; when I woke up, it was the first thought in my head.” Fifteen months later, when the woman returned for a second mastectomy, she was again asked if she was aware of MAID. Today she still wonders if, were she not disabled, the question would even have been asked. Gus Grant, the registrar and CEO of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia, has said that the timing of the queries to this woman was “clearly inappropriate and insensitive,” but he also emphasized that “there’s a difference between raising the topic of discussing awareness about MAID, and possible eligibility, from offering MAID.”

And yet there is also a reason why, in some countries, clinicians are either expressly prohibited or generally discouraged from initiating conversations about assisted death. However sensitively the subject is broached, death never presents itself neutrally; to regard the line between an “offer” and a simple recitation of information as somehow self-evident is to ignore this fact, as well as the power imbalance that freights a health professional’s every gesture with profound meaning. Perhaps the now-suspended Veterans Affairs caseworker who, in 2022, was found by the department to have “inappropriately raised” MAID with several service members had meant no harm. But according to testimony, one combat veteran was so shaken by the exchange—he had called seeking support for his ailments and was not suicidal, but was told that MAID was preferable to “blowing your brains out”—that he left the country.

[Content truncated due to length...]

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticClaude Rivard at his home near Montreal

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticClaude Rivard at his home near Montreal

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticReady-to-use MAID kits in a hospital vault

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticReady-to-use MAID kits in a hospital vault Tony Luong for The AtlanticMadeline Li at her office in Toronto

Tony Luong for The AtlanticMadeline Li at her office in Toronto Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticDepleted syringes after a MAID provision

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticDepleted syringes after a MAID provision Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticAt a hospital in Quebec, a pharmacist prepares the drugs used in euthanasia.

Johnny C. Y. Lam for The AtlanticAt a hospital in Quebec, a pharmacist prepares the drugs used in euthanasia. Still Life With Fruits and Insects (1710) (Johnny Van Haeften / Bridgeman Images)

Still Life With Fruits and Insects (1710) (Johnny Van Haeften / Bridgeman Images) Posy of Flowers, With a Tulip and a Melon, on a Stone Ledge (1748) (Bridgeman Images)

Posy of Flowers, With a Tulip and a Melon, on a Stone Ledge (1748) (Bridgeman Images) Illustration by Matteo Giuseppe Pani

Illustration by Matteo Giuseppe Pani Curiosity used its mast camera to capture this mosaic of Gediz Vallis on November 7, 2022, its 3,646th Martian day. (NASA)

Curiosity used its mast camera to capture this mosaic of Gediz Vallis on November 7, 2022, its 3,646th Martian day. (NASA) Courtesy of Belinda J. Kein

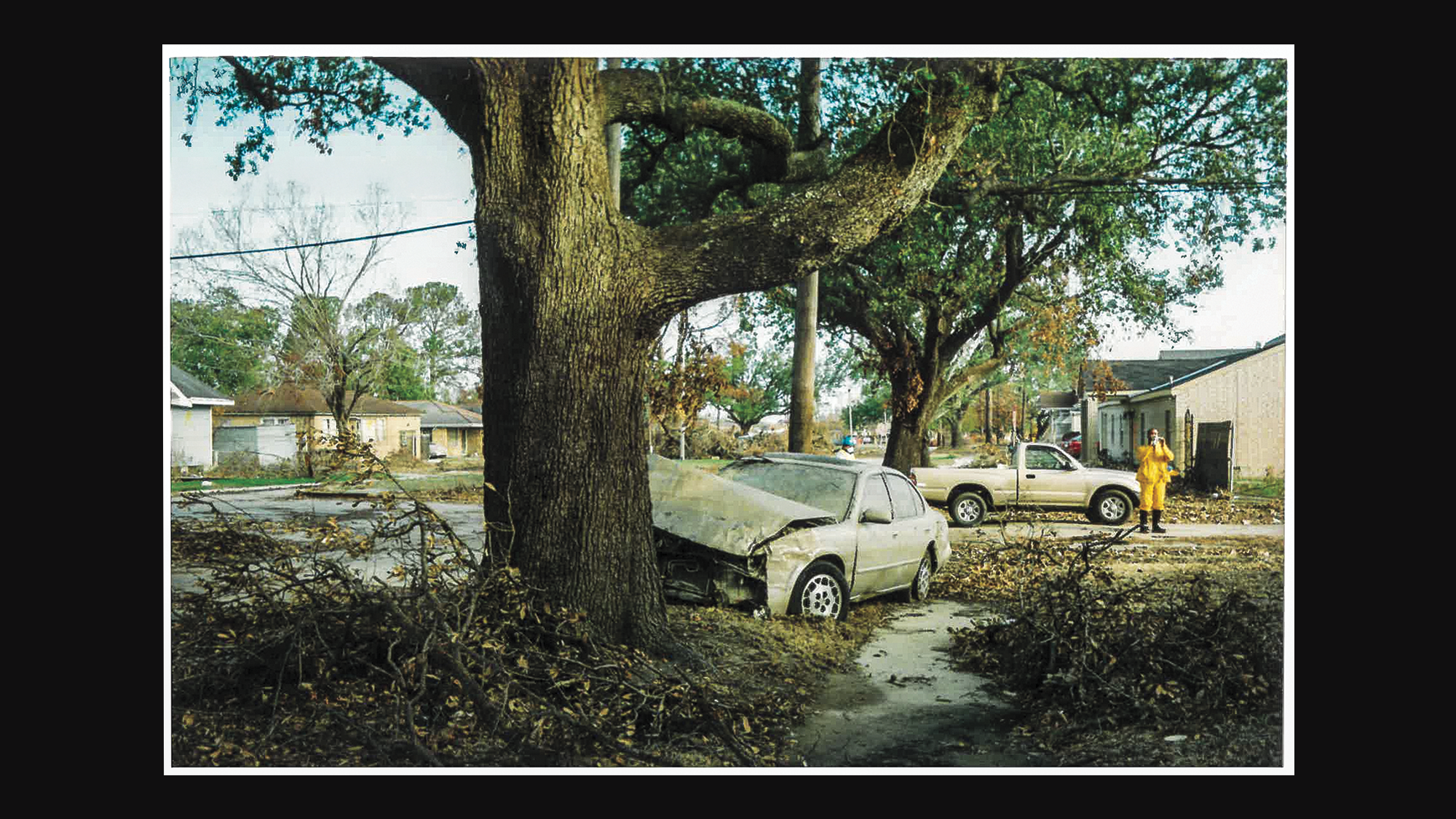

Courtesy of Belinda J. Kein When Clint Smith and his family returned to their New Orleans home in October 2005, they found a house, and a neighborhood, destroyed by flooding. Courtesy of Clint Smith

When Clint Smith and his family returned to their New Orleans home in October 2005, they found a house, and a neighborhood, destroyed by flooding. Courtesy of Clint Smith Eakin Howard / AP

Eakin Howard / AP