Subscribe here: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Overcast | Pocket Casts

A week ago, President Donald Trump signed an executive order called “Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets.” The order states that “vagrancy” and “violent attacks have made our cities unsafe” and encourages the expanded use of institutionalization.

The order comes at a crucial moment for many American cities that have tried—and often failed—to meaningfully address homelessness and addiction. In 2024, the number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night was 771,480, the highest number ever recorded in the United States.

In recent years, San Francisco has become emblematic of the crisis. And now a new mayor has pledged to prioritize the problem. To understand what’s at stake, I got to know one man who has been living on the street and struggling with addiction—and who says he is finally ready to make a change.

This is the first episode of a new three-part miniseries from Radio Atlantic, No Easy Fix, about what it takes to escape one’s demons.

The following is a transcript of the episode:

Hanna Rosin: A week ago, President Trump signed an executive order called “Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets.”

Now, this order could be read as Trump setting up another showdown between his administration and liberal cities. But actually, some cities are already ahead of him on this.

I’m Hanna Rosin. This is Radio Atlantic. Over the next three weeks, we’re bringing you a special series about the beginnings of an experiment.

A lot of American cities already know they have a real problem: a few streets or a neighborhood where the social order seems to have completely broken down. They’re crowded with people living on the streets, often with addiction. And even before this executive order was signed, some cities were beginning to take these places on—or at least audition some new ways to fix the problem.

Reporter Ethan Brooks looks at San Francisco, which is an obvious place to look because it’s a city known for being exceptional at thinking up solutions to all kinds of complicated problems.

Why hasn’t it been able to crack this one? Ethan finds some answers close to the ground. He follows one guy and gets some insights about why the solution these cities are looking for is so elusive.

Evan: I know some people that will spend hours and hours and hours and hours just holding up a cardboard sign in an intersection. It might take him 10 hours to make $10.

Ethan Brooks: And you won’t do that?

Evan: I just—fuck. It’s just knowing I could do that, or I could spend 15 minutes inside of a store, 10 minutes inside of a store, five minutes inside of a store sometimes, and then make enough money.

Brooks: There are a lot of ways you could describe Evan. But if we’re really getting down to it, a title that fits pretty well is “thief.” Over the last six years or so, Evan has dedicated many of his waking hours to stealing.

On a typical day, Evan—and I’m just going to use his first name to protect his privacy—Evan takes the train out of town from where he lives, in San Francisco, shoplifts all day, then comes back home. Sometimes he calls this his “job” or “going to work.” When he sleeps, it’s out on the street or in a shelter.

In Evan’s world, what he does is called being an “out-of-town booster,” as in someone who boosts, or steals, property from outside of San Francisco—

which, in his circle, affords him a certain amount of status: one rung higher on the ladder than an in-town booster.

Evan: The in-town booster isn’t making real money. You’re making, like, 20, 40 bucks a run.

Brooks: Okay.

Evan: But out-of-town boosters, somebody’s gonna be gone all day, going to a couple different stores and then coming back, making several hundred bucks.

Brooks: Evan steals so that he can sell. He’s had success converting Frappuccinos, Nutella, honey into cash. Tide Pods, apparently, are always in high demand. Lately, he’s been boosting Stanley cups from the Target in Emeryville, just north of Oakland.

[Music]

Brooks: He then takes the train to the Civic Center in San Francisco to sell to a middleman, who will sell the stolen Stanley cups to a diverter, who will repackage them and resell them on eBay. Evan is part of an economy that sells millions and millions of dollars of stolen goods every year.

Recently, this particular Target has been on Evan’s mind because he just cannot believe how easy it was to steal from them.

Evan: I literally went, like, 27 days in a row because I kept telling myself, If it doesn’t work, I’ll quit fentanyl. And it just kept working, and it kept working, and it kept working every day. And I was like, What is going—this is, like, a Groundhog’s Day or something.

Brooks: Another title you could give Evan, apart from thief, is “addict.” Fentanyl is the singular driving force behind his shoplifting.

In the eyes of the middlemen who resell what he steals, fentanyl makes Evan the ideal employee: highly motivated, with a huge tolerance for risk and nothing to lose.

In the real world, Evan is just a normal guy, a mechanic, and from what I’m told, a good one. But in San Francisco, as one of Evan’s oldest friends put it to me, he is the “King of the Fools.”

Evan: It didn’t really feel like that until I got to San Francisco.

Brooks: Uh-huh.

Evan: Everywhere else was super hard to make it, I feel like. Well, of course when I was there I didn’t really think that. Um, but When I got here, it was so much easier. Ow.

Brooks: You all right?

Evan: Yeah, my leg. Can you help me put this back just a little bit again? (Laughs.) I’m sorry.

Brooks: For sure. No problem, dude.

Brooks: Evan pauses our interview here and asks me to adjust his hospital bed.

Brooks: Like here, or all the way further down?

Evan: A little bit more. Right, that’s perfect.

Brooks: We’re sitting in Evan’s room in San Francisco General Hospital. Evan is propped up in bed wearing a paper gown, with an IV drip taped to his arm. There is a huge pile of candy next to his pillow: sour worms and Starburst and Twix that hospital staff gave him.

Addicts often get really intense sugar cravings. This happens for a lot of reasons, but in the end, a sugar high is still a kind of high.

At the moment we’re talking, Evan is in a bad way. He is visibly emaciated—with knobby elbows, rib cage on full display—and he’s struggling to control his body. Depending on what happens next, death, he thinks, is a real possibility.

I met Evan just a few months ago, about six weeks before this conversation in the hospital, and have followed along with him as he has made this journey from being an out-of-town booster, the “King of the Fools,” to where he is now.

Evan: We were watching this show last night about Vikings, and apparently, it was Viking tradition that when men or women would get older and they couldn’t hunt, fish, or farm or help get anything, that they would just go jump off a cliff and kill themselves ’cause they were a burden to their family.

Brooks: Mm-hmm.

Evan: And so I thought about that. But that’s the position I would be in if I was like, if that was back, you know, if it was the time we were in now. They’d be like, You can’t even help us do anything ’cause your leg is fucked up, and you can’t even eat a whole meal without vomiting, so we’re just gonna take you to the Valhalla cliffs or whatever and have you jump. Oh man.

[Music]

Brooks: Like Evan says, there are these places around Scandinavia where, supposedly, in early Norse society, the elderly and infirm leapt to their deaths when they had no more purpose to serve.

In the TV show Evan watched, there’s a shot of a man leaping off this huge, towering cliff and simply falling out of the frame. He disappears.

But the thing about this Viking tradition is that it’s just a story; it’s a myth. The cliffs are real enough, but there’s no evidence anyone ever jumped off them. The Vikings had to figure out a way to care for these people, just like the rest of us.

[Music]

Brooks: The weeks I spent following Evan, a period that ended with him in this hospital bed, were critical weeks for him. It was also a critical period for San Francisco, when the city began to change its approach to people like Evan, people who are in need of real care and whose presence threatens the health of the city.

From The Atlantic, this is No Easy Fix Episode 1, “The Vanishing Point.”

[Music]

Brooks: Back in the first years of the pandemic, a new type of video started showing up on YouTube and other corners of social media.

Tyler Oliveira: This is San Francisco—the city that pays drug addicts to use drugs?

Brooks: They had titles like “I Investigated the City of Real Life Zombies” and “I Investigated the City Where Every Drug Is Legal.”

Oliveira: Rampant homelessness, deadly drug addiction, and unpunished shoplifting and car break-ins. Businesses are fleeing, and the city is dying. But how did it get to—

Brooks: What they were showing, to audiences of millions and millions of people, were these places in American cities where it felt like the social order had broken down completely. City blocks and encampments crowdedwith people injecting, overdosing, and dying—all right out in the open.

Oliveira: —the center of America’s drug epidemic, overrun with a drug known as “tranq,” a mixture of horse tranquilizer and fentanyl that’s turning people there into real-life zombies.

Brooks: It wasn’t just San Francisco in the spotlight.There was Kensington Avenue in Philadelphia, Skid Row in Downtown L.A., encampments underneath I-5 in Seattle, the storm drains under the Las Vegas Strip.

There were, and still are, livestreams of these places broadcasting these images 24/7.

[Music]

Brooks: The videos gave these places a new notoriety. And it was San Francisco—specifically, the Tenderloin neighborhood—that was maybe the most infamous.

There was the reality of the thing, and I’ll just give one stat here to illustrate this: In this period, nearly twice as many people died of overdose in San Francisco than died of COVID-19. Fentanyl killed far more people than the pandemic.

Then there was this contrast that wasn’t quite the same as anywhere else: needles and human waste covering the sidewalk, signs of the most self-destructive, destitute humanity, in the same city at the cutting edge of this new technology that can write and speak like a human.

**Joe Wynne:**From the outside, it’s, like, this really grotesque cesspool, but once you’re in there, it’s a bizarrely normal social situation.

Joe Wynne has spent a fair amount of time among people dealing with addiction in the Tenderloin, not because he’s lived there himself, but because he is Evan’s best friend—from before Evan got wrapped up in fentanyl.

Brooks: Do you remember the first time you met Evan?

Wynne: Yeah, he was a mechanic at this high-end, custom 4x4r shop in North Carolina.

Brooks: Before living on the streets in San Francisco, Evan worked as a mechanic in North Carolina. The shop he worked for is a sort of Pimp My Ride for wealthy, crunchy digital nomads looking to live the van life for a while.

Joe is not a digital nomad, but he’s wealthy enough and at least a little crunchy. So back then, he enlisted Evan and the shop where he worked to outfit his camper van.

At the time—this was around 2013—Joe was traveling and living out of his van and, with it in the shop, didn’t have a place to live.

Wynne: And Evan was like, You can sleep in my basement. And after, like, half a day there, they’re like, Oh, you can move into the guest bedroom; it’s totally available. You’re not a crazy person.

Brooks: So Joe and Evan became friends not so long ago because Evan offered Joe a place to stay. And they had a lot in common: They both love cars, they both became fathers when they were quite young, and they’re both relentlessly outgoing.

Wynne: He’s one of the most charming people I’ve ever met. If you leave him alone in a group of four or five strangers, he will be best friends with everybody inside of 30 minutes. He’s absolutely a life-of-the-party kind of guy and not in the big, loud, over-the-top way, in the kind of goes around and has a really great conversation with everyone where they feel like the center of the room. That’s really his superpower, is, I feel like, is that type of little conversational loop with people.

Brooks: When Joe’s van was finished, they went their separate ways. Eventually, Joe went on to start a cannabis company in Northern California; Evan stayed in North Carolina.

But they stayed in touch, got to know each other more, and Joe started noticing another side of Evan too.

Wynne: There’s, like, two sides: There’s Evan and Melvin. Melvin is malicious Evan, or, like, the evil side inside of him that completely takes over, but I almost never see it. I see the aftermath of it, but he never lets me see full-blown.

Brooks: If there were drugs around, Evan would do as much as he could. To Joe, it felt like he didn’t understand how a sacrifice in the present might be beneficial in the future.

[Music]

Despite the lurking threat of Melvin, around 2016, Joe convinced Evan to move out to California to work for him at his cannabis company. They manufactured the oils in THC pens. Evan managed a team; Joe considered him his right-hand man.

Joe had a strict “no hard drugs” policy for his employees, and one day, Evan slipped.

Wynne: So I had a drug-test kit on-site, so I told him, I said, Hey, we’re going out back, and let’s go piss in a cup. And he was like, Oh, oh, oh—you know, he started to freak out. And I tested him, and it was the thickest blue line for positive opiates ever, so I took him back to his room, and we loaded up everything he owned, and I said, I just can’t carry you if you’re gonna do that.

It was excruciating, man; it was bad, and I knew it was gonna go worse. But I just couldn’t have it go worse in my living room. I had a lot of people who were counting on us to make good decisions to feed their families. And it was one of the toughest days ever in my business career ’cause he was absolutely my best friend, and I felt like, that day, I felt like it was like signing his death warrant.

Brooks: Once he separated from Joe, it didn’t take Evan too long to make his way down to San Francisco. When Evan discovered that he could shoplift and sell what he stole and buy fentanyl all in the same place, he never left. That economy, the ease with which he could support his habit, is what kept him there.

Joe went on to sell his company for a lot of money. He told me that after the sale, many of his employees got bonuses big enough for a down payment on a house. Evan, meanwhile, stole Tide Pods and slept on the street.

Wynne: I would fight anything to change it. If there was any series of tasks I could go through to get my best friend back—even if I didn’t get him back, even if he just got his life back—I would go through hell, ’cause like Evan, I love a challenging, knives-and-daggers, bleeding-in-the-streets fight for something that’s worth it. And for my best friend who helped me—I’m living my dream life right now: I live in my dream home with the greatest partner I could ever have. My kid goes to a wonderful school and is blossoming. The car that me and Evan always talked about—the insanity car, the insane race car—it’s in the garage, right?

Brooks: (Laughs.)

Wynne: And I’ve completed all life dreams, and I’m having to literally spend time making up new ones.

I would do anything to help him get back his portion of the dream ’cause he helped me get mine.

Brooks: Over the years, Joe has tried to give Evan back his portion of that dream.

One time, he tracked Evan down in the Tenderloin, rented a penthouse suite for them both, with a Jacuzzi tub. I’ve seen the pictures of Evan looking like a wet dog in a tub he has single-handedly turned absolutely filthy.

Joe tried, simply, to return that favor that Evan offered him when they met: a place to live.

Wynne: I was just like, Hey, and I talked to him about it, and I said, Hey, I’m living alone on this land up north. The wife has not moved in. I was like, You could move in and go through horrific withdrawal and be a total piece of shit, and nobody would know except me. You can hang out. I’ll put you on salary. You’ll make a little money—

Brooks: Yeah.

Wynne: And he was like, he just literally said it: He’s like, Yeah, I’m not done yet. (Laughs.) I’m not finished—

Brooks: Not done yet?

Wynne: Yeah. I’m not—I don’t think I’m done yet.

[Music]

Brooks: Evan is just one of over 4,000 unsheltered people living in San Francisco. “Unsheltered,” by this count, means living on the street, bus stations, parks, tents, and abandoned buildings. There are around 4,000 more in temporary shelters.

Nationally, those numbers are even more grim.

In 2024, the number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night was 771,480, the highest number ever recorded in the United States.

To be very clear, “I’m not done yet” is by no means a representative attitude of that whole. Unsheltered life is grueling—sometimes violent, and often deadly. Evan’s willingness to leave that behind, or not, doesn’t change that fact.

There are many reasons why so many people in America are homeless, first among them being a lack of homes. It’s no coincidence that things are so rough in one of the most expensive cities in America, while in places like West Virginia, which has its own opioid crisis and much cheaper housing, unsheltered homelessness is much more rare.

[Applause]

Brooks: This year, San Francisco elected a new mayor, Daniel Lurie, an ultra-wealthy moderate in a city famous for its progressive politics.

Daniel Lurie: Today marks the beginning of a new era of accountability and change at city hall, one that, above all else, serves you, the people of San Francisco.

Brooks: The new mayor has his work cut out for him. San Francisco has become emblematic of what sometimes gets called a “doom loop,” something that has happened in a lot of cities since the pandemic.

In this loop, the office buildings empty out because of the pandemic and remote work. The stores and restaurants that served office workers are forced to shutter. Crime soars. Tax revenues fall. Public transportation is forced to cut back, so even fewer people come downtown. And on and on and on.

Lurie is not a tough-on-crime mayor. He’s not gutting the city’s addiction and homelessness services.

But the way he spoke about these problems, which was the first topic in his inauguration speech, was different.

Lurie: I entered this mayor’s race not as a politician, but as a dad who couldn’t explain to my kids what they were seeing on our streets.

Brooks: Lurie talks about what he could see—what the problem looks like, the effect of this constant onslaught of imagery on individual well-being.

Lurie: Widespread drug dealing, public drug use, and constantly seeing people in crisis has robbed us of our sense of decency and security.

Now, safety isn’t just a statistic; it’s a feeling you hold when you’re walking down the street. That insecurity is—

Brooks: One reason he might be using these terms is that, by the numbers, the unsheltered, visible homeless population in San Francisco is nearly the same as it was 10 years ago. What has changed is everyone else.

It’s hard to get exact numbers, but downtown San Francisco has lost about two-thirds of its daytime population—that’s hundreds of thousands of commuters and office workers gone, which leaves just Evan and people like him.

This, in short, might be called a visibility problem.

People feel scared and maybe a little ashamed having to see so many people experiencing homelessness every day,which is an odd problem because for many people living on the street, a family member, or a loved one, is looking for them.

[Music]

Brooks: Visible to a city that sees too much of them. invisible to families who would love nothing more than to see them.

That’s after the break.

[Break]

Brooks: In late February, about six weeks before Evan would find himself in the hospital, I met Liz Breuilly. Liz is in her 40s and lives in the mountains outside of San Francisco.

She lives a sort of double life. Her day job is in the medical field, and in her spare time, she does something else.

Liz Breuilly: I’m not a private investigator. Nobody’s paying me and nobody’s licensing me to do the work that I do.

Brooks: How would you describe what you do?

Breuilly: (Laughs.)I feel like I started doing one thing, right, in the beginning, several years ago, and I feel like it’s evolved into many different things.

Brooks: Mm-hmm.

Breuilly: Primarily, I would say that I locate missing persons that are either mentally ill, drug-addicted, and/or experiencing homelessness.

Brooks: Liz finds missing people. She does this for free. I’ve asked her probably 25 times why she does this, and even to her, it’s not clear.

[Music]

What is clear is that there’s plenty of finding to do.

There are around 1,400 people on the San Francisco Police Department’s missing-persons list. And given that “missing” just means that someone somewhere is looking for you—and has filed a police report—that number could be much higher.

[Music]

Brooks: Liz and others who spend time in the Tenderloin and encampments think that many of these people are here—which is strange, considering all of these disappeared people are far more visible than those of us spending our days in cars and offices, our nights in houses and apartments and bedrooms, while they’re out on the street, exposed.

In these first couple months of the new mayoral administration, the city has been experimenting with new solutions to this problem of unsheltered homelessness and open drug use.

There have been mass arrests of dealers and users, pushing the jail population to levels that haven’t been seen in years.

One corner of the Tenderloin was turned into a triage center, which has since shut down, where people could go for coffee, to be connected with city services, and be offered a free bus ticket out of town, courtesy of the city.

But there’s no city program that does what Liz does. She’s a sort of one-woman case study of a different approach, a radical approach, to this problem: reconnect lost people with their families and see if things change.

Breuilly: Most of the time, when families get to me, they think their loved one is deceased. And so they’re almost just looking for validation that that’s the case, and it’s usually not. I have located, I don’t know, well over 200 people, maybe 2—I don’t even know. It’s been well over 200.

Brooks: Evan was once one of Liz’s lost people.

Brooks: Do you remember who reached out to you about him the first time?

Breuilly: Mm-hmm, yeah, his sister did. His sister did. He had been missing for several years, and she basically was, you know, said, This is my brother, and I heard what you do, and I’m wondering if you would help me. And I said, Sure.

Brooks: There’s no big secret to how Liz works. She asks families about their missing person, about their history of addiction and mental illness. She checks arrest records. She’s in frequent contact with the city morgue. But mostly, she just adds pictures, like Evan’s picture, to a folder in her phone, memorizes faces as best she can, and starts looking.

And then, one day, there Evan was.

Breuilly: So I roll down the window, and I scream, “Evan! Evan!” (Laughs.) And he stopped, and he looked at me, and he ... (Laughs.) He basically was like, I don’t know you.

And I’m shouting at him from my car, and I said, No, you don’t know me. I just need to talk to you for a second.

And that’s what started a, I don’t know, four-year friendship, right, with him.

Brooks: Did Evan call his sister when you—

Breuilly: No.

Brooks: —caught up with him? No?

Breuilly: No, he did not. He just couldn’t do it.

Brooks: A lot of people who Liz finds don’t call their families. Many of them do call but don’t leave the street or go home. One person I met through Liz put it this way: “I don’t want to be missing, and I don’t want to be found either.”

So this limbo—not missing, not found—is where many of Liz’s people stay for years.

Breuilly: Every time they hear about someone overdosing or every time someone posts a video of a sheet over somebody, I’m getting a phone call from five parents asking me if I know who it is and if that’s their kid.

Brooks: Liz and I are driving around downtown San Francisco. A lot of open drug use and encampments that were concentrated in the Tenderloin are now more diffuse.

In the Mission District, the alley behind the Everlane is packed with people smoking, injecting, laid out. Once in a while, a cleanup crew drives through, clears everyone out, hoses the alley down, and then everyone comes back.

Breuilly: People were never spread out like this. I mean, there would be, in certain areas, I mean, at nighttime, there’d be 250, 300 people. And at nighttime, it still gets like that when the cops run around, but because the cops are really doing a lot of work with patrolling and doing all this stuff, it breaks them up.

Brooks: Today, Liz has been looking for one guy in particular. A few weeks ago, he had asked her to find his mom, and Liz learned pretty quickly that his mom had passed away.

Breuilly: So—but I also know that if I don’t tell him, no one else will.

Brooks: Yeah, ’cause nobody even knows, right?

Breuilly: Yeah, and the only way to reach him is to do what we’re doing today, which is going back out on the street to find him.

Brooks: Late in the afternoon, she sees the guy she’s looking for.

Breuilly: I think that’s him. I think that’s the guy.

Brooks: The man is wearing a red flannel and a corduroy jacket, with a set of neon ski goggles around his neck. He’s half-standing out of his wheelchair, leaning over a row of trash cans, digging through the garbage and throwing things aside.

Here’s what will happen next: Liz will tell him the news—that his mother has passed away. He will cry and thank Liz for telling him. They’ll smoke cigarettes together, even though Liz doesn’t smoke cigarettes, for 10 minutes and then 20 minutes as he tries to adjust to this new reality.

But before any of this can happen, there’s a problem: The street we’ve pulled over in is narrow and behind us, suddenly, is a white Jaguar SUV with no one in the driver’s seat. A self-driving car is stuck behind us, with traffic backing up behind it, preventing this volunteer bearer of the worst possible news from doing her job.

Breuilly: Well, it’s definitely a feeling of helplessness, right? This kid is very, very sick. Yes, am I glad I was able to give him the information and hopefully set him free a little bit from this persistent state of looking? But in the same respect, it’s like I’m leaving somebody a little bit worse than in the situation they were in.

And so it’s deflating because, even me, who is really—I know the resources in the city. But right now, there’s nowhere to take him.There’s no space in shelters. He doesn’t have a phone. I can’t bring him home to my house. What am I gonna do?

[Music]

Brooks: It’s not just San Francisco trying to ram a metaphorical self-driving car through a metaphorical alley of grief. Cities around the country are desperate to move on.

Portland, Oregon, elected a new mayor who pledged to end unsheltered homelessness, after the state re-criminalized drug possession, after decriminalizing in 2021.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, elected a tough-on-crime mayor, and hired more police.

Fremont, California, criminalized not just homeless encampments but “aiding” and “abetting” homeless encampments in any way.

Everyone, from city leadership to regular people like Liz, seem desperate to move on and willing to try new things. Liz, in part, does this work because no one else will.

Brooks: It’s night now, and Liz is still out looking for a few missing people. And, tucked up behind the passenger-side visor in her car, Liz has a bundle of printed-out emails from Evan’s family and a picture of his kid, a middle schooler now, playing the clarinet.

At night, the plaza at 16th and Mission turns into a packed open-air market of stolen goods. The sellers, mostly are addicts, are hawking used clothes, kids’ toys, tamales, phone chargers, a tricycle, and remarkably, tonight, an enormous slab of bacon. The shoppers are mostly low-income San Franciscans chasing a good deal. Behind them are the dealers, many of them young Honduran men in masks.

Hundreds of people are walking around this dark patch of concrete. Cash moves in one direction: from the buyers to the sellers to the dealers.

Standing on one corner, leaning against a street sign, is Evan.

Evan: Every time, every time—like, the last, what, like, five times, it seems like—I’ve been like, I really need to see Liz today. I need to see Liz. Today, I literally kept thinking today—

(Dog barks.)

Evan: —I was like, I need to find her. I need to find her.

Breuilly: Here I am.

Brooks: This is the first time I met Evan, weeks before our conversation in the hospital.

Evan is looking shaggy, but in relatively good health. And he swears that when he needs Liz, he can manifest her.

Breuilly: How are you, though? Why did you manifest me?

Evan: Because I’m, I have to figure something out.

Breuilly: Okay, what’ve you got going?

Brooks: Evan tells Liz that he hasn’t been able to keep much food down for weeks. And his legs are infected and extremely swollen.

Leg infections are common for fentanyl users like Evan due to contaminants in the supply and side effects from injection. It’s why you see so many people in wheelchairs.

Breuilly: How is it? Ooh, it … (Gasps.)

Evan: Yeah—

Breuilly: Evan!

Evan: I know, that’s what I’m saying. So I need, I need some, I need, I’m—I, with my leg and my stomach, I was like, I’m over this.

Breuilly: Oh, wow.

Evan: I’m so over it. I’m so over it. And I’m, like, I’m just ready—

Breuilly: Pitiful.

Evan: —for something to change, something—

Breuilly: Yay!

Evan: (Laughs.)

Brooks: Liz, as Evan is speaking, is beaming. This was a full 180 from the “I’m not done yet” Evan told Joe when he tried to get him off the street a few years ago.

This was the first time in the years Evan and Liz have known each other that Evan has said he wanted to get off the street and get off fentanyl.

Evan: Yeah, I’m falling apart, and I’m, in a way, I’m kind of glad. (Laughs.) ’Cause I’m—it’s kind of making me turn to stop.

Brooks: Yeah.

[Music]

Brooks: It might not sound like much, but when someone like Evan, who has been addicted to opioids for many, many years, says, “I’m ready,” this is the moment that San Francisco’s, and many cities’, strategy to address this problem is built on.

So here we were: Evan is ready to get off the street; the city of San Francisco is eager to help.

Evan’s readiness is supposed to trigger action—a chance to put a dent in this visible suffering that haunts the mayor and so many other San Franciscans. Plus, Evan’s got Liz, who has a car and a phone. How hard could it be?

That’s next week.

[Music]

No Easy Fix is produced and reported by me, Ethan Brooks. Editing by Jocelyn Frank and Hanna Rosin. Engineering by Rob Smierciak. Fact-checking by Sam Fentress. Claudine Ebeid is the executive producer of Atlantic audio. Andrea Valdez is our managing editor.

See you next week.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

Ng Han Guan / APTimo Barthel of Germany competes in the men’s 3m springboard-diving preliminaries at the World Aquatics Championships in Singapore on July 31, 2025.

Ng Han Guan / APTimo Barthel of Germany competes in the men’s 3m springboard-diving preliminaries at the World Aquatics Championships in Singapore on July 31, 2025. Vincent Thian / APGreece's Dimitrios Skoumpakis attempts a shot at goal during the men’s water-polo semifinal at the World Aquatics Championships in Singapore on July 22, 2025.

Vincent Thian / APGreece's Dimitrios Skoumpakis attempts a shot at goal during the men’s water-polo semifinal at the World Aquatics Championships in Singapore on July 22, 2025. Edgar Su / ReutersOpen-water swimmers dive into the water at the start of the mixed 4x1500m race at Sentosa Island, Singapore, on July 20, 2025.

Edgar Su / ReutersOpen-water swimmers dive into the water at the start of the mixed 4x1500m race at Sentosa Island, Singapore, on July 20, 2025. Marko Djurica / ReutersSwitzerland’s Jean-David Duval dives during the men’s 27m high-dive semifinals on Sentosa Island on July 25, 2025.

Marko Djurica / ReutersSwitzerland’s Jean-David Duval dives during the men’s 27m high-dive semifinals on Sentosa Island on July 25, 2025. Hollie Adams / ReutersCanada’s Kylie Masse swims in the women’s 50m backstroke semifinals on July 30, 2025.

Hollie Adams / ReutersCanada’s Kylie Masse swims in the women’s 50m backstroke semifinals on July 30, 2025. Maddie Meyer / GettyHannes Daube of Team United States and Lorenzo Bruni of Team Italy wrestle in the Classification 7th–8th Place match for men’s water polo on day 14 of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships.

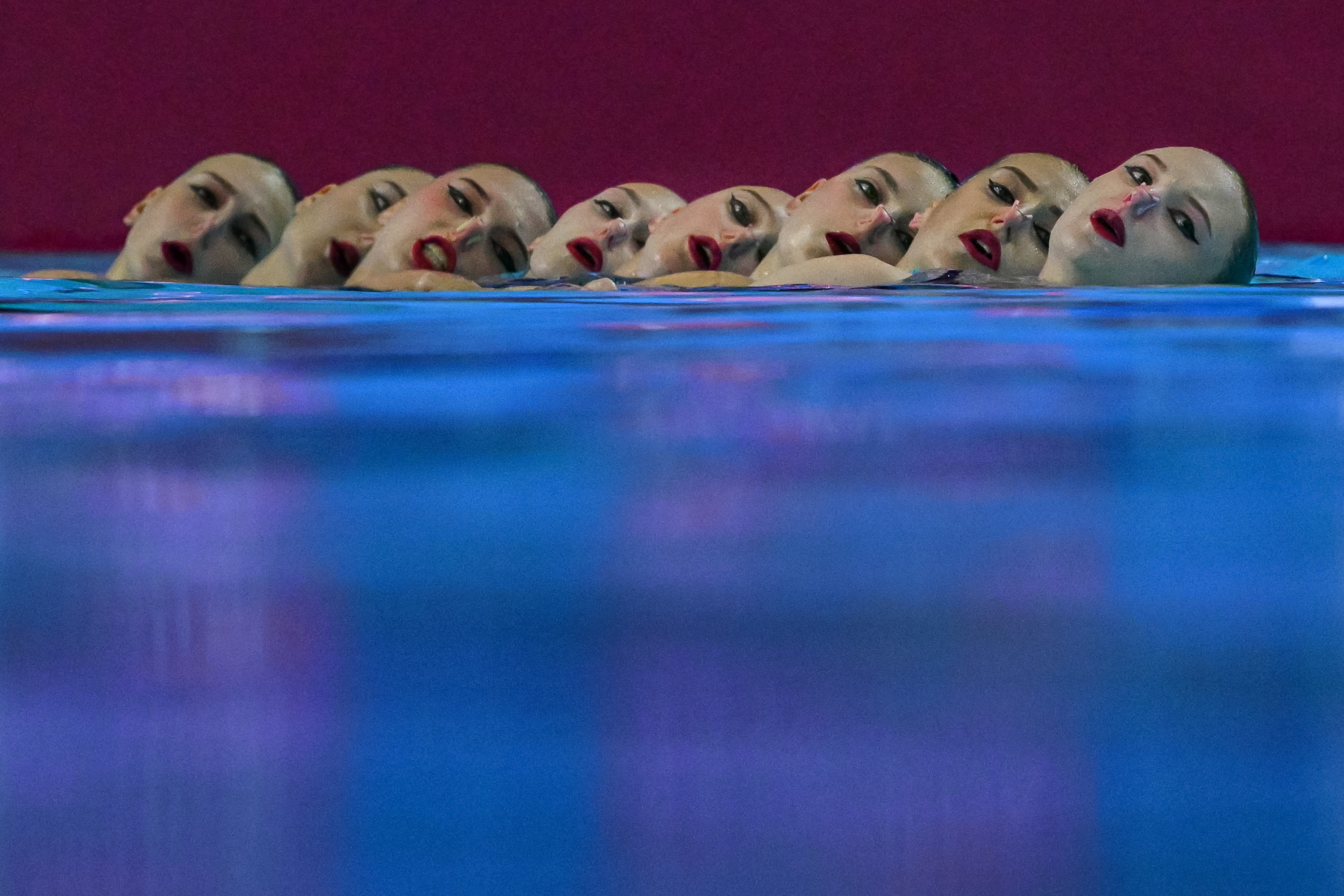

Maddie Meyer / GettyHannes Daube of Team United States and Lorenzo Bruni of Team Italy wrestle in the Classification 7th–8th Place match for men’s water polo on day 14 of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships. Adam Pretty / GettyTeam China competes in the Team Technical Preliminaries on day 11 of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships on July 21, 2025.

Adam Pretty / GettyTeam China competes in the Team Technical Preliminaries on day 11 of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships on July 21, 2025. Lee Jin-man / APZoi Karangelou of Greece competes in the Women’s Solo Free preliminary of artistic swimming on July 20, 2025.

Lee Jin-man / APZoi Karangelou of Greece competes in the Women’s Solo Free preliminary of artistic swimming on July 20, 2025. Adam Pretty / GettyGold medalists Mayya Gurbanberdieva and Aleksandr Maltsev of Team Neutral Athletes B pose on the podium during the Mixed Duet Technical Final medal ceremony on July 23, 2025.

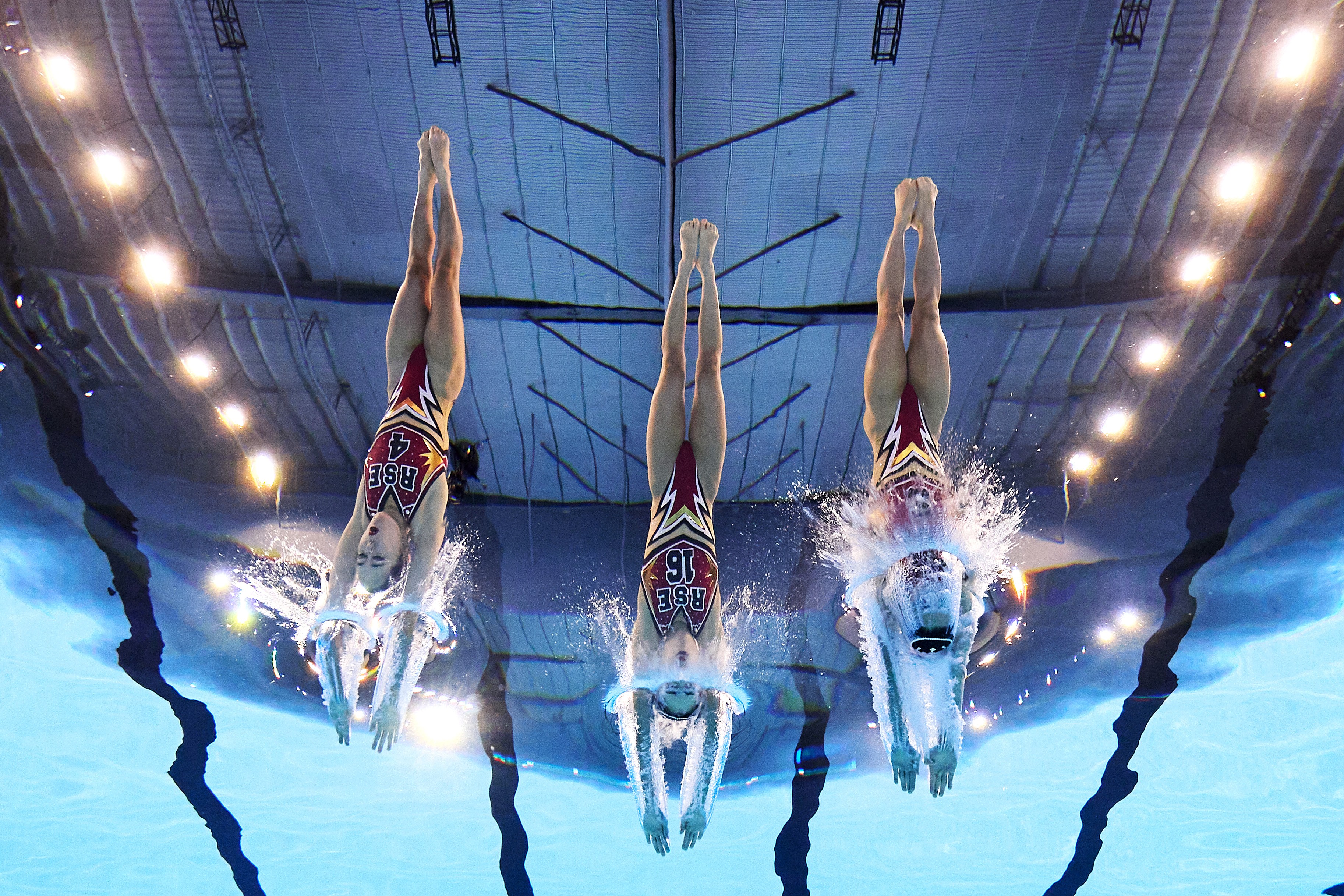

Adam Pretty / GettyGold medalists Mayya Gurbanberdieva and Aleksandr Maltsev of Team Neutral Athletes B pose on the podium during the Mixed Duet Technical Final medal ceremony on July 23, 2025. Adam Pretty / GettyShu Ohkubo and Rikuto Tamai of Team Japan compete in the men’s 10m synchronized-diving final on Day 19.

Adam Pretty / GettyShu Ohkubo and Rikuto Tamai of Team Japan compete in the men’s 10m synchronized-diving final on Day 19. Adam Pretty / GettyTeam Croatia gets into position prior to a preliminary-round match against Team Montenegro in men’s water polo at the OCBC Aquatic Center on July 14, 2025.

Adam Pretty / GettyTeam Croatia gets into position prior to a preliminary-round match against Team Montenegro in men’s water polo at the OCBC Aquatic Center on July 14, 2025. Francois-Xavier Marit / AFP / GettyTeam Neutral Athletes competes in the final of the Team Free artistic-swimming event on July 20, 2025.

Francois-Xavier Marit / AFP / GettyTeam Neutral Athletes competes in the final of the Team Free artistic-swimming event on July 20, 2025. Yong Teck Lim / GettyNicholas Sloman of Team Australia warms up ahead of the men’s 3km knockout sprint heat on day nine of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships.

Yong Teck Lim / GettyNicholas Sloman of Team Australia warms up ahead of the men’s 3km knockout sprint heat on day nine of the 2025 World Aquatics Championships. Oli Scarff / AFP / GettyThe Canadian swimmer Summer McIntosh reacts after competing in a semifinal of the women's 200m butterfly on July 30, 2025.

Oli Scarff / AFP / GettyThe Canadian swimmer Summer McIntosh reacts after competing in a semifinal of the women's 200m butterfly on July 30, 2025. Adam Pretty / GettyTeam Japan competes in the Team Technical Final on day 12, at the World Aquatics Championships Arena in Singapore.

Adam Pretty / GettyTeam Japan competes in the Team Technical Final on day 12, at the World Aquatics Championships Arena in Singapore. Yong Teck Lim / GettyTeam Spain competes in the Team Free Final on day 10.

Yong Teck Lim / GettyTeam Spain competes in the Team Free Final on day 10. Vincent Thian / APKatie Ledecky of the United States celebrates after winning the gold medal in the women’s 1500m freestyle final on July 29, 2025.

Vincent Thian / APKatie Ledecky of the United States celebrates after winning the gold medal in the women’s 1500m freestyle final on July 29, 2025. Ng Han Guan / APGabriela Agundez Garcia and Alejandra Estudillo Torres of Mexico compete in the women’s 10m synchronized-diving preliminaries on July 28, 2025.

Ng Han Guan / APGabriela Agundez Garcia and Alejandra Estudillo Torres of Mexico compete in the women’s 10m synchronized-diving preliminaries on July 28, 2025. Sarah Stier / GettyOsmar Olvera Ibarra of Team Mexico reacts after a dive during the men’s 3m springboard preliminaries on day 21.

Sarah Stier / GettyOsmar Olvera Ibarra of Team Mexico reacts after a dive during the men’s 3m springboard preliminaries on day 21. Manan Vatsyayana / AFP / GettyThe Team USA swimmer Kate Douglass competes in the final of the women’s 100m breaststroke on July 29, 2025.

Manan Vatsyayana / AFP / GettyThe Team USA swimmer Kate Douglass competes in the final of the women’s 100m breaststroke on July 29, 2025. Sarah Stier / GettyMelvin Imoudu of Team Germany competes in the men’s 50m breaststroke heats on day 19.

Sarah Stier / GettyMelvin Imoudu of Team Germany competes in the men’s 50m breaststroke heats on day 19. Francois-Xavier Marit / AFP / GettyThe Team China divers Cheng Zilong and Zhu Zifeng compete in the final of the men’s 10m platform synchronized-diving event on July 29, 2025.

Francois-Xavier Marit / AFP / GettyThe Team China divers Cheng Zilong and Zhu Zifeng compete in the final of the men’s 10m platform synchronized-diving event on July 29, 2025. Maye-E Wong / ReutersTeam Spain performs during the Team Acrobatic Artistic Swimming Final at the Singapore 2025 World Aquatics Championships on July 25, 2025.

Maye-E Wong / ReutersTeam Spain performs during the Team Acrobatic Artistic Swimming Final at the Singapore 2025 World Aquatics Championships on July 25, 2025. Illustration by Ben Denzer

Illustration by Ben Denzer Ross Harried / NurPhoto / Getty

Ross Harried / NurPhoto / Getty

Illustration by Matteo Giuseppe Pani / The Atlantic

Illustration by Matteo Giuseppe Pani / The Atlantic Illustration by Diana Ejaita

Illustration by Diana Ejaita Mohammed Y. M. Al-yaqoubi / Anadolu / GettyFive-year-old Lana Salih Juha, who fled with her family from Gaza's Shuja'iyya neighborhood to the city center, suffers from severe malnutrition, seen on July 28, 2025. Her family is calling for urgent help to ensure she receives proper treatment and nutrition.

Mohammed Y. M. Al-yaqoubi / Anadolu / GettyFive-year-old Lana Salih Juha, who fled with her family from Gaza's Shuja'iyya neighborhood to the city center, suffers from severe malnutrition, seen on July 28, 2025. Her family is calling for urgent help to ensure she receives proper treatment and nutrition. Majdi Fathi / NurPhoto / GettyPalestinians gather at a food-distribution point in Gaza City on July 20, 2025.

Majdi Fathi / NurPhoto / GettyPalestinians gather at a food-distribution point in Gaza City on July 20, 2025. Mohammed Arafat / APTrucks carrying humanitarian aid line up to enter the Rafah crossing between Egypt and the Gaza Strip on July 27, 2025.

Mohammed Arafat / APTrucks carrying humanitarian aid line up to enter the Rafah crossing between Egypt and the Gaza Strip on July 27, 2025. Saeed M. M. T. Jaras / Anadolu / GettyPalestinians climb aboard a food-aid truck after walking for miles to receive flour distributed from several trucks that entered the area of Zikim, a kibbutz in southern Israel, on July 27, 2025.

Saeed M. M. T. Jaras / Anadolu / GettyPalestinians climb aboard a food-aid truck after walking for miles to receive flour distributed from several trucks that entered the area of Zikim, a kibbutz in southern Israel, on July 27, 2025. Ramez Habboub / GocherImagery / Future Publishing / GettyPalestinians carry humanitarian aid distributed at the Zikim crossing, near the Al-Sudaniya area in northern Gaza, as they return to their families after the beginning of airdrop operations.

Ramez Habboub / GocherImagery / Future Publishing / GettyPalestinians carry humanitarian aid distributed at the Zikim crossing, near the Al-Sudaniya area in northern Gaza, as they return to their families after the beginning of airdrop operations. Ramez Habboub / ABACA / ReutersA boy carries a bag of flour that was distributed at the Zikim crossing on July 26, 2025.

Ramez Habboub / ABACA / ReutersA boy carries a bag of flour that was distributed at the Zikim crossing on July 26, 2025. Mahmoud Issa / Anadolu / GettyPalestinians carry large sacks of flour away from a distribution point in the Zikim area on July 27, 2025.

Mahmoud Issa / Anadolu / GettyPalestinians carry large sacks of flour away from a distribution point in the Zikim area on July 27, 2025. Hassan Jedi / Anadolu / GettyResidents of the Nuseirat refugee camp line up in front of water trucks every day to collect clean water to carry back to their tents in Gaza City, seen on July 20, 2025.

Hassan Jedi / Anadolu / GettyResidents of the Nuseirat refugee camp line up in front of water trucks every day to collect clean water to carry back to their tents in Gaza City, seen on July 20, 2025. Abdalhkem Abu Riash / Anadolu / GettySacks of lentils are poured into cooking pots at a food-distribution station run by a charity organization in the Gaza Strip, seen on July 18, 2025.

Abdalhkem Abu Riash / Anadolu / GettySacks of lentils are poured into cooking pots at a food-distribution station run by a charity organization in the Gaza Strip, seen on July 18, 2025. Abdel Kareem Hana / APPalestinians struggle to get donated food at a community kitchen, in Gaza City, on July 26, 2025.

Abdel Kareem Hana / APPalestinians struggle to get donated food at a community kitchen, in Gaza City, on July 26, 2025. Khames Alrefi / Anadolu / GettyA child is seen among a crowd waiting to get hot meals distributed by an aid organization in Gaza City on July 26, 2025.

Khames Alrefi / Anadolu / GettyA child is seen among a crowd waiting to get hot meals distributed by an aid organization in Gaza City on July 26, 2025. Omar Al-Qattaa / AFP / GettyA displaced Palestinian girl takes a sip of lentil soup that she received at a food-distribution point in Gaza City on July 25, 2025.

Omar Al-Qattaa / AFP / GettyA displaced Palestinian girl takes a sip of lentil soup that she received at a food-distribution point in Gaza City on July 25, 2025. Jehad Alshrafi / APHumanitarian aid is air-dropped over Gaza City to Palestinians on July 27, 2025.

Jehad Alshrafi / APHumanitarian aid is air-dropped over Gaza City to Palestinians on July 27, 2025. Abdel Kareem Hana / APAid packages drop to the ground in the northern Gaza Strip on July 27, 2025.

Abdel Kareem Hana / APAid packages drop to the ground in the northern Gaza Strip on July 27, 2025. Abdel Kareem Hana / APA Palestinian youth carries a sack of aid that landed in the Mediterranean Sea, off the shore of Zawaida, after being air-dropped over central Gaza on July 29, 2025.

Abdel Kareem Hana / APA Palestinian youth carries a sack of aid that landed in the Mediterranean Sea, off the shore of Zawaida, after being air-dropped over central Gaza on July 29, 2025. Jehad Alshrafi / APPalestinians carry sacks of flour unloaded from a humanitarian aid convoy that reached Gaza City from the northern Gaza Strip on July 22, 2025.

Jehad Alshrafi / APPalestinians carry sacks of flour unloaded from a humanitarian aid convoy that reached Gaza City from the northern Gaza Strip on July 22, 2025. Jehad Alshrafi / APYazan Abu Ful, a malnourished 2-year-old child, sits at his family home in the Shati refugee camp in Gaza City on July 23, 2025.

Jehad Alshrafi / APYazan Abu Ful, a malnourished 2-year-old child, sits at his family home in the Shati refugee camp in Gaza City on July 23, 2025. Steph Chambers / Getty

Steph Chambers / Getty Illustration by Matteo Giuseppe Pani / The Atlantic. Sources: Will Heath / NBC / NBCU Photo Bank / Getty.

Illustration by Matteo Giuseppe Pani / The Atlantic. Sources: Will Heath / NBC / NBCU Photo Bank / Getty.