Subscribe here: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Overcast | Pocket Casts

President Donald Trump’s two most recent international summits—in Alaska last week with Russian President Vladimir Putin, and then at the White House this week with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky—included some notable fashion statements. Zelensky arrived in a proper suit instead of the military-style fatigues that he wore the last time he met with Trump, in February. But the more startling sartorial choice came from Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov: Lavrov arrived in Alaska in a sweatshirt (already a bold choice), and this one was adorned in big, black block letters with C.C.C.P., the Russian initials for the U.S.S.R. The message was widely interpreted as a rallying cry for old-style Russian imperialism and a somewhat trollish move by the foreign minister, who had arrived at a meeting ostensibly designed to discuss ending that very thing. But maybe the more urgent question is: Was the significance of this message entirely lost on Trump?

On the campaign trail ahead of his second term, Trump repeatedly said that he would end the Ukraine war within 24 hours of taking office. With this latest pair of summits, Trump was equally optimistic: Close the deal! Win the Nobel Prize! But the forces driving this war—Putin’s nostalgia for a bygone era among them—are too deep and stubborn to easily yield to Trump’s brand of dealmaking.

In this episode of Radio Atlantic, we talk with Anne Applebaum, who has been studying Ukraine and Russia for decades and understands their leaders’ underlying motivations. We also speak with politics and national-security writer Vivian Salama, who knows what Trump’s limitations are and explains what the next possible moves could be.

The following is a transcript of the episode:

Hanna Rosin: The past seven days brought two very strange international summits: one where President Donald Trump rolled out an actual red carpet on American soil for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

News host 1: A high-stakes moment on the world’s stage.

News host 2: It was Putin’s first time back on U.S. soil in more than a decade. He received a grand welcome, complete with a military flyover and a red-carpet rollout.

Rosin: A few days later, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky visited the White House with a hastily mobilized posse of European leaders.

News host 3: The historic sequel: President Trump and Ukraine’s President Zelensky back at the White House.

News host 4: The two leaders striking a cordial, collegial tone and also somewhat optimistic.

Rosin: The summits were historic, momentous—if more than a little chaotic. And yet it’s unclear what, if anything, changed as a result of them. The war grinds on. Civilians are still dying in Ukrainian cities, with Russians striking even as Zelensky was in Washington.

Trump approached the two Ukraine talks with his usual brand of optimism. Let’s close the deal! Win the Nobel Prize! But—and this will come as a huge shock—ending a war is not so simple.

I’m Hanna Rosin. This is Radio Atlantic.

To help us understand what happened this week, what changed and what didn’t, and what really needs to happen for this to end well, we have staff writer Anne Applebaum, a longtime reporter on both Russia and Ukraine, and staff writer Vivian Salama, who covers politics and national security.

Vivian, welcome to the show.

Vivian Salama: Thanks for having me.

Rosin: Anne, thanks for joining us.

Anne Applebaum: Thanks, Hanna.

Rosin: And before we begin, I want to say that we’re recording this conversation at 10 a.m. Eastern Time on Wednesday because anything could happen. This is an evolving story.

Vivian, you were actually at the White House for Monday’s meeting between Trump, Zelensky, and the European leaders. What did you take from watching it up close that the rest of us might not have seen?

Salama: I have covered the White House now since, let’s say, late 2016, when Donald Trump was elected the first time. And I have to say, I’ve never, ever seen the White House so chaotic.

Rosin: Really?

Salama: I’ve never seen so many people, journalists included, and I’m not talking about just European and American journalists. There were Iranian journalists and Japanese journalists—I mean, just to show you how significant an event this was and how much the world is sort of looking at Washington at that moment to see if this would indeed result in a breakthrough, or if it’s just talks to have more talks.

Rosin: So what you took from that is: The world’s eyes are watching. Like, that was the symbolism for you, or was it that chaos is happening?

Salama: Well, a little bit of both. To be fair, the world’s eyes were definitely watching. But there was also an element of chaos, just how quickly the event came together, you know, these leaders flying in on short notice. The White House loves protocol. It loves to have days and months, sometimes, to organize things, to book hotel rooms, and to do all this. I mean, all these leaders, they come with big delegations. You know, the city was basically turned upside down.

And remember, the city was already turned upside down because we were in a so-called state of an emergency because, you know, the National Guard has been rolled out and our police federalized. And so just days prior, we were sort of already in a state of chaos, and then suddenly, you have these world leaders descending upon us on almost no notice. It definitely set the tone for the day.

Rosin: Right. I get it. It’s like a Beyoncé concert on short notice.

Salama: Absolutely.

Rosin: It’s like a huge event, but in a totally mad way.

Anne, so you’re watching this over from Europe. It all came together very quickly. What is the view from Europe as this is all happening?

Applebaum: So just to give you some context, we’re in the middle of August, and in most European countries, this is absolutely the height of summer vacation, and everything is shut. Offices, schools, shops—nobody is doing anything. And the fact that so many heads of state were willing to get on a plane on basically 24 hours’ notice and fly to Washington, I think, tells you how unbelievably alarming the Alaska summit appeared here.

Rosin: Oh. So it’s alarming because we’re thinking it as a sort of, you know: The entourage showed up; they’re supporting Zelensky. That’s amazing. But you’re saying it’s coming out of a fear.

Applebaum: Fear and confusion and a sense that maybe the White House doesn’t really understand the rules of the game.

So what happened in Alaska was that Putin got exactly what he wanted. He was treated as a world leader, as a superpower leader. There were American soldiers kneeling on the tarmac, rolling out the red carpet for him. The American president stood on the red carpet and waved and clapped at him.

He had exactly the treatment that he wanted. He had the TV pictures that he wanted. And he went home having offered nothing and given nothing. He still never said that he wants to end the war. He still never said that he would stop fighting. He’s never said that he recognizes Ukrainian sovereignty. So he has given away nothing.

Rosin: Right.

Applebaum: And Trump, interviewed afterward, said the summit was 10 out of 10, and everything was great. And, you know, now Zelensky is going to Washington, and the instinct was We all need to be there to avoid a repeat of February, and also to explain to the president that the war hasn’t ended yet and we may have a long way to go. I mean, I think what was also alarming was that Trump had begun using Putin’s language, so he dropped this word cease-fire, and he started talking vaguely about peace negotiations.

And this is what Putin wants because peace negotiations mean we can vaguely negotiate and he can keep fighting. Whereas it’s in Europe’s interest and Ukraine’s interest and everybody else’s interest that there be a cease-fire, that the war stop at least for some period of time.

And so he was using Putin’s language, he was playing Putin’s game, and Europeans felt that they better show up.

Rosin: Okay, so they came in with a kind of maternal attitude—like, We have to tell you something; we have to teach you something. There’s something dangerous going on. And did that happen?

What Vivian said was it was giant, but it was also chaotic. And it was hard, honestly, to read the signals coming out of the meeting. So what is the biggest change that you read, coming out?

Applebaum: The biggest change was that they got Trump to talk about security guarantees, even in an unclear way.

And you’re right, by the way, about the chaos. I mean, nobody really knows anything, and it’s not clear whether anything has been decided or anything has changed. But to get Trump to acknowledge that any end to the war or any cease to the fighting, whatever we’re calling it—truce, temporary pause, whatever—is very dangerous because Russia could restart the war at any time. And to prevent that, Europeans want Americans to understand that there has to be something given to Ukraine to prevent the Russians from invading again. So there needs to be some longer term—they’re using the term security guarantees.

I mean, it’s a tricky thing because, actually, Ukraine already has security guarantees from the United States. This was back in 1994. There’s something called the Budapest Memorandum, signed by America, Russia, the U.K., and a couple others, that was meant to guarantee Ukraine’s borders, and so on. So theoretically, it’s something that exists already. It’s just that it was never ratified; it was never a big treaty.

And so now the Europeans got Trump thinking along those lines, and they consider that to have been useful to push him in the direction of understanding that you need a structure to end a war. You don’t end it just by stopping the fighting. You need to have other longer-term solutions.

Rosin: Okay. I understand. This is strange because it’s like, basically, they’re trying to educate him on basic things. You can’t just wave your wand and end a war and say a word cease-fire and roll out the red carpet, and everything is fine. Like, you have to actually do something—you have to attend to the details.

Applebaum: This is not how you end wars. You have low-level meetings. You bring together under neutral negotiators, you discuss what the issues are, and then you have the meeting of the big leaders at the very end.

But this is all being done backwards, and that, I think, is also adding to the chaos. So people have the impression, Something big has been achieved, when actually, we still don’t know whether Russia wants to end the war or not.

Rosin: Right. Understood.

Vivian, the leaders were received differently by Trump this time around, like Zelensky, for example. Can you describe how and why it was significant? And why are you laughing?

Salama: Because Zelensky was actually the only one received by Trump.

Rosin: Oh, I see.

Salama: The other ones were received by his head of protocol, which is pretty unusual as well. He was inside the White House, and his head of protocol went out, one by one, individually welcoming the leaders.

He did have some fanfare for Zelensky. The color guard was out at the White House along the driveway, and he did come out of the West Wing and greet him and do all of that. But there was no official red-carpet welcoming or—you know, there was a military-jet flyover when he welcomed Putin, which is pretty extraordinary.

None of that was there for Zelensky, but he did have a warmer greeting than perhaps we’d anticipated. Also, because of the fact that their February meeting was so explosive, you know, listeners may remember that epic encounter that Zelensky had with Trump in February—

Rosin: And J. D. Vance.

Salama: —and J. D. Vance. And Secretary of State Marco Rubio was there, where the entire Oval Office spray, where the journalists go in. It devolved very quickly into a shouting match because they accused Zelensky of not showing enough gratitude to the United States for its support. And so voices were raised, and it became a very, very awkward event.

You know, going from that to this week’s events, where Zelensky showed up in a suit, for starters, because he was criticized by some pro-Trump supporters and pro-Trump journalists that he was not wearing a suit and that he was disrespecting the American president by doing that. This time he showed up in the same outfit that he wore at the Vatican to the pope’s funeral, which was a black sort of cargo blazer and black pants and a black button-down shirt.

Rosin: So, okay. How to read all this. Is that, first of all, a midway concession on Zelensky’s part, not a full concession? And on Trump’s part, I’m trying to understand what you’re saying about how he greeted the European leaders, because in words, he said, Oh, I’m glad they came. It’s all good. It’s good he has an entourage. But in the room, was there some different signal he was sending to this whole posse of people who showed up?

Salama: So he was with Zelensky already when the Europeans arrived. And so, you know, we have to kind of forgive him for not going out and saying hello and greeting the European leaders individually. As far as Zelensky making concessions, yes, he had to make a lot of concessions this time around because of the fact that that first encounter, in February, went so badly that even European leaders afterwards really took Zelensky aside and gave him a talking to, in terms of the way that you manage Donald Trump. And to do so, you cannot engage him.

Rosin: Yeah.

Salama: And Zelensky did engage him that time around. He did kind of try to put up a fight, and they told him that that’s not gonna be a winning battle, that Ukraine needs the United States more than the United States needs Ukraine at this point, and he has to go in there and play the game. And so he did this time around. Obviously, the substance coming out of it, you know, was significant as a result. Whether or not it results in anything, you know, it remains to be seen.

But Anne talked about security guarantees. That definitely is a huge game changer for Trump in terms of his, even, political stance. I covered the campaign last year, and this was a huge issue. Trump repeatedly said on the campaign trail, We’re done with supporting foreign wars. And just to allude to the fact that we are going to have security guarantees, that the U.S. will support Ukraine moving forward, that really goes far from anything that he had ever promised on the campaign trail.

Rosin: So it is real? I mean, that is real.

Salama: They’re looking at it, and Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt yesterday—so that was Tuesday—she went to the podium and said that the president was even considering having U.S. pilots be part of those security guarantees. That’s extraordinary and such a huge departure from what he was saying on the campaign trail, where he was like, Enough with the weapons. Enough with the money. We’re done with these wars.

[Music]

Rosin: When we’re back: Donald Trump’s changing opinion of Vladimir Putin, and whether that offers hope for Ukraine. That’s in a moment.

[Break]

Rosin: Vivian, since Trump’s been elected, he seems to change his views about Putin. Like, he’s warm to Putin, but then Putin does something that frustrates him. Where is he now in his views on Putin?

Salama: We’ve seen a pretty remarkable evolution in the way that Trump has, at least in his public comments, regarded and viewed Putin. Also, his advisers tell me that he has changed his tune, so to speak.

Rosin: Changed his tune—like, understood who Putin is and what he’s about?

Salama: At least has become a little more skeptical of Putin. Whereas, you know, in the first administration, he was really open to hearing Putin out, being influenced by Putin.

You know, I remember in the early days of his first administration, one of his top advisers explained this scene to me where Putin, in a very soft-spoken, almost mumbling voice, lectured Trump about, you know, Kyivan Rus history dating back to the 11th century, and just to explain to him that Ukraine is part of Russia and always should be. And Trump sort of listened intently and absorbed a lot of what Putin was saying to him.

That coupled with a few other instances during his first administration: the sort of, what he calls, the “Russia-, Russia-, Russiagate” of the investigation by the special counsel into influences of the Russian government on the Trump campaign. And then you had the first impeachment, where, you know, the so-called perfect call with Zelensky, when Zelensky was first elected as president, that led to Trump’s first impeachment because he had asked him to do favors against his political opponents. All of that sort of played into his mind of Russia as a great nation led by a powerful man and Ukraine as a corrupt, backstabbing nation.

Flash-forward to his second administration, and I think, you know, he had been talking so much during his campaign about, you know, I will get the Ukraine-Russia war solved within 24 hours of being elected president. Well, that didn’t happen. And obviously, we know governing is a lot harder than campaigning, and so he learned very quickly that this was going to be a complicated matter.

But what ended up happening is that Putin didn’t sort of pick up the phone and rush to call Trump, either to congratulate him or anything else, when he took office, and he started to become very resentful of that, coupled with the fact that when he finally did talk to Putin, Putin was like, I would never harm the Ukrainians. Everything is, you know, it’s fine. I’m never gonna do anything wrong, and I’m gonna stop the bombing, and let’s just talk this out. And then the next day, he would bomb a school. And Trump has actually said repeatedly that, you know, He assures me that he’s not gonna do anything, but then he does, and I don’t really like that.

And so between that and some advisers who are around him, who have really worked hard to make Trump realize that Putin’s not your friend—now, does that mean he likes Zelensky more? Mmm—I don’t know about that. But, you know, he’s at least cautiously dealing with Putin a bit more than we saw in the first Trump administration.

Rosin: Anne, can we get into the tectonic shifts? What the European leaders were afraid of, what we see reforming as this strange new alliance, where the U.S. seemingly sides with Russia against European allies. Coming out of this meeting, how do you see that shift differently, if at all?

Applebaum: It’s not clear to me, honestly, what has really changed. It seems to me that Trump’s instincts are to agree with the last person he spoke to. Most people assumed that he changed his language after Anchorage because of things Putin said to him.

Steve Witkoff very frequently parrots things that sound like they’re coming from Putin as well. So, you know, he’s influenced by them when he talks to them. And he’s influenced by the Ukrainians and the Europeans when he talks to Europeans.

Rosin: Let’s just say: He’s the special envoy to the Middle East.

Applebaum: Yes. Steve Witkoff is the special envoy to Russia and to the Middle East. He’s somebody with no background in diplomacy and no knowledge of Russian or Ukrainian history.

Salama: He’s a real-estate executive.

Rosin: He’s a real-estate executive, yeah.

Applebaum: He’s a real-estate executive who, as I said, frequently repeats things that clearly come from Putin or from people around Putin. And it often looks like what Trump is doing is seeking to emerge as the winner from whatever situation he’s in. Whether he’s in Anchorage or whether he’s in Washington, it’s important that he dominate the scene and that he run the show. I am not sure that he has a deeper strategy.

Rosin: You wrote after his meeting with Putin in Alaska that Trump has no cards in that situation. And you explained that, I think, in this conversation, the ways in which Putin emerged the winner from that. Do you think that’s changed? Like, did Trump come out of this meeting with Zelensky with some cards or some things to play against Putin? Like, the security guarantees, for example.

Applebaum: Maybe. I mean, the point is that—really, almost unnoticed—Trump has been dismantling American sanctions on Russia. These are commercial sanctions that require constant updating. This administration hasn’t been updating them. He’s been cutting or seeking to cut funding for the Russian-language media that the U.S. has supported for many decades. He’s twice cut military aid to Ukraine. There have been many negative gestures towards Zelensky, and so on, that we’ve already talked about.

The Russians see all of that, and they understand it all as a package of Trump reducing his ability to play in the situation, reducing his influence, and so on. So when I say he has no cards, it doesn’t mean that the United States can’t do anything. It means that Trump has been reducing what he’s able to do. And if everybody else sees that—the Europeans see it, you know, Russians obviously see it, Ukrainians obviously see it. I don’t know that Americans see it, but everybody else does.

Rosin: Yeah. It’s difficult to read, because on the one hand, you’re describing a systematic shift in negotiating position. But on the other hand, the fact that he changes given any meeting means that kind of is a card. It’s like I can have a meeting with Zelensky and the European leaders, and I can completely shift my position and talk about security guarantees, and then that’s my card. You know, he’s a little unpredictable.

Applebaum: Talking about European security guarantees gives the Russians something new to be nervous about.

Rosin: Right.

Applebaum: Remember, for them, you know, their assumption, I think right now we can safely say, is that they still think they’re gonna win the war.

Rosin: The Russians?

Applebaum: The Russians.

Rosin: Well, they are winning the war, aren’t they?

Applebaum: Hmmm—no. They’re not winning. They’re not losing, but they’re not winning. You know, at the current rate of fighting, they will conquer the rest of Donbas in four years.

Rosin: Four years.

Applebaum: So they’re, you know, putting a lot of pressure on Ukraine, but they’re not winning very fast. But their assumption is that they will win because the U.S. will withdraw its support, and Europe will get tired, and Ukrainians will get tired, and so on. So they’re still operating on that assumption. And the way that we change their minds and convince them that they’re not winning is precisely by saying, No, actually we’re gonna add more. We’re gonna do not just security guarantees, but we’re gonna do new sanctions, we’re gonna do new aid for Ukraine, we’re gonna change the rules again, we’re gonna do a big shake-up.

And to be fair, there are people in Washington who understand that. And actually there are a number of Republican and Democratic senators who’ve been trying to push the U.S. in that direction for a long time. And, you know, this war is over when the Russians understand that they can’t win. And for the last six months, we’ve been giving them the impression that they still can win. So we need to change that calculus.

And as I said, Europeans understand that. That’s why they were in Washington. The Senate understands that. That’s why there’s a Senate bill on the table to do that. Not clear whether Trump understands that or not.

Rosin: I see. So the important thing is what you just said, giving Putin the impression that he cannot win the war. That, to you, is the important card to play. That’s the important pressure to keep on Russia, in whatever way that happens.

Applebaum: Yes.

Rosin: Got it.

Applebaum: Yes, and Alaska was a step in the opposite direction.

Rosin: So, Vivian, what kind of peace deals are under discussion? Besides the security guarantees, did you get a realistic sense in Washington what is possible at this moment? There’s pressure from Senators. There’s Trump who’s unpredictable. What seemed doable?

Salama: Well, one of the things on the Sunday shows after the Putin summit, but before the Europeans came to town, was this notion of concessions. Both Steve Witkoff, who we were just talking about, and Secretary of State Marco Rubio were out there, talking about the fact that when you have a negotiation and you want to reach a compromise, both sides have something to gain and have something to lose, and that’s just inevitable.

And that’s the kind of talk that makes the Europeans very nervous, certainly Ukraine. Where Ukraine wanted to go, not just—you know, Washington often talks about the February 2022 borders, the territory that was taken by Russia after February 2022, when it launched this full-scale invasion.

But in the Ukrainians’ mind, they’ve been fighting for their territory since 2014. They’re talking about Crimea and the contested parts of eastern Ukraine that have been under stress long before 2022. And so they believe that not only should they regain that territory back, they fight for Crimea too.

And Washington has tried to kind of settle Ukraine’s mind and say, you know—and even during the Biden era, where they say—Let’s just talk about February 2022 borders, or you might lose Crimea. Let’s see how it goes. But at least we’re gonna try to fight for eastern Ukraine. The Trump administration kind of talks more in terms of freezes, where they say, Territory that was lost after February 2022, you’re gonna have to cut your losses.

And that is something that not only the Ukrainians believe is a nonstarter, but that the rest of Europe sees as very alarming because they believe that that kind of concession will just embolden Putin, where he says, Okay, this was a victory now. Let’s play along, and we could regroup and kind of expand our gains.

Rosin: So everything you just said sounds like a recipe for not agreement.

Salama: It is so hard to imagine Ukraine accepting anything less than at least the borders before February 2022. And that would be really twisting their arms.

And remember, for Russia—for Putin in particular—this is not about just a little bit of territory in eastern Ukraine. This is existential in Putin’s mind for the future of Russia. He believes Ukraine does not have the right to exist. He believes it is part of greater Russia and they have to regain it as part of that legacy.

And so for him, he will stop at nothing to regain that. Whether it’s, you know, play along now and then revisit the war later, you know, that remains to be seen. And so there is a concern, especially across Europe, European officials I speak with, about this naivete within the Trump administration, where they’re so eager to cut a deal, but in doing so, you’re redrawing the map of Europe and emboldening Putin. And so that is something that the Europeans, certainly—it was a big reason why they jumped on that plane on 24 hours’ notice, not only to help Zelensky kind of avoid a catastrophic meeting, like the one in February, but also to moderate Trump’s whims and say, you know, Yeah, we want a deal, but we want a deal that ensures the security and, you know, the sanctity of Ukraine.

Applebaum: You know, it’s also really important to understand that Putin has not offered to concede anything. He’s not giving back territory that he’s conquered. And more than that, he’s demanding territory that he can’t conquer, that he hasn’t been able to conquer—in fact, that he hasn’t been able to conquer since 2014. And this is the rest of this Donbas province. So he’s offering nothing.

And I think the second point to make that’s very important is that this is not a war over territory. Russia does not need more territory. This is a war to damage and undermine the sovereignty and legitimacy of the Ukrainian state as a prelude to undermining it and eventually taking it over or making it into some kind of state that’s reliant on Russia.

And the Russians are also perfectly happy to try doing that again through other kinds of pressure. You know, maybe they could end the war on unfavorable terms for Ukraine, then try to unseat Zelensky, then try to use propaganda to convince Ukrainians they were robbed. I mean, there’s a whole kind of sequence of events that could follow.

So the point is that until they have given up that goal—you know, the goal of destroying Ukraine as a sovereign nation—then the war is not over. And to pretend that it’s over is very dangerous.

Rosin: That’s complicated. Those are old Soviet dreams. I mean, basically, he wants the relationship he had with Estonia and so many other, you know, territories. How do you make somebody give up that? Like, how do you break someone of that goal?

Applebaum: I remain convinced that the only way to do it is to persuade him that he can’t win—it can’t be done, that Ukraine is too strong, its alliances are too powerful.

Rosin: Got it.

Salama: I mean, just to emphasize: I don’t think you can break that mentality. I mean, just to show you as an example, Sergey Lavrov, the foreign minister of Russia, arrived in Alaska last week wearing a sweatshirt that said C.C.C.P. on it, which is the Soviet Union, U.S.S.R. They are still living in that era, very much so. And some of it is mind games, obviously, but a lot of it is also just this nostalgia for that era.

Rosin: Right.

Salama: Can I just add one more thing here, because we were talking about this earlier? I spent most of 2022 on the front lines in Ukraine, and I gotta tell you, the one thing I heard over and over again was that they believe that Putin has more stamina than the entire West combined, that the West will eventually move on, whether for politics, whether for economic reasons, whether because they just can’t sustain all this aid, military and economic aid to Ukraine. But Putin is playing for the long game, and they knew that in Ukraine.

I mean, this is a former part of the Soviet Union. The Russians are not strangers to them. They know the Russians better than any of us, and they know that Putin is just waiting for the West to get tired.

Rosin: Interesting. So it’s almost like they saw this moment coming, and that actually brings more significance to the fact that the European leaders showed up. It’s like, Wait—we’re actually not out of patience yet. Like, We can be ripped from our vacations and show up for you on short notice.

Salama: Yes. And it’s also why Zelensky has to hustle so hard, because he does not want the West to forget about his country.

Rosin: Yeah. Okay, so you guys have described a lot of complicated mechanics that need to happen in order to bring this to a good place. We seem very far away from it, and Trump seems very far from understanding all of these dynamics that you just described.

So what happens now? I mean, Trump said repeatedly at the Monday summit that he wants a joint meeting between him, Zelensky, and Putin, and that’s what needs to happen. Is that realistic? How likely is that?

Salama: They are cautiously optimistic at the White House that this is gonna work out. The Kremlin has already suggested it won’t, so I don’t really know where we go from here. On Tuesday, the press secretary said that, you know, the wheels are in motion to try to get Putin and Zelensky to sit down together,

And then, obviously, this broader summit—Zelensky seems game, but you know, it takes two to tango in this case. It would be pretty extraordinary if it happens. Gosh, I will camp out for days just to be a fly on that wall. But not a lot of people are very optimistic that that’s gonna happen.

Rosin: All right, well if it does, we will have you both back on. Thank you for joining me today and helping us understand what happened.

Salama: Thanks for having me.

Applebaum: Thank you.

[Music]

Rosin: This episode of Radio Atlantic was produced by Rosie Hughes. It was edited by Kevin Townsend. Rob Smierciak engineered and provided original music. And Sam Fentress fact-checked. Claudine Ebeid is the executive producer of Atlantic audio, and Andrea Valdez is our managing editor.

Listeners, if you like what you hear on Radio Atlantic, you can support our work and the work of all Atlantic journalists when you subscribe to The Atlantic at TheAtlantic.com/Listener.

I’m Hanna Rosin. Thanks for listening.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

Mahmoud Sleem / Anadolu / GettyAn aerial view of the destruction, taken after the ceasefire agreement came into effect in the Gaza Strip on January 21, 2025.

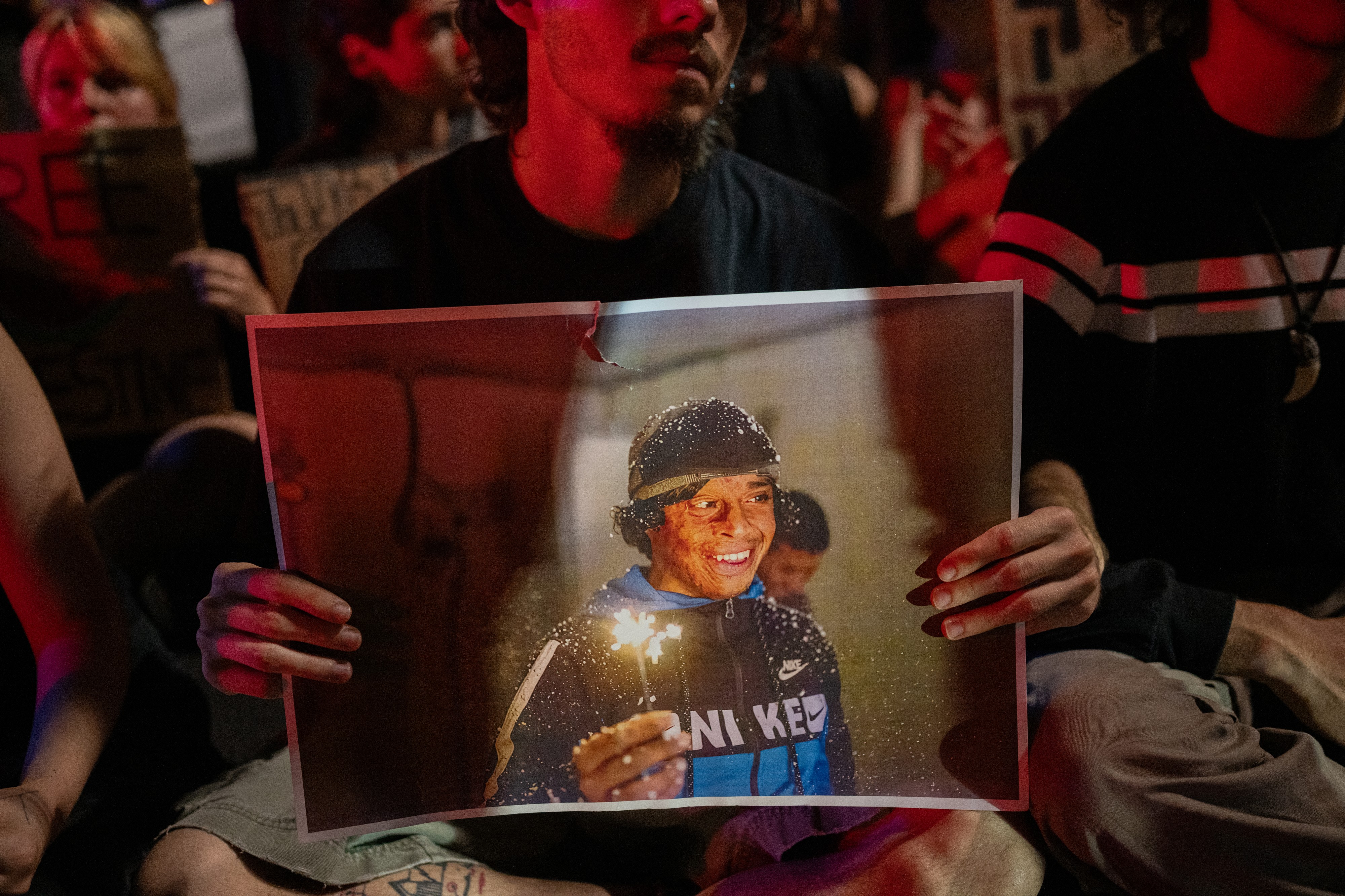

Mahmoud Sleem / Anadolu / GettyAn aerial view of the destruction, taken after the ceasefire agreement came into effect in the Gaza Strip on January 21, 2025. Tamir Kalifa / GettyA demonstrator holds a photo of Palestinian activist Odeh Hathalin during a protest over his death, on August 3, 2025 in Tel Aviv, Israel.

Tamir Kalifa / GettyA demonstrator holds a photo of Palestinian activist Odeh Hathalin during a protest over his death, on August 3, 2025 in Tel Aviv, Israel. Kevin Frayer / GettySoldiers from the People’s Liberation Army stand in formation as they practice for an upcoming military parade to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II and Japan’s surrender, at a military base in Beijing, China, on August 20, 2025.

Kevin Frayer / GettySoldiers from the People’s Liberation Army stand in formation as they practice for an upcoming military parade to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II and Japan’s surrender, at a military base in Beijing, China, on August 20, 2025. Achmad Ibrahim / APA dove perches on the hat of an Indonesian army soldier during a flag-raising ceremony marking the 80th anniversary of the country’s independence, at Merdeka Palace in Jakarta, Indonesia, on August 17, 2025.

Achmad Ibrahim / APA dove perches on the hat of an Indonesian army soldier during a flag-raising ceremony marking the 80th anniversary of the country’s independence, at Merdeka Palace in Jakarta, Indonesia, on August 17, 2025. Michael Probst / APA heron takes off from a dung hill in Frankfurt, Germany, on August 18, 2025.

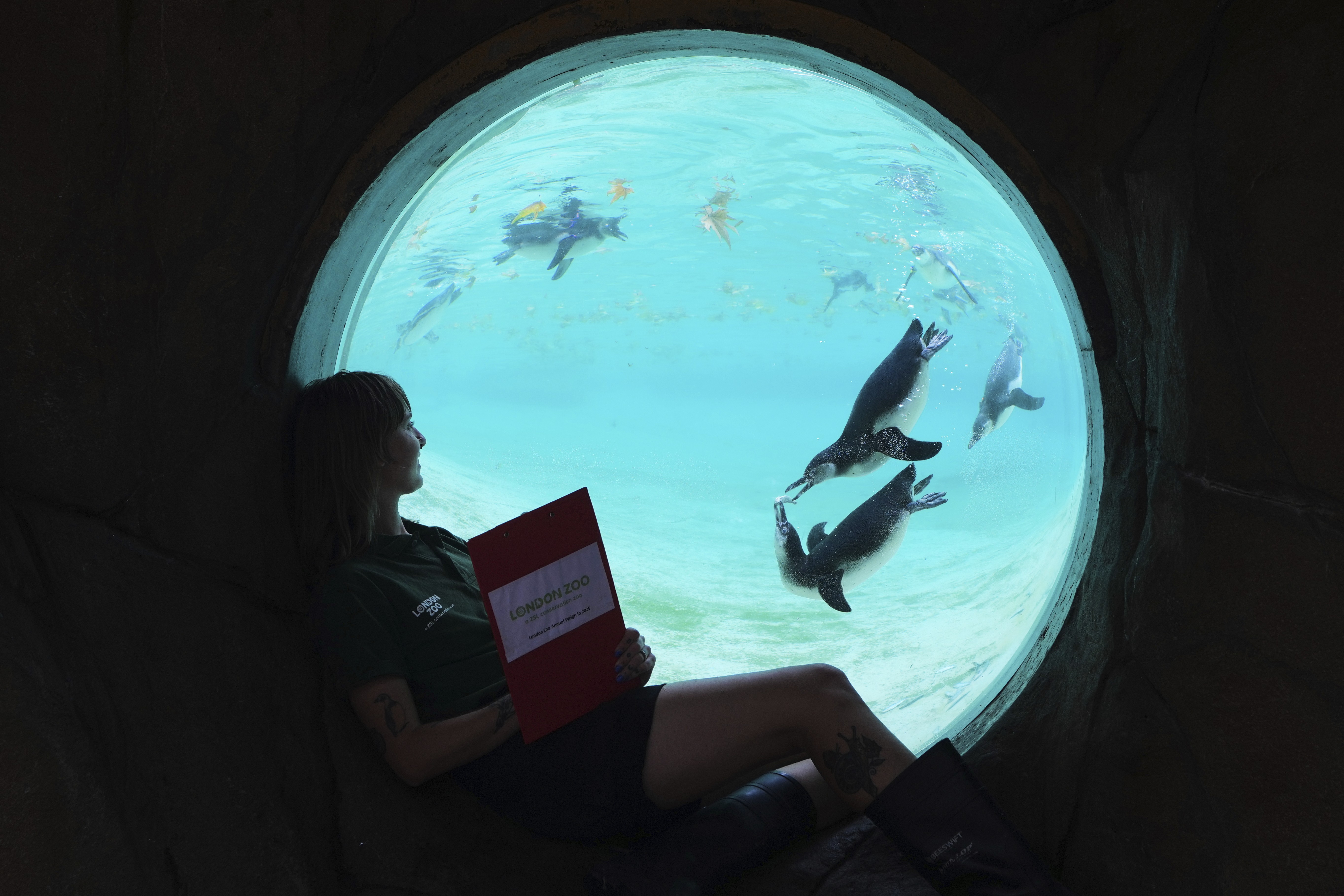

Michael Probst / APA heron takes off from a dung hill in Frankfurt, Germany, on August 18, 2025. Kirsty Wigglesworth / APThe keeper Jessica Ray watches Humboldt penguins as the London Zoo records animals’ vital statistics at an annual weigh-in as a way of monitoring their health and development, and even identifying pregnancies, in London, England, on August 19, 2025.

Kirsty Wigglesworth / APThe keeper Jessica Ray watches Humboldt penguins as the London Zoo records animals’ vital statistics at an annual weigh-in as a way of monitoring their health and development, and even identifying pregnancies, in London, England, on August 19, 2025. Gallo Images / Orbital Horizon / Copernicus Sentinel Data 2025 / GettyA satellite view of Hurricane Erin in the Atlantic Ocean, on August 18, 2025.

Gallo Images / Orbital Horizon / Copernicus Sentinel Data 2025 / GettyA satellite view of Hurricane Erin in the Atlantic Ocean, on August 18, 2025. Lisi Niesner / ReutersChina’s Royal performs during the B-girls’ gold-medal breakdance match at the 2025 World Games, in Chengdu, China, on August 17, 2025.

Lisi Niesner / ReutersChina’s Royal performs during the B-girls’ gold-medal breakdance match at the 2025 World Games, in Chengdu, China, on August 17, 2025. Gold & Goose Photography / GettyMarc Marquez rides during a qualifier for the MotoGP of Austria, at Red Bull Ring in Spielberg, Austria, on August 16, 2025.

Gold & Goose Photography / GettyMarc Marquez rides during a qualifier for the MotoGP of Austria, at Red Bull Ring in Spielberg, Austria, on August 16, 2025. Denis Poroy / Imagn Images / ReutersA security guard tackles a fan who ran onto the field during a baseball game between the San Francisco Giants and the San Diego Padres, at Petco Park in San Diego, California, on August 19, 2025.

Denis Poroy / Imagn Images / ReutersA security guard tackles a fan who ran onto the field during a baseball game between the San Francisco Giants and the San Diego Padres, at Petco Park in San Diego, California, on August 19, 2025. Liu Jianmin / VCG / GettyA person in a dinosaur costume entertains the crowd and cheers for players prior to a Jiangsu Football City League match between Changzhou and Zhenjiang, in Changzhou, Jiangsu province, China, on August 16, 2025.

Liu Jianmin / VCG / GettyA person in a dinosaur costume entertains the crowd and cheers for players prior to a Jiangsu Football City League match between Changzhou and Zhenjiang, in Changzhou, Jiangsu province, China, on August 16, 2025. Focke Strangmann / AFP / GettyA harness racer prepares for a race of the Duhner Wattrennen horse race, with a container ship in the distance, in Cuxhaven, Germany, on August 17, 2025.

Focke Strangmann / AFP / GettyA harness racer prepares for a race of the Duhner Wattrennen horse race, with a container ship in the distance, in Cuxhaven, Germany, on August 17, 2025. Spasiyana Sergieva / ReutersFollowers of the Universal White Brotherhood, an esoteric society that combines Christianity and Indian mysticism set up by the Bulgarian Peter Deunov, perform a dance-like ritual called “paneurhythmy,” in Rila Mountain, Bulgaria, on August 19, 2025.

Spasiyana Sergieva / ReutersFollowers of the Universal White Brotherhood, an esoteric society that combines Christianity and Indian mysticism set up by the Bulgarian Peter Deunov, perform a dance-like ritual called “paneurhythmy,” in Rila Mountain, Bulgaria, on August 19, 2025. Cesar Manso / AFP / GettyA wildfire burns in Castrillo de Cabrera, Spain, on August 16, 2025. Spain, now in its third week under a heat-wave alert, is still battling wildfires raging in the northwest and west of the country, where the army has been deployed to help contain the blazes.

Cesar Manso / AFP / GettyA wildfire burns in Castrillo de Cabrera, Spain, on August 16, 2025. Spain, now in its third week under a heat-wave alert, is still battling wildfires raging in the northwest and west of the country, where the army has been deployed to help contain the blazes. Pedro Nunes / ReutersA car burns during a wildfire in Meda, Portugal, on August 15, 2025.

Pedro Nunes / ReutersA car burns during a wildfire in Meda, Portugal, on August 15, 2025. Florion Goga / ReutersA person treats a burned horse in an animal shelter after a wildfire, in Tirana, Albania, on August 15, 2025.

Florion Goga / ReutersA person treats a burned horse in an animal shelter after a wildfire, in Tirana, Albania, on August 15, 2025. Kirsty Wigglesworth / APThe keeper Poppy Jewell weighs a capybara during the London Zoo’s annual weigh-in, on August 19, 2025.

Kirsty Wigglesworth / APThe keeper Poppy Jewell weighs a capybara during the London Zoo’s annual weigh-in, on August 19, 2025. Jorge Silva / ReutersA person poses during the “walk for Exu,” an event for followers of the Afro-Brazilian religions Candomble and Umbanda, in São Paulo, Brazil, on August 17, 2025.

Jorge Silva / ReutersA person poses during the “walk for Exu,” an event for followers of the Afro-Brazilian religions Candomble and Umbanda, in São Paulo, Brazil, on August 17, 2025. Andy Wong / APPassengers take escalators to a subway station as they arrive in Chaoyang Railway Station, in Beijing, China, on August 18, 2025.

Andy Wong / APPassengers take escalators to a subway station as they arrive in Chaoyang Railway Station, in Beijing, China, on August 18, 2025. Robin Van Lonkhuijsen / ANP / AFP / GettyShips and boats gather in a sail-in parade during the 50th edition of the Sail Amsterdam festival, in Amsterdam, on August 20, 2025.

Robin Van Lonkhuijsen / ANP / AFP / GettyShips and boats gather in a sail-in parade during the 50th edition of the Sail Amsterdam festival, in Amsterdam, on August 20, 2025. Indranil Mukherjee / AFP / GettyPeople throw water on Hindu devotees forming a human pyramid during Krishna Janmashtami, a festival that marks the birth of Krishna, in Mumbai, India, on August 16, 2025.

Indranil Mukherjee / AFP / GettyPeople throw water on Hindu devotees forming a human pyramid during Krishna Janmashtami, a festival that marks the birth of Krishna, in Mumbai, India, on August 16, 2025. Charly Triballeau / AFP / GettyA woman and her child arrive at a hearing, as federal agents patrol the hallways outside of a courtroom at New York Federal Plaza Immigration Court at the Jacob K. Javitz Federal Building, in New York City, on August 20, 2025.

Charly Triballeau / AFP / GettyA woman and her child arrive at a hearing, as federal agents patrol the hallways outside of a courtroom at New York Federal Plaza Immigration Court at the Jacob K. Javitz Federal Building, in New York City, on August 20, 2025. Pierre Crom / GettyMembers of Ukraine’s Armed Forces 18th Sloviansk Brigade anti-drone unit work to intercept Russian drones in the Donetsk region of Ukraine, on August 20, 2025.

Pierre Crom / GettyMembers of Ukraine’s Armed Forces 18th Sloviansk Brigade anti-drone unit work to intercept Russian drones in the Donetsk region of Ukraine, on August 20, 2025. Deepak Turbhekar / APFire officials rescue passengers from a monorail after it stalled due to overcrowding, which caused an electrical outage, in Mumbai, India, on August 19, 2025.

Deepak Turbhekar / APFire officials rescue passengers from a monorail after it stalled due to overcrowding, which caused an electrical outage, in Mumbai, India, on August 19, 2025. Mark Schiefelbein / APThe northern lights glow in the night sky near Yellowknife, in Canada's Northwest Territories, on August 20, 2025.

Mark Schiefelbein / APThe northern lights glow in the night sky near Yellowknife, in Canada's Northwest Territories, on August 20, 2025. Mikel Konate / ReutersA pyrocumulus cloud forms as wildfire smoke rises above a cemetery, in the village of Vilarmel, Lugo area, Galicia region, Spain, on August 16, 2025.

Mikel Konate / ReutersA pyrocumulus cloud forms as wildfire smoke rises above a cemetery, in the village of Vilarmel, Lugo area, Galicia region, Spain, on August 16, 2025. Bashar Taleb / AFP / GettyPalestinians rush for cover as debris flies after an Israeli strike hits a building in Jabalia, in the northern Gaza Strip, on August 20, 2025.

Bashar Taleb / AFP / GettyPalestinians rush for cover as debris flies after an Israeli strike hits a building in Jabalia, in the northern Gaza Strip, on August 20, 2025. Ramadan Abed / ReutersAid packages, dropped from an airplane, descend over Gaza, in Deir Al-Balah, in the central Gaza Strip, on August 19, 2025.

Ramadan Abed / ReutersAid packages, dropped from an airplane, descend over Gaza, in Deir Al-Balah, in the central Gaza Strip, on August 19, 2025. Ulet Ifansasti / GettyMembers of a Yogyakarta classic-bicycle group pose with horses after taking part in a ceremonial event to mark the 80th Indonesian Independence Day, on August 17, 2025, in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Ulet Ifansasti / GettyMembers of a Yogyakarta classic-bicycle group pose with horses after taking part in a ceremonial event to mark the 80th Indonesian Independence Day, on August 17, 2025, in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Mindaugas Kulbis / APA man mows a meadow near the town of Ignalina, Lithuania, on August 20, 2025.

Mindaugas Kulbis / APA man mows a meadow near the town of Ignalina, Lithuania, on August 20, 2025. Sydney Krantz for The AtlanticAt a capped landfill in the Meadowlands, dense stands of phragmites and Spartina grasses overlook the Hackensack River.

Sydney Krantz for The AtlanticAt a capped landfill in the Meadowlands, dense stands of phragmites and Spartina grasses overlook the Hackensack River. Sydney Krantz for The AtlanticA netted barrier stands alongside wetlands in the Meadowlands, limiting erosion and protecting adjacent waterways.

Sydney Krantz for The AtlanticA netted barrier stands alongside wetlands in the Meadowlands, limiting erosion and protecting adjacent waterways. Sydney Krantz for The AtlanticA great blue heron wades in the waters of Mill Creek Marsh in Secaucus, New Jersey.

Sydney Krantz for The AtlanticA great blue heron wades in the waters of Mill Creek Marsh in Secaucus, New Jersey. Sydney Krantz for The AtlanticTom Marturano walks a trail at Mill Creek Point Park.

Sydney Krantz for The AtlanticTom Marturano walks a trail at Mill Creek Point Park. Illustration by Summer Lien for The Atlantic

Illustration by Summer Lien for The Atlantic Gabriela Pesqueira / The Atlantic

Gabriela Pesqueira / The Atlantic Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyAn aerial view shows the wooden Kiruna Church being transferred to its new location, in Kiruna, Sweden, on August 19, 2025. The church is being moved five kilometers (three miles) to the new town center of Kiruna, because of the expansion of the nearby iron-ore mine operated by the state-owned Swedish mining company LKAB.

Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyAn aerial view shows the wooden Kiruna Church being transferred to its new location, in Kiruna, Sweden, on August 19, 2025. The church is being moved five kilometers (three miles) to the new town center of Kiruna, because of the expansion of the nearby iron-ore mine operated by the state-owned Swedish mining company LKAB. Malin Haarala / APVicar Lena Tjarnberg (left) and Bishop Asa Nystrom bless Kiruna Church, called Kiruna Kyrka in Swedish, on August 19, 2025, shortly before it was moved as part of the town’s relocation.

Malin Haarala / APVicar Lena Tjarnberg (left) and Bishop Asa Nystrom bless Kiruna Church, called Kiruna Kyrka in Swedish, on August 19, 2025, shortly before it was moved as part of the town’s relocation. Mauro Ujetto / NurPhoto / GettyKiruna Church, standing 131 feet (40 meters) tall, sits ready for relocation.

Mauro Ujetto / NurPhoto / GettyKiruna Church, standing 131 feet (40 meters) tall, sits ready for relocation. Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettySelf-propelled modular transporters were used to carry the 670-ton church and support beams on a total of 224 wheels.

Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettySelf-propelled modular transporters were used to carry the 670-ton church and support beams on a total of 224 wheels. Leonhard Foeger / ReutersKees Breedveld, a site manager with Mammoet, the company carrying out the move, displays the remote-control panel used to operate the transporters on August 18, 2025.

Leonhard Foeger / ReutersKees Breedveld, a site manager with Mammoet, the company carrying out the move, displays the remote-control panel used to operate the transporters on August 18, 2025. Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyPeople gather to watch the moving of Kiruna Church on August 19, 2025.

Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyPeople gather to watch the moving of Kiruna Church on August 19, 2025. Fredrik Sandberg / TT News Agency / AFP / GettyPeople watch from the road and rooftops as Kiruna Church drives by.

Fredrik Sandberg / TT News Agency / AFP / GettyPeople watch from the road and rooftops as Kiruna Church drives by. Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyWorkers escort the church on its journey.

Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyWorkers escort the church on its journey. Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyKiruna Church, seen from above on its two-day journey to its new location, covering three miles (five kilometers).

Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyKiruna Church, seen from above on its two-day journey to its new location, covering three miles (five kilometers). Bernd Lauter / GettyA spectator takes a picture of the church as it passes by on August 19, 2025.

Bernd Lauter / GettyA spectator takes a picture of the church as it passes by on August 19, 2025. Fredrik Sandberg / TT News Agency / AFP / GettyPeople watch as the church slowly navigates a tight corner.

Fredrik Sandberg / TT News Agency / AFP / GettyPeople watch as the church slowly navigates a tight corner. Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyPeople gather to watch as the church passes through part of the town.

Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyPeople gather to watch as the church passes through part of the town. Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyAn aerial view of Kiruna Church arriving at its final location in the new city center on August 20, 2025.

Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyAn aerial view of Kiruna Church arriving at its final location in the new city center on August 20, 2025. Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyLocals and visitors look up at the church, situated in its new location after a two-day move, in Kiruna, Sweden, on August 20, 2025.

Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / GettyLocals and visitors look up at the church, situated in its new location after a two-day move, in Kiruna, Sweden, on August 20, 2025. Takako Kido for The Atlantic

Takako Kido for The Atlantic Larry Towell / Magnum

Larry Towell / Magnum