I love driving. I know driving is kind of evil. But I love it. I love my stupid little car—a 2015 Volkswagen Golf TDI. It’s diesel. It gets 45 miles per gallon. It’s a 6-speed stick shift. It was cheap (due to Volkswagen recalling every diesel they sold after being caught doing really evil stuff to cheat the emissions standards of the U.S., and then needing to offload all those cars) and it goes fast and is tiny and I love zipping around country corners and pretending I’m a racecar driver (while remaining at a reasonable speed, of course; I would never break the law). Vroom vroom.

But over the last few years, driving has become a much more miserable experience for me. I hope not to negate my own responsibility here, but, I think, it’s not that I’ve changed, it’s that everything else has: every car around me is suddenly humongous, all of their headlights seem designed to blind me and cause me to crash into a telephone poll, and, worst of all, the people behind the wheel of these humongous and bright cars seem to actively want to kill me, and, presumably, everyone else on the road too.

People seem to agree that drivers have gotten worse in the last few years, that headlights have gotten too bright, and that cars have gotten too big and dangerous. And yet, many, many people keep buying these huge, dumb cars, despite the fact that they cost way too much money. The average car price is now $47,000. That is, frankly, insane.

Perhaps the pandemic made people worse at driving and more prone to antisocial behavior; perhaps some people are affected by Long Covid and cannot think as clearly as they barrel down the road. Perhaps people are more stressed and depressed and taking that out on everyone.

All those things are probably true. But I think they’re also all related—they sit under the umbrella of a culture designed to atomize us into machines indifferent to (or even actively seeking pleasure in) death and destruction. Cars and driving are not the cause of this problem; rather they are the most effective tool to enact a purposeful societal violence. Which is what, in many ways, they’ve always been. We’ve simply made those tools much more effective at doing their jobs recently. If we have any hope of challenging our ever-more-insane car culture, we first must correctly identify the problem.

As the United States has grown ever-more reliant on cars, there’s been a growing counter-movement. Young people seem to want cars less these days; they prefer living in cities with public transit. Organizations that promote things like adding bike lanes and redesigning streets to make them less car-centric have sprouted up in nearly every midsize and large American city. And while these movements are commendable, they’re not very successful: America’s streets are more dangerous for pedestrians now than they’ve been in 40 years. The number of pedestrians killed by cars has increased by 77 percent (!!!) just since 2010.

How can it be that fewer people value cars and driving at the same time that our culture becomes more car-centric and less pedestrian friendly? It’s probably because we’ve mis-identified the source of the issue at hand. Saying cars are the root of America’s social rot is like saying missiles are the cause of war. Violence is the point of war, not an unintended consequence; and missiles are the tool through which that violence is carried out. And violence is the point of our transportation system in the United States; and cars are the tool through which that violence is carried out.

We often hear the story that the interstate highway system was constructed without regard for urban communities, especially Black communities—that the suburbs and their attendant roads were made for white people and that the destruction of cities and the wealth and culture they contained was an unnecessary and evil consequence of that creation. But that’s not really what happened. Our car culture was built by our government with the explicit intent to isolate people from one another; the objective was to destroy community.

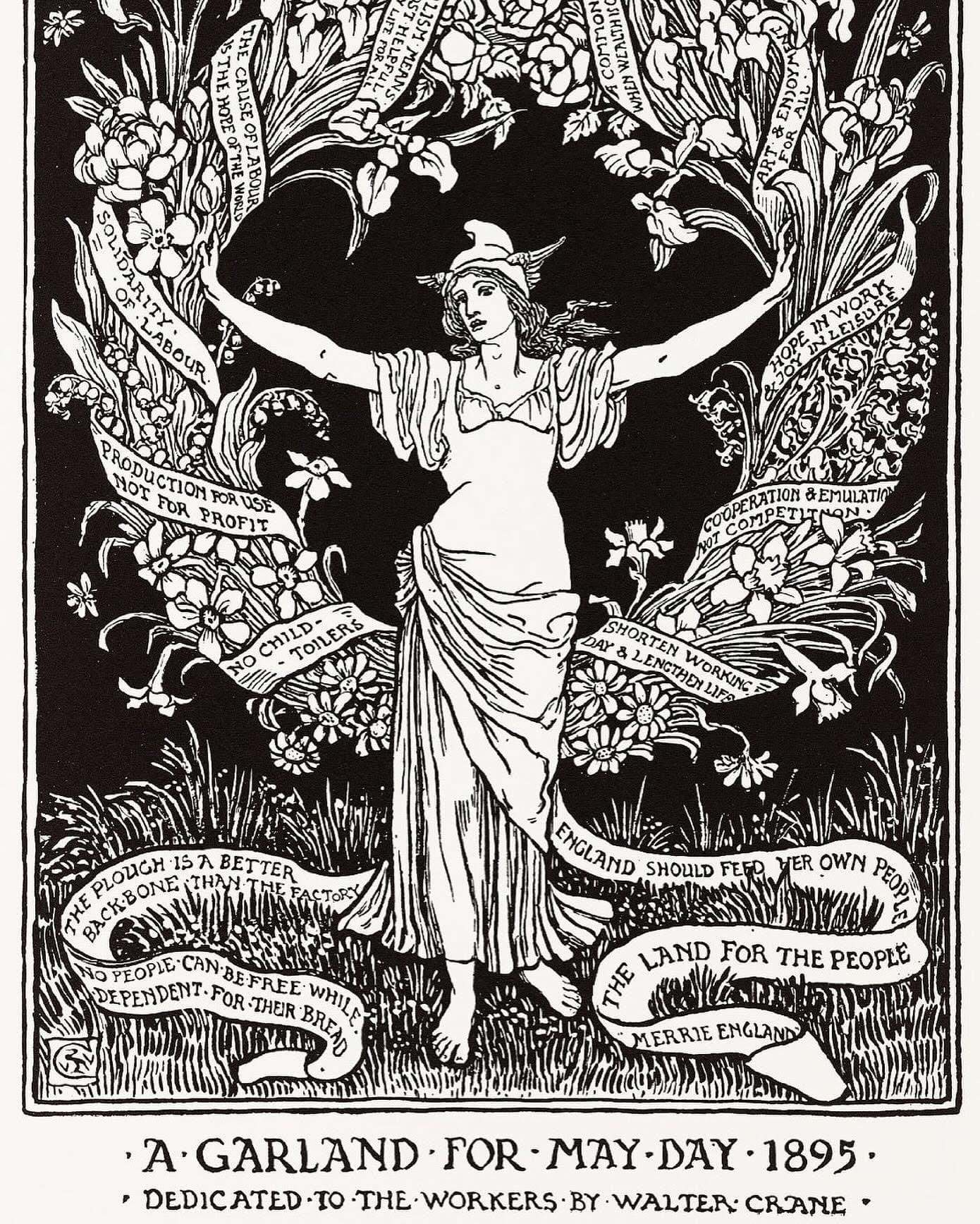

As I wrote in my book How to Kill a City, the suburbs were envisioned as a way to break solidarity. In the 1940s, there were growing movements (gay, feminist, cross-racial, anti-capitalist, pro-union, etc.) in American cities. The suburbs helped solve that problem with a carrot and stick.

White people got the carrot (surprise surprise)—they were gifted very cheap land and mortgages and cars and the wealth that those things created in exchange for their politics and communities and identities. “No man who owns his house and lot can be a communist,” William J. Levitt, the creator of the prototypical suburb Levittown said. “He has too much to do.”

And People of Color got the stick—their communities and wealth and the brewing radicalism within those communities were all destroyed by the highways rammed through them. Which, again, was not an unintended consequence, but the exact point. Joseph Mccarthy (of the McCarthy era and many other bad things), actually got his start as a shithead by linking urbanism and multifamily housing to communism, and encouraging the destruction of all of those things to prevent the destruction of capitalism.

(As an aside, gentrification functions in a largely similar way to suburbanization in terms of reifying individualist politics and culture: once cities were hollowed out, white people were encouraged to move back into them, but now with suburbanized values, thus further entrenching the geography of individualism (for more on all this, read my book, as well as Sarah Schulman’s The Gentrification of the Mind).

But the question remains: if suburbanization and highways and cars were always tools to reinforce this system of individualism and stratification, then why has driving suddenly gotten so much worse? (And by most accounts it really has: 54 percent of Americans think driving is more miserable now than before the pandemic).

Well, if we can consider the car of the mid-1900s one of the most effective tools/weapons of industrial post-war capitalism, we might now consider the modern car an updated technology for our new-ish era of capitalism. Today it's not so much the physical landscape that needs destroying, but the remaining social bonds that tie us together and the institutions that once fostered those bonds (schools, workplaces, unions, government agencies, etc.).

This is an era of constant competition—steady, full-time work replaced by the gig economy in which we are all fighting each other as independent entities for the same slice of the pie. And that competition can only occur through hyper-individualism. Cars (along with several other powerful technologies, such as, I’d argue, the DSM 😛) are the perfect tool to accomplish this task.

In a really great essay on cars and neoliberalism, Patrick McCarthur, building on the work of psychologist Zygmunt Bauman, argues that our age of capitalism is a “hunter’s utopia” in which a population’s collective ideals of progress are replaced by individualist ideals of survival. Any and all progress is now measured by how good we are at surviving the system in which we are now trapped (and then we call this state of survival mode “freedom”).

“...everyone must continue to hunt to survive, even if they are not really hunters,” McCarthur writes. “Thus, in a neoliberal framework, people have the freedom to be anyone, but the social system carries the assumption that everyone must have the same relative requirements and expectations.”

We’re all free to hunt as we please, but we all must hunt, and we’re all in competition for the same boar, or deer, or whatever (IDK I’ve never hunted). Which creates a kind of arms race—if we must fight each other to survive, we will begin an obsessive search for the perfect tools and strategies to outperform one another (this is starting to sound a lot like The Hunger Games).

And so it’s no surprise that cars have gotten bigger and more dangerous; it’s no coincidence that these bright-ass headlights are made without any regard for other people—because our age of capitalism requires us to be in a constant battle with each other. Who cares if your car kills kids and blinds drivers? That’s the point. Better I survive than you.

All the way back in the year 2000, when SUVs were first becoming popular, automakers essentially admitted this: they told the New York Times that people were no longer wanting to be “other-oriented”and thus no longer wanted to buy cars associated with others (think: families and minivans), and instead were becoming “self-oriented”—less social, and more fearful of crime and society itself. Big, dangerous cars like SUVs became the preferred tools of a completely self-focused era.

In a more recent Times article, citing an AAA survey, the paper pondered how a large percentage of drivers these days could admit to enacting aggressive and illegal behavior behind the wheel (speeding, running red lights, tailgating), while simultaneously disapproving of those behaviors in others. Given the context of the hunter’s utopia we live in, the answer becomes clear—people will do anything to make their driving more aggressive and effective at enacting violence, but don’t like the idea that others could too, not because there’s a moral problem with that, but because it threatens their dominance in the hunt.

In 2017, I was one of many people nearly killed by James Alex Fields as he rammed his Dodge Challenger into a crowd of protesters in Charlottesville. In addition to giving me terrible PTSD, it also gave me a hatred of Dodge Challengers. It’s no coincidence Fields drove this very American, very muscle-y car. It’s no coincidence that it, along with the Dodge Charger, are the cars most closely associated with the U.S. Military. And it’s no coincidence that fascists, ever the bleeding edge of capitalism, are increasingly using cars as weapons against protestors: cars have become tools of war, and fascists were the first to capitalize on this fact.

But now we’ve all been drafted into the battle, and we’ve all been forced to fight.

My car will be above 100k miles soon, and I’ll likely have to get a new one in the next year or so. Part of me wants another fun, zippy, small car, one that allows me to feel the road, the outside world. But, I don’t know. I might go with something safer and more practical—something that allows me to effectively compete.