Tyranny

Rules

- Don't do unto others what you don't want done unto you.

- No Porn, Gore, or NSFW content. Instant Ban.

- No Spamming, Trolling or Unsolicited Ads. Instant Ban.

- Stay on topic in a community. Please reach out to an admin to create a new community.

As part of the escalating crackdown on free speech in Russia, Twitch streamer Anna Bazhutova, known online as “Yokobovich,” has been condemned to a prison term of five and a half years. Her offense? Criticizing the Russian military’s actions in Ukraine.

Arrested in 2023, Bazhutova, a popular figure on the streaming platform with over 9,000 followers, faced charges for her broadcasts that included witness accounts of atrocities by Russian forces in the Ukrainian city of Bucha.

According to The Moscow Times, the court’s decision came down this month, with Bazhutova found guilty of “spreading false information” about military operations, a charge under Article 207.3 of Russia’s criminal code that can attract a sentence as severe as 15 years. Despite the severe potential maximum, Bazhutova’s sentence was set at just over a third of this possible duration.

Details surrounding the exact timing of the incriminating broadcast are murky, with sources citing either 2022 or 2023 as the year it occurred. Nevertheless, the impact was immediate and severe, drawing ire from authorities and leading to her arrest. Before her trial, Russian police raided her home, seizing electronic devices and detaining Bazhutova, who has been in custody since August 2023.

Her troubles with authorities were compounded in March 2023 when her Twitch channel was abruptly banned, something Twitch is yet to comment on.

Bazhutova’s case is not an isolated incident but part of a broader pattern of punitive measures against those who speak out against the Russian state’s actions in Ukraine.

As the UK prepares for its General Election on July 4th, Meta has announced a series of measures aimed at combating “misinformation” and “hate speech” on its platforms. While the tech giant frames these initiatives as necessary steps to ensure the integrity of the election, critics argue that Meta’s efforts may actually hinder free speech and stifle legitimate political debate.

Meta’s announcement highlights a multi-faceted approach, supposedly drawing on lessons from over 200 elections since 2016 and aligning with the UK’s controversial censorship law, the Online Safety Act.

The company’s track record raises questions about its ability to impartially police content. Critics argue that Meta’s definition of “misinformation” is often too broad and subjective, leading to the removal of legitimate political discourse. By relying on third-party fact-checkers like Full Fact and Reuters, who have their own biases, as everyone does, in the types of content they choose to “fact check,” Meta risks becoming an arbiter of truth, silencing voices that may challenge mainstream narratives.

Meta’s plan to tackle influence operations, including coordinated inauthentic behavior and state-controlled media, sounds, to some, laudable on the surface, the broad and opaque criteria used to determine what constitutes harmful influence could easily be misapplied, leading to the suppression of legitimate outlets that offer alternative perspectives.

The company has faced significant criticism for its handling of misinformation, raising serious concerns about its ability to effectively moderate content. Meta’s handling of the Hunter Biden laptop story in the lead-up to the 2020 US presidential election exacerbated concerns about its content moderation policies. When the New York Post published a story about Hunter Biden’s alleged involvement in questionable overseas business dealings, Meta moved swiftly to limit the spread of the story on its platforms, citing its policy against the dissemination of potentially hacked materials. This decision was widely criticized as a politically motivated act of censorship, particularly after it was revealed that the laptop and its contents were genuine. The suppression of this story fueled accusations of bias and raised questions about the extent to which Meta was willing to go to control the narrative in sensitive political contexts.

Meta’s initiatives are said to protect candidates from “hate speech” and “harassment.” However, the application of these policies often appears inconsistent. Public figures, particularly those with views that are controversial to Big Tech, might find themselves disproportionately targeted by Meta’s enforcement actions.

This selective protection can skew public perception and unfairly disadvantage certain candidates, affecting the democratic process.

Taiwanese who are traveling to China for religious, business or other non-political purposes can all be interrogated by Chinese national security officers due to new national security laws, the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) said in a recent report.

Starting next month, Taiwanese could also be asked to hand over their mobile phones and electronic devices for national security inspections when visiting China, the council said.

Beijing has introduced a series of laws that were designed to impose heavier sanctions on people who are considered enemies of the state.

An amendment to China’s Anti-Espionage Law, which took effect in July last year, expanded the definition of “espionage,” while a new law on guarding state secrets, which was enacted last month, allows the Chinese government to arrest people who are accused of leaking state secrets without following legal procedures.

From next month, municipal-level national security agencies are authorized to issue inspection notices for electronic devices owned by individuals and organizations, while national security officers are allowed to seize electronic devices if the devices contain evidence indicating possible contraventions of national security regulations and that further investigation is required.

Also starting next month, Chinese law enforcement officers who properly identify themselves as police or investigators can search a person’s items if they suspect they are a threat to national security.

They can also secure a search warrant issued by a municipal-level national security agency to search individuals, their personal belongings and facilities with which they are affiliated. People under investigation for national security issues can be asked to sign a non-disclosure agreement if necessary.

Information gathered by the MAC showed that Taiwanese of any profession — college professors, borough wardens, tourists, business personnel or even people traveling for religious purposes — might experience improper treatment and could risk “losing their personal freedom” when visiting China.

In one case, a borough warden who used to be a police officer was asked by Chinese national security personnel to hand over their mobile phone for inspection at the hotel they were staying at, the MAC said, adding that they backed up the phone records as proof.

Another case involved a Taiwanese who had compared the political systems in Taiwan and China online and praised Taiwan for being a democratic and free country.

The person was briefly detained by Chinese customs officers and asked what the purpose of their visit to China was, the MAC said.

Taiwanese doing business in China are not subject to more lenient scrutiny from national security personnel either, the council said.

A Taiwanese employee working for a Taiwanese firm in China was warned not to make any more comments about China’s high youth unemployment rate or economic downturn after being questioned by security personnel for hours, the MAC said.

A Taiwanese working as a chief executive in the Chinese branch of a Taiwanese firm was asked about their political leanings upon arrival, while the chairperson of a private association was interrogated about the association’s operations, the council said.

Meanwhile, an adherent of Yiguandao, which is classified by Beijing as a salvationist religious sect, is still being detained for allegedly breaking the law by bringing books promoting vegetarian food to China, it said.

Some managers of Taiwanese temples reported that they had been asked to provide their personal information and reveal what political parties they supported upon arriving in China, the MAC said.

Some Taiwanese teaching at Chinese universities were asked about their political leanings and who they voted for in the presidential election in January, and Chinese national security officers inspected their laptops and mobile phones.

Some political party members have even been detained until they provide details of how their parties operate, the MAC said.

The European Union is eager to pull Telegram into the realm of its online censorship law, the Digital Services Act (DSA), by declaring that it has enough users to be considered a very large online platform (VLOP) – which DSA can then regulate.

The messaging app’s numbers from February said that it had 41 million monthly active users in the EU’s 27 member countries. But if the EU could find a way to officially push that statistic up to 45 million, then it could subject Telegram to a host of strict DSA rules. And to this end, an “investigation” has reportedly been launched.

The bloc is “in discussion” with those behind the app, unnamed sources have told Bloomberg. What exactly they might be discussing isn’t clear at this time, but Telegram no longer mentions the DSA on its ToS pages, while the one that provided the 41 million figure has been removed from the site.

Telegram has long been a thorn in the side of censorship-prone authorities around the world, and the EU – some of its member countries more so than others – is no different.

Although not as large and influential as Facebook, Google, or even X, unlike these platforms, it remains “unmoderated” and “unaccountable” – i.e., governments who like to suppress online speech on a whim have a hard time trying to achieve this on apps like Telegram.

The EU’s main concern seems to be to fully control the narrative around the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, and be able to block content published by Russian channels as “disinformation” – having long since censored traditional media and platforms based in that country.

The EU appears to be trying to now control Telegram’s reach by “investigating” the number of users it has, and if it finds (or decides) that there are more than 45 million of them in the bloc, the next step would be to try and impose DSA rules on the app.

EU’s punishment for those found in violation of those rules ranges from fines amounting to 6 percent of revenue, to the banning of a platform.

Google has found itself yet another election to “support.”

After the company made announcements to this effect related to the EU (European Parliament) June ballot, voters in the UK can now also look forward to – or dread, as the case may be – the tech giant’s role in their upcoming general election.

A blog post by Google UK Director of Government Affairs and Public Policy Katie O’Donovan announced even more “moderation” and a flurry of other measures, most of which have become tried-and-tested instruments of Google’s censorship over the past years.

They are divided in three categories – pushing (“surfacing”) content and sources of information picked by Google as authoritative and of high quality, along with YouTube information panels, investing in what it calls Trust & Safety operations, as well as “equipping campaigns with the best-in-class security tools and training.”

Another common point is combating “misinformation” – together with what the blog post refers to as “the wider ecosystem.” That concerns Google News Initiative and PA Media, a private news agency, and their Election Check 24, which is supposed to safeguard the UK election from “mis- and dis-information.”

Searches related to voting are “rigged” to return results manipulated to boost what Google considers authoritative sources – notably, the UK government’s site.

As for AI, the promise is that users of Google platforms will receive “help navigating” that type of content.

This includes the obligation for advertisers to reveal that ads “include synthetic content that inauthentically depicts real or realistic-looking people or events” (this definition can easily be stretched to cover parody, memes, and similar).

“Disclosure” here, however, is still differentiated from Google’s outright ban on manipulated media that it decides “misleads people.” Such content is labeled, and banned if considered as having the ability to maybe pose “a serious risk of egregious harm.”

And then there’s Google’s AI chatbot Gemini, which the giant has restricted in terms of what types of election-related queries it will respond to – once again, as a way to root out “misinformation” while promoting “fairness.”

This falls under what the company considers to be “a responsible approach to generative AI products.”

But as always, AI is also seen as a “tool for good” – for example, when it allows for building “faster and more adaptable enforcement systems.”

The EU’s European Commission (EC) appears to be preparing to include “hate speech” among the list of most serious criminal offenses and regulate its investigation and prosecution across the bloc.

Whether this type of proposal is cropping up now because of the upcoming EU elections or if the initiative has legs will become obvious in time, but for now, the plans are supported by several EC commissioners.

The idea stems from the European Citizens’ Panel on Tackling Hatred in Society, one of several panels (ECPs) established to help EC President Ursula von der Leyen with her (campaign?) promise of ushering in a democracy in the EU that is “fit for the future.”

That could mean anything, and the vagueness by no means stops there: the very “hate speech,” despite the gravity of the proposals to classify it as a serious crime, is not even well defined, observers are warning.

Despite that, the recommendations contained in a report produced by the panel have been backed by EC’s Vice-President for Values and Transparency Vera Jourova as well as Vice President for Democracy and Demography Dubravka Suica.

According to Jourova, the panel’s recommendations on how to deal with “hate speech” are “clear and ambitious” – although, as noted, a clear definition of that type of speech is still be lacking.

This is the wording the report went for: any speech that is “incompatible with the values of human dignity, freedom, democracy, the rule of law, and respect of human rights” should be considered as “hate speech.”

Critics of this take issue with going for, in essence, subjective, not to mention vague expressions like “values of human dignity” considering that even in Europe, speech can still be lawful even if individuals or groups perceive it as offensive or upsetting.

Since there is also hate speech that is already illegal in the EU, the panel wants it to receive a new definition, and the goal, the report reads, is to “ensure that all forms of hate speech are uniformly recognized and penalized, reinforcing our commitment to a more inclusive and respectful society.”

If the EU decides to add hate speech to its list of crimes, the panel’s report added, this will allow for the protection of marginalized communities, and “uphold human dignity.”

Noteworthy is that the effort seems coordinated, even as far as the wording goes, as media reports note that the recommendation “adopts exactly the same terminology as an EC proposal that was recently endorsed by the European Parliament to extend the list of EU-wide crimes to include ‘hate speech’.”

In a new lawsuit, Webseed and Brighteon Media have accused multiple US government agencies and prominent tech companies of orchestrating a vast censorship operation aimed at suppressing dissenting viewpoints, particularly concerning COVID-19. The plaintiffs, Webseed and Brighteon Media, manage websites like NaturalNews.com and Brighteon.com, which have been at the center of controversy for their alternative health information and criticism of government policies.

We obtained a copy of the lawsuit for you here.

The defendants include the Department of State, the Global Engagement Center (GEC), the Department of Defense (DOD), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and tech giants such as Meta Platforms (formerly Facebook), Google, and X. Additionally, organizations like NewsGuard Technologies, the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD), and the Global Disinformation Index (GDI) are implicated for their roles in creating and using tools to label and suppress what they consider misinformation.

Allegations of Censorship and Anti-Competitive Practices:

The lawsuit claims that these government entities and tech companies conspired to develop and promote censorship tools to suppress the speech of Webseed and Brighteon Media, among others. “The Government was the primary source of misinformation during the pandemic, and the Government censored dissidents and critics to hide that fact,” states Stanford University Professor J. Bhattacharya in support of the plaintiffs’ claims.

The plaintiffs argue that the government’s efforts were part of a broader strategy to silence voices that did not align with official narratives on COVID-19 and other issues. They assert that these actions were driven by an “anti-competitive animus” aimed at eliminating alternative viewpoints from the digital public square.

According to the complaint, the plaintiffs have suffered substantial economic harm, estimating losses between $25 million and $50 million due to reduced visibility and ad revenue from their platforms. They also claim significant reputational damage as a result of being labeled as purveyors of misinformation.

The complaint details how the GEC and other agencies allegedly funded and promoted tools developed by NewsGuard, ISD, and GDI to blacklist and demonetize websites like NaturalNews.com. These tools, which include blacklists and so-called “nutrition labels,” were then utilized by tech companies to censor content on their platforms. The plaintiffs argue that this collaboration between government agencies and private tech companies constitutes an unconstitutional suppression of free speech.

A Broader Pattern of Censorship:

The lawsuit references other high-profile cases, such as Missouri v. Biden, to illustrate a pattern of government overreach into the digital information space. It highlights how these efforts have extended beyond foreign disinformation to target domestic voices that challenge prevailing government narratives.

Webseed and Brighteon Media are seeking both monetary damages and injunctive relief to prevent further censorship. They contend that the government’s actions violate the First Amendment and call for an end to the use of these censorship tools.

As the case progresses, it promises to shine a light on the complex interplay between government agencies, tech companies, and the tools used to control the flow of information in the digital age. The outcome could have significant implications for the future of free speech and the regulation of online content.

The EU has announced a guiding framework that will make it possible to set up what the bloc calls “Hybrid Rapid Response Teams” which will be “drawing on relevant sectoral national and EU civilian and military expertise.”

These teams will be created and then deployed to counter “disinformation” throughout the 27 member countries – but also to what Brussels calls partner countries. And Ireland might become an “early adopter.”

For a county to apply, it will first need to feel it is under attack by means of “hybrid threats and campaigns” and then request from the EU to help counter those by dispatching a “rapid response team.”

The EU is explaining the need for these teams as a result of a “deteriorating security environment, increasing disinformation, cyber attacks, attacks on critical infrastructure, and election interference by malign actors” – and even something the organization refers to as “instrumentalized migration.”

The framework comes out of the EU Hybrid Toolbox, which itself stems from the bloc’s Strategic Compass for Security and Defense.

Mere days after the EU made the announcement last week, news out of Ireland said that the Department of Foreign Affairs welcomed the development, stating that they will “now begin on operationalizing Ireland’s participation in this important initiative.”

The department explained what it sees as threats – there’s inevitably “disinformation,” along with cyber attacks, attacks on critical infrastructure, as well as “economic coercion.”

Ireland’s authorities appear to be particularly pleased with the EU announcement given that the country doesn’t have a centralized body that would fight such a disparate range of threats, real or construed.

The announcement about the “reaction teams” came from the Council of the EU, and was the next day “welcomed” by the European Commission, which repeated the points the original statement made about a myriad of threats.

The Hybrid Rapid Response Teams which have now been greenlit with the framework are seen as a key instrument in countering those threats.

Other than saying that the EU Hybrid Toolbox relies on “relevant civilian and military expertise,” the two EU press releases are short on detail about the composition of the future teams that will be sent on “short-term” missions.

However, it revealed that “rapid deployment to partner countries” will be made possible through the Emergency Response Coordination Center (ERCC) as the scheme’s operational hub.

The feverish search for the next “disinformation” silver bullet continues as several elections are being held worldwide.

Censorship enthusiasts, who habitually use the terms “dis/misinformation” to go after lawful online speech that happens to not suit their political or ideological agenda, now feel that debunking has failed them.

(That can be yet another euphemism for censorship – when “debunking” political speech means removing information those directly or indirectly in control of platforms don’t like.)

Enter “prebuking” – and regardless of how risky, especially when applied in a democracy, this is, those who support the method are not swayed even by the possibility it may not work.

Prebunking is a distinctly dystopian notion that the audiences and social media users can be “programmed” (proponents use the term, “inoculated”) to reject information as untrustworthy.

To achieve that, speech must be discredited and suppressed as “misinformation” (via warnings from censors) before, not after it is seen by people.

“A radical playbook” is what some legacy media reports call this, at the same time implicitly justifying it as a necessity in a year that has been systematically hyped up as particularly dangerous because of elections taking place around the globe.

The Washington Post disturbingly sums up prebunking as exposing people to “weakened doses of misinformation paired with explanations (…) aimed at helping the public develop ‘mental antibodies’.”

This type of manipulation is supposed to steer the “unwashed masses” toward making the right (aka, desired by the “prebunkers”) conclusions, as they decide who to vote for.

Even as this is seen by opponents as a threat to democracy, it is being adopted widely – “from Arizona to Taiwan (with the EU in between)” – under the pretext of actually protecting democracy.

Where there are governments and censorship these days, there’s inevitably Big Tech, and Google and Meta are mentioned as particularly involved in carrying out prebunking campaigns, notably in the EU.

Apparently Google will not be developing Americans’ “mental antibodies” ahead of the US vote in November – that might prove too controversial, at least at this point in time.

The risk-reward ratio here is also unappealing.

“There aren’t really any actual field experiments showing that it (prebunking) can change people’s behavior in an enduring way,” said Cornell University psychology professor Gordon Pennycook.

Section 230 of the Communications Act (CDA), an online liability shield that prevents online apps, websites, and services from being held civilly liable for content posted by their users if they act in “good faith” to moderate content, provided the foundation for most of today’s popular platforms to grow without being sued out of existence. But as these platforms have grown, Section 230 has become a political football that lawmakers have used in an attempt to influence how platforms editorialize and moderate content, with pro-censorship factions threatening reforms that force platforms to censor more aggressively and pro-free speech factions pushing reforms that reduce the power of Big Tech to censor lawful speech.

And during a Communications and Technology Subcommittee hearing yesterday, lawmakers discussed a radical new Section 230 proposal that would sunset the law and create a new solution that “ensures safety and accountability for past and future harm.”

We obtained a copy of the draft bill to sunset Section 230 for you here.

In a memo for the hearing, lawmakers acknowledged that their true intention is “not to have Section 230 actually sunset” but to “encourage” technology companies to work with Congress on Section 230 reform and noted that they intend to focus on the role Section 230 plays in shaping how Big Tech addresses “harmful content, misinformation, and hate speech” — three broad, subjective categories of legal speech that are often used to justify censorship of disfavored opinions.

And during the hearing, several lawmakers signaled that they want to use this latest piece of Section 230 legislation to force social media platforms to censor a wider range of content, including content that they deem to be harmful or misinformation.

Rep. Doris Matsui (D-CA) acknowledged that Section 230 “allowed the internet to flourish in its early days” but complained that it serves as “a haven for harmful content, disinformation, and online harassment.”

She added: “The role of Section 230 needs immediate scrutiny, because as it exists today, it is just not working.”

Rep. John Joyce (R-PA) suggested Section 230 reforms are necessary to protect children — a talking point that’s often used to erode free speech and privacy for everyone.

“We need to make sure that they [children] are not interacting with harmful or inappropriate content,” Rep. John Joyce (R-PA) said. “And Section 230 is only exacerbating this problem. We here in Congress need to find a solution to this problem that Section 230 poses.”

Rep. Tony Cárdenas (D-CA) complained that platforms aren’t doing enough to combat “outrageous and harmful content” and “harmful mis-and-dis-information”:

“While I wish we could better depend on American companies to help combat these issues, the reality is that outrageous and harmful content helps drive their profit margins. That’s the online platforms. I’ll also highlight, as I have in previous hearings, that the problem of harmful mis-and-dis-information online is even worse for users who speak Spanish and other languages outside of English as a result of platforms not making adequate investments to protect them.”

Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-MI) also signaled an intent to use Section 230 reform to target “false information” and claimed that Section 230 has allowed platforms to “evade accountability for what occurs on their platforms.”

Rep. Buddy Cater (R-GA) framed Section 230 as “part of the problem” because “it’s kind of set a free for all on the Internet” when pushing for reform.

While several lawmakers were in favor of Section 230 reforms that pressure platforms to moderate more aggressively, one of the witnesses, Kate Tummarello, the Executive Director at the advocacy organization Engine, did warn that these efforts could lead to censorship.

“It’s not that the platforms would be held liable for the speech,” Tummarello said. “It’s that the platforms could very easily be pressured into removing speech people don’t like.”

You can watch the full hearing here.

Some members of Congress want to delete Section 230, the key law underpinning free speech online. Even though this law has protected millions of Americans’ right to speak out and organize for decades, the House is now debating a proposal to “sunset” the law after 18 months.

Section 230 reflects values that most Americans agree with: you’re responsible for your own speech online, but, with narrow exceptions, not the speech of other people. This law protects every internet user and website host, from large platforms down to the smallest blogs. If Congress eliminates Section 230, we’ll all be less free to create art and speak out online.

Section 230 says that online services and individual users can’t be sued over the speech of other users, whether that speech is in a comment section, social media post, or a forwarded email. Without Section 230, it's likely that small platforms and Big Tech will both be much more likely to remove our speech, out of fear it offends someone enough to file a lawsuit.

Section 230 also protects content moderators who take actions against their site’s worst or most abusive users. Sunsetting Section 230 will let powerful people or companies constantly second-guess those decisions with lawsuits—it will be a field day for the worst-behaved people online.

The sponsors of this bill, Reps. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) Frank Pallone (D-NJ), claim that if it passes, it will get Big Tech to come to the table to negotiate a new set of rules around online speech. Here’s what supporters of this bill don’t get: everyday users don’t want Big Tech to be in Washington, working with politicians to rewrite internet speech law. That will be a disaster for us all.

We need your help to tell all U.S. Senators and Representatives to oppose this bill, and vote no on it if it comes to the floor.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is campaigning to get reelected (by the next European Parliament, EP) and her messaging ahead of EP elections next month unsurprisingly includes doubling down on the policy of “combating disinformation.”

But in the same breath, the EU bureaucrat was not shy to make unsubstantiated accusations against some European politicians – specifically the opposition in her native Germany, that’s rapidly gaining in popularity – describing them as being “in the pockets of Russia.”

She also pledged that the European Commission under her continued leadership will make “European Democracy Shield” a priority.

This is supposed to be a new body coordinating EU member-countries’ national agencies as they search for “information and manipulation.”

“Better information and threat intelligence sharing” is given as the entity’s key role, while it will be modeled after Sweden’s Psychological Defense Agency.

Von der Leyen proceeded to show a poor understanding of the concepts of misinformation, cyber attacks, and extremism, conflating them while warning of foreign influence and manipulation.

“It is about confusing people so they don’t know who to believe or if they can even believe anyone at all” – she said, although her own statements can be read as achieving just that effect.

The European Commission president went on to praise the Digital Services Act, a controversial censorship law, and spoke about the need for the bloc to be “very vigilant and uncompromising when it comes to ensuring that it is properly enforced.”

“We have already made progress with the DSA…so once we have detected malign information or propaganda, we need to ensure that it is swiftly removed and blocked,” von der Leyen said.

Von der Leyen covered most of the censorship bases in her speech, including by pushing for the dystopian mechanism of “prebunking” – where citizens are in advance “warned” (“inoculated”) by the censors about supposed misinformation, in order to influence how they perceive information.

“Pre-bunking is much more successful than debunking,” she said. “Pre-bunking is basically the opposite of debunking… It is much better to vaccinate so that the body is inoculated.”

The latest of Canada’s speech-restricting legislative efforts, the Online Harms Act (Bill C-63) was introduced and promoted earlier in the year by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau as necessary primarily to protect children and vulnerable population categories on the internet.

The actual text of the bill, however, reveals broad implications, including sweeping censorship and draconian penalties, as yet another country pushes such measures under the “think of the children” banner.

We obtained a copy of the bill for you here.

And here, the message was “garnished” with Trudeau’s early assurances that the bill would be focused on the stated goals.

But upon closer inspection, several controversial provisions have emerged, making Bill C-63 opponents liken it to all manner of dystopian concepts, from “1984” to “Minority Report.”

One of them, addressing “Continuous Communication” (Section 13-2) could see Canada’s Charter of Freedoms violated by retroactively censoring speech, i.e., punishing “perpetrators” for content posted before the new law, that defines it an offense, gets enacted.

The bill states that, “a person communicates or causes to be communicated hate speech so long as the hate speech remains public and the person can remove or block access to it.”

Critics believe that this paves the way for the clause to be used retroactively against those who fail to remove their past statements from the internet.

This could become both a tool of censorship and an intimidation tactic aimed at suppressing future speech, by demonstrating what happens to those found in violation of the law.

And what can happen to them is by no means trivial: life imprisonment is envisaged as a possible punishment for “any offense motivated by hatred.”

This is an example of the bill’s astonishingly overbroad nature, where interpretations of what “hatred motivated offense” is can range from advocating genocide, to a misdemeanor that is found to have been committed “with hateful intent.”

More dystopian concepts are woven into the text, such as “pre-crime” – and this could land people in jail for up to a year or put them under house arrest. That’s jail time for a “hate crime” that was never committed.

Meanwhile, online platforms are required to swiftly, in some cases in under 24 hours, remove content Canadian authorities label as harmful, or risk fines of up to 6 percent of their gross global revenue.

YouTube has (“voluntarily” or otherwise) assumed the role of a private business entity that “supports elections.”

Google’s video platform detailed in a blog post how this is supposed to play out, in this instance, in the EU.

With the European Parliament (EP) election just around the corner, YouTube set out to present “an overview of our efforts to help people across Europe and beyond find helpful and authoritative election news and information.”

The overview is the usual hodgepodge of reasonable concepts, such as promoting information on how to vote or register for voting, learning about election results, etc., that quickly morph into yet another battle in the “war on disinformation.”

And what better way to “support” an election (and by extension, democracy) – than to engage in another round of mass censorship? /s

But YouTube was happy to share that in 2023 alone, it removed 35,000 videos uploaded in the EU, having decided that this content violated the platform’s policies, including around what the blog post calls “certain types of elections misinformation” (raising the logical question if some types of “election misinformation” might be allowed).

As for who is doing this work, YouTube suggests it is a well-oiled machine hard at it around the clock, and “at scale” – made up of “global teams of reviewers” and machine learning algorithms.

The blog post first states that one of the goals of YouTube’s efforts is to help users “learn about the issues shaping the debate.” But then in the part of the article that goes into how the platform is “dealing with harmful content,” it at one point starts to look like the giant might be trying to shape that debate itself.

“Our Intelligence Desk has also been working for months to get ahead of emerging issues and trends that could affect the EU elections, both on and off YouTube,” reads the post.

In case somebody missed the point, YouTube reiterates it: “This helps our enforcement teams to address these potential trends before they become larger issues.”

And while machine learning (aka, AI) is mentioned as a positive when it comes to powering YouTube’s ability to censor at scale, later on in the post the obligatory mention is made of AI as a tool potentially dangerous to elections and democracy.

YouTube also states that coordinated influence campaigns are banned on the platform – and promises that this is true “regardless of the political viewpoints they support.”

And when Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG) decides it has spotted such a campaign, this information is shared with law enforcement, including EUROPOL.

The Russian government has officially blocked access to the video-sharing platform Rumble, following the company’s refusal to comply with demands for censorship. That’s according to Chris Pavlovski, CEO of Rumble, who confirmed the news, highlighting the platform’s commitment to free speech and its refusal to bend to external pressures.

“Russia has officially blocked Rumble because we refused to comply with their censorship demands,” Pavlovski stated. He pointed out the apparent contradiction in the treatment of different tech companies, noting, “Ironically, YouTube is still operating in Russia, and everyone needs to ask what Russian demands Google and YouTube are complying with?”

The block comes amid heightened tensions over internet freedoms in Russia. The government has been tightening its grip on online content, demanding that platforms remove or block content it deems politically sensitive or harmful.

This action against Rumble raises questions about the operations of other tech giants in the country, notably YouTube. The Google-owned video service continues to operate, suggesting it may be meeting Russian regulatory demands that Rumble has rejected.

In a revealing X Spaces interview, Pavlovski elaborated on the recent decision by Russia to block the platform, a move he connects to the company’s firm stance against censorship demands. Pavlovski drew parallels between current events and past challenges, notably referencing a similar situation in France.

“Two years ago we left France; they threatened to turn us off at the telco level so we decided to make the decision to leave the country entirely,” Pavlovski said. France was demanding that Rumble shut down Russian news sources. Pavlovski highlighted the significant media attention this decision received previously, which contrasts sharply with the current underreporting of Rumble’s ban in Russia. “And every single paper in the United States and in Canada covered how we were allowing Russian news sources on Rumble,” he added.

Pavlovski detailed that Rumble had received multiple requests from the Russian government to censor various channels, which did not violate their terms of service. He listed the types of content involved: “One of the accounts was with respect to marijuana, another seemed to be like some kind of conspiracy channel… And the other channel seemed to be an Arabic channel that was political…”

By refusing these demands, Rumble was subsequently made inaccessible within Russia. Pavlovski emphasized the implications for other platforms still operating in Russia, raising questions about their compliance. “Rumble has been the tip of the spear when it comes to free expression… So what does that mean? Are [other platforms] complying with every single request that comes? Or what is exactly happening? I think that’s a really important question that everyone needs to ask because obviously Rumble is not as big as YouTube.”

Pavlovski mentioned that they suspected for about a month that Russia was blocking Rumble, but it was only confirmed this week: “It might have happened about a month ago, but we confirmed that Russia has put Rumble on a block list and we’re completely inaccessible within Russia. Entirely.”

The news of the Russia block followed Pavlovski’s testimony in dealing with another country’s censorship demands – Brazil. On Tuesday, Pavlovski spoke before the House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee, detailing the company’s withdrawal from Brazil due to censorship demands by the nation’s left-wing judiciary.

The hearing, chaired by Rep. Chris Smith, explored the erosion of civil liberties in Brazil under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes. Witnesses, including American journalist Michael Shellenberger, criticized the Brazilian government’s repressive tactics, which have stifled free expression and led to accusations of criminal activity against those exposing government censorship.

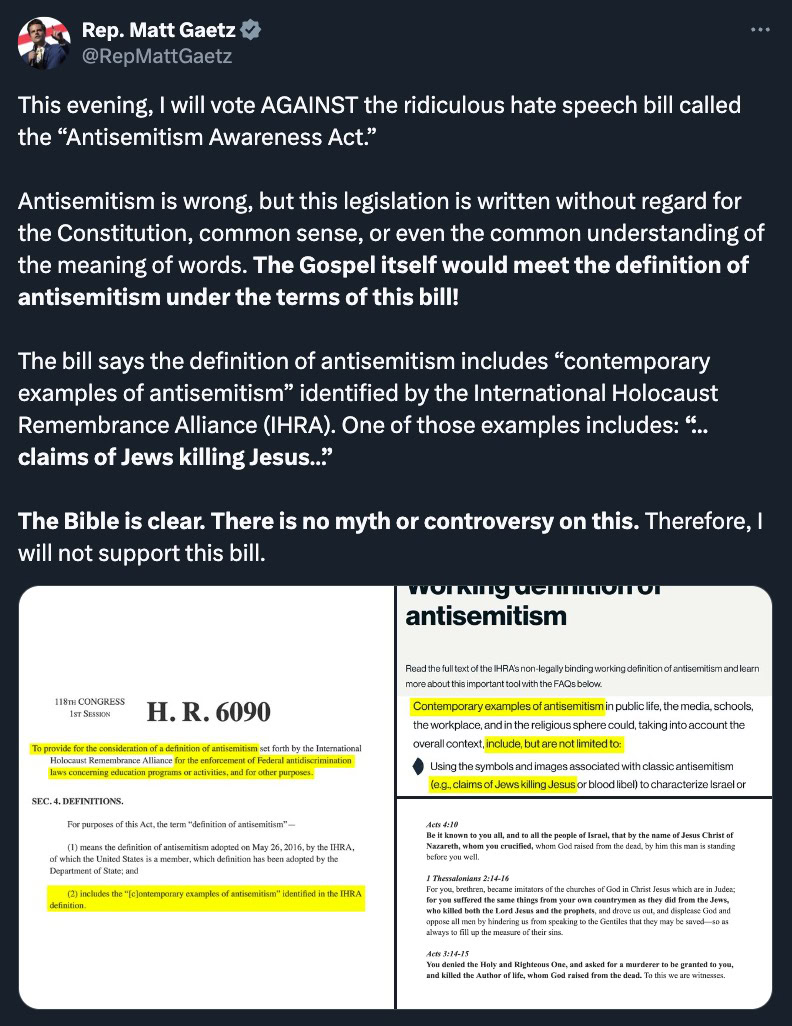

In response to the ongoing tensions concerning Israel and Hamas, coupled with a wave of pro-Palestinian protests at colleges across the United States, the US House of Representatives, led by a New York Republican, voted in favor of a divisive antisemitism awareness bill. Despite engendering controversy, the bill was successful with 320 votes for and 91 against, manifesting some level of bipartisan support.

The legislation, fronted by Mike Lawler, aims to “provide for the consideration of a definition of antisemitism set forth by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance for the enforcement of federal anti-discrimination laws concerning education programs or activities, and for other purposes.”

The legislation mandates that the Department of Education adopt the IHRA’s definition of antisemitism to enforce anti-discrimination laws.

The bill faced opposition beyond political disagreements. The American Civil Liberties Union also disapproved of the legislation, pointing out that antisemitic discrimination and harassment by federally funded bodies were already legally prohibited. The Union contended that the bill’s presence is unnecessary for combating antisemitism and instead, it may curb free speech among college students by misinterpreting criticism of the Israeli government as antisemitism.

Critics of the bill, however, including Rep. Matt Gaetz, argue it infringes on free speech. Gaetz notably derided the measure as a “ridiculous hate speech bill” and voiced his concerns that it could potentially label biblical passages as antisemitic.

Expressing his stance on the social platform X, Gaetz announced, “This evening, I will vote AGAINST the ridiculous hate speech bill called the ‘Antisemitism Awareness Act.’”

He elaborated, stating, “Antisemitism is wrong, but this legislation is written without regard for the Constitution, common sense, or even the common understanding of the meaning of words. The Gospel itself would meet the definition of antisemitism under the terms of this bill!” According to Gaetz, the bill’s definition of antisemitism, as per the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), would include biblical assertions such as “claims of Jews killing Jesus.”

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene also opposed the bill for similar reasons. She argued that it could unjustly accuse Christians of antisemitism simply for adhering to Gospel narratives. “The bill could convict Christians of antisemitism for believing the Gospel that says Jesus was handed over to Herod to be crucified by the Jews,” she stated on social media.

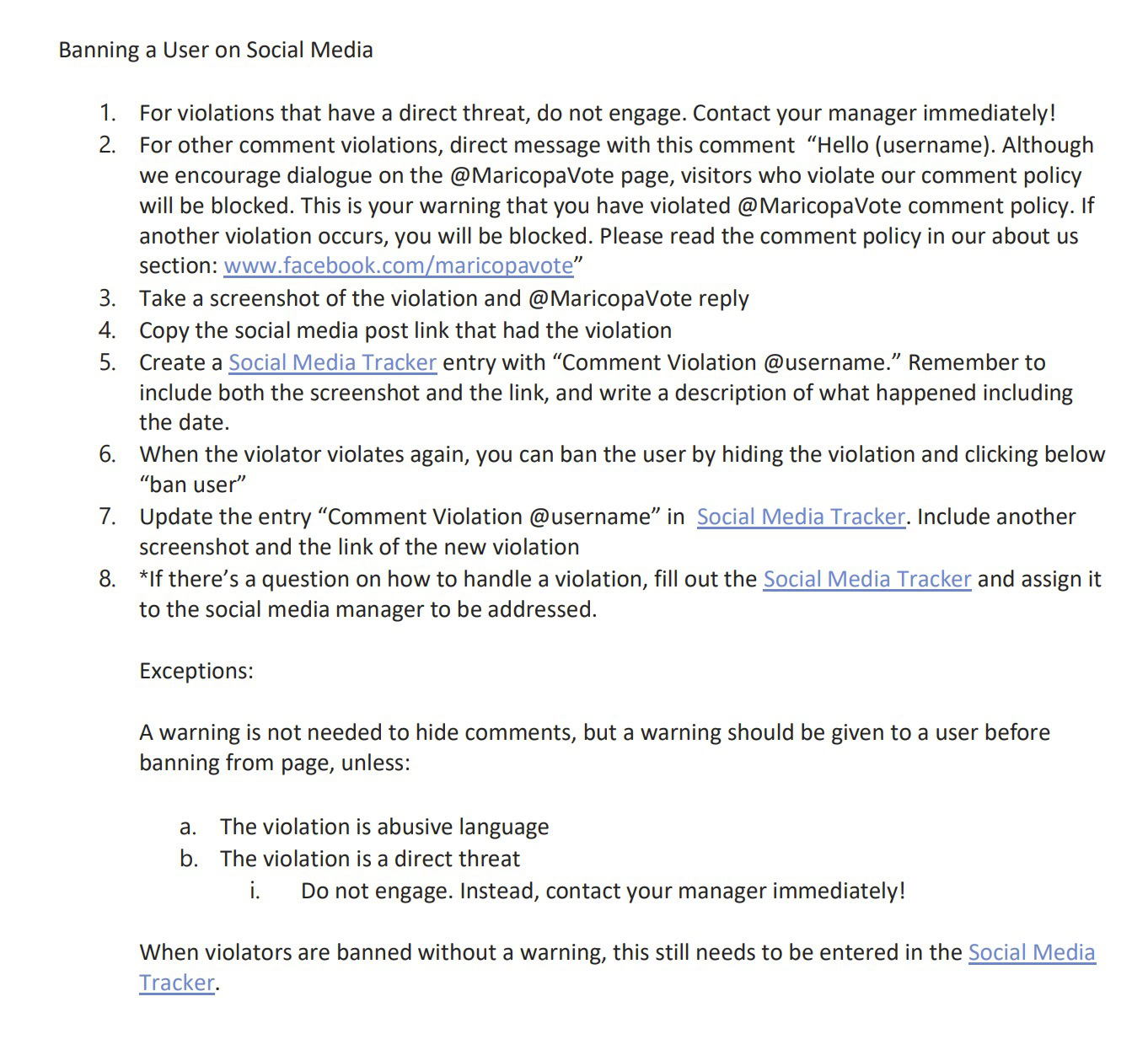

The Arizona Secretary of State’s Office and the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office have been exposed as doing their best to team up with social media companies, non-profits, as well as the US government to advance online censorship.

This, yet another case of “cooperation” (aka, collusion) between government and private entities to stifle speech disapproved of by federal and some state authorities has emerged from several public records, brought to the public’s attention by the Gavel Project.

The official purpose of several initiatives was to counter “misinformation” using monitoring and reporting whatever the two offices decided qualified; another was to censor content on social platforms, while plans also included restricting discourse to the point of banning users from county-run accounts.

“Online harassment” was another target, and Maricopa County took it upon itself to “identify” – and then report to law enforcement.

One striking example of the mindset behind all this is a draft of a speech County Recorder Stephen Richer delivered to Maricopa Community Colleges.

As reports note, Richer is hoping to be reelected this year, while back in September 2021, he complained that “lies and disinformation” are undermining “the entire election system.”

“And it is in this respect, that the Constitution today is in some ways a thorn in the side of my office. Specifically the First Amendment,” Richer said – before declaring himself “a huge fan of the Constitution.”

When his office was earlier in the month asked to, essentially, “make it make sense” – they didn’t, stating only that Richer “stands by his speech (…) especially the part where he says he’s ‘a huge fan of the Constitution’.”

And while there was no denying the fact that the official expressed these sentiments, more revelations from the documents – including the banning of users from official social media accounts – are now described by Maricopa County as drafts that were “never implemented.”

Even those willing to take the county’s word at face value might be surprised to learn what some of those “never implemented” plans included.

One was, opponents might say, to spread their own propaganda. Like so: “(Partnering) with influencers in our community and across the country who share our desire to spread accurate information about elections and combat disinformation.”

This document, titled, “Building a Partnership of Election Fact Ambassadors,” is believed to have been drafted around the 2022 midterm elections.

Earlier, now former Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, “worked with social media companies and censorship nonprofits to track election information online and combat it when they deemed necessary,” say reports citing the public records.

“We’ve heard feedback from elections authorities that they need better tools to track potential voter interference content on Facebook,” Facebook told her office in a September 2019 email, adding:

“In response to this feedback, we are building a dashboard that will track this content in each state – and we’d like to share those dashboards with the respective elections authorities. These Dashboards will allow for keyword searches of public content on Facebook in each state – and will be able to be customized to each state’s needs.”

Hobbs welcomed this development as “great news.”

If you have been using the internet for longer than a couple of years, you might have noticed that it used to be much “freer.” What freer means in this context is that there was less censorship and less stringent rules regarding copyright violations on social media websites such as YouTube and Facebook (and consequently a wider array of content), search engines used to often show results from smaller websites, there were less “fact-checkers,” and there were (for better or for worse) less stringent guidelines for acceptable conduct.

In the last ten years, the internet structure and environment have undergone radical changes. This has happened in many areas of the internet; however, this article will specifically focus on the changes in social media websites and search engines. This article will argue that changes in European Union regulations regarding online platforms played an important role in shaping the structure of the internet to the way it is today and that further changes in EU policy that will be even more detrimental to freedom on the internet may be on the horizon.

Now that readers have an idea of what “change” is referring to, we should explain in detail which EU regulations played a part in bringing it about. The first important piece of regulation we will deal with is the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market that came out in 2019. Article 17 of this directive states that online content-sharing service platforms are liable for the copyrighted content that is posted on their websites if they do not have a license for said content. To be exempt from liability, the websites must show that they exerted their best efforts to ensure that copyrighted content does not get posted on their sites, cooperated expeditiously to take the content down if posted, and took measures to make sure the content does not get uploaded again. If these websites were ever in a place to be liable for even a significant minority of the content uploaded to them, the financial ramifications would be immense. Due to this regulation, around the same period, YouTube and many other sites strengthened their policy regarding copyrighted content, and ever since then—sometimes rightfully, sometimes wrongfully—content creators have been complaining about their videos getting flagged for copyright violations.

Another EU regulation that is of note for our topic is the Digital Services Act that came out in 2023. The Digital Services Act is a regulation that defines very large online platforms and search engines as platform sites with more than forty-five million active monthly users and places specific burdens on these sites along with the regulatory burden that is eligible for all online platforms. The entirety of this act is too long to be discussed in this article; however, some of the most noteworthy points are as follows:

- The EU Commission (the executive body of the EU) will work directly with very large online platforms to ensure that their terms of service are compatible with requirements regarding hate speech and disinformation as well as the additional requirements of the Digital Services Act. The EU Commission also has the power to directly influence the terms of conduct of these websites.

- Very large online platforms and search engines have the obligation to ban and preemptively fight against and alter their recommendation systems to discriminate against many different types of content ranging from hate speech and discrimination to anything that might be deemed misinformation and disinformation.

These points should be concerning to anyone who uses the internet. The vagueness of terms such as “hate speech” and “disinformation” allows the EU to influence the recommendation algorithms and terms of service of these websites and to keep any content that goes against their “ideals” away from the spotlight or away from these websites entirely. Even if the issues that are discussed here were entirely theoretical, it would still be prudent to be concerned about a centralized supragovernmental institution such as the EU having this much power regarding the internet and the websites we use every day. However, as with the banning of Russia Today from YouTube, which was due to allegations of disinformation and happened around the same time the EU placed sanctions on Russia Today, we can see that political considerations can and do lead to content being banned on these sites. We currently live in a world with an almost-infinite amount of information; due to this, it would be impossible for anyone or even any institution to sift through all the data surrounding any issue and to come up with a definitive “truth” on the subject, and this is assuming that said persons or institution is unbiased on the issue and approaching it in good faith, which is rarely the case. All of us have ways of viewing the world that filter our understanding of issues even when we have the best intentions, not to mention the fact that supranational bodies such as the EU and the EU Commission have vested political incentives and are influenced by many lobbies, which may render their decisions regarding what is the “truth” and what is “disinformation” to be faulty at best and deliberately harmful at worst. All of this is to say that in general, none of us—not even the so-called experts—can claim to know everything regarding an issue enough to make a definitive statement as to what is true and what is disinformation, and this makes giving a centralized institution the power to constitute what the truth is a very dangerous thing.

The proponents of these EU regulations argue that bad-faith actors may use disinformation to deceive the public. There is obviously some truth in this; however, one could also argue that many different actors creating and arguing their own narrative with regard to what is happening around the world are preferable to a centralized institution controlling a unified narrative of what is to be considered the “truth.” In my scenario, even if some people are “fooled” (even though to accurately consider people to be fooled, we would have to claim that we know the definitive truth regarding a multifaceted complex issue that can be viewed from many angles), the public will get to hear many narratives about what happened and can make up their own minds. If this leads to people being fooled by bad-faith actors, it will never be the entirety of the population. Some people will be “fooled” by narrative A, some by narrative B, some by narrative C, and so forth. However, in the current case, if the EU is or ever becomes the bad-faith actor who uses its power to champion its own narrative for political purposes, it has the power to control and influence what the entirety of the public hears and believes with regard to an issue, and that is a much more dangerous scenario than the one that would occur if we simply let the so-called wars of information be waged. The concentration of power is something that we should always be concerned about, especially when it comes to power regarding information since information shapes what people believe, and what people believe changes everything.

Another important thing to note is that just because it is the EU that makes these regulations does not change the fact that it affects everyone in the world. After all, even if someone posts a video on YouTube from the United States or from Turkey, it will still face the same terms of service. Almost everyone in the world uses Google or Bing, and the EU has power over the recommendation algorithms of these search engines. This means that the EU has the power over what information most people see when they want to learn something from the internet. No centralized institution can be trusted with this much power.

One final issue of importance is the fact that the EU is investing in new technologies such as artificial intelligence programs to “tackle disinformation” and to check the veracity of content posted online. An important example of this is the InVID project, which is in its own words “a knowledge verification platform to detect emerging stories and assess the reliability of newsworthy video files and content spread via social media.” If you are at all worried about the state of the internet as explained in this article, know that this potential development may lead to the EU doing all of the things described here in an even more “effective” manner in the future.

Authored by Turner Wright via CoinTelegraph.com,

Officials with the United States Department of Justice announced charges against early Bitcoin investor Roger Ver, known by many as ‘Bitcoin Jesus.’

In an April 30 notice, the Justice Department said authorities in Spain had arrested Ver based on criminal charges in the United States, including mail fraud, tax evasion and filing false tax returns.

The U.S. government alleged Ver defrauded the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) out of roughly $48 million with his failure to report capital gains on his sale of Bitcoin and other assets.

According to the indictment filed on Feb. 15 but unsealed on April 29, Ver allegedly took control of roughly 70,000 BTC in June 2017 - before the now famous bull run - and sold many of them for $240 million. U.S. officials said they planned to extradite Ver from Spain to the United States to stand trial.

Reactions to Ver’s arrest on social media were mixed.

However, Bitcoiner Dan Held, the former growth lead at Kraken, claimed Ver “deserves everything that he’s about to get” after he “nearly destroyed Bitcoin.”

“Roger attacked my livelihood by trying to get me fired, called up others to hurt my relationships, and attacked my reputation,” said Held on X.

“He misaligned expectations around Bitcoin so much that it led to a civil war.”

A cryptic message was Ver's most-recent post on X, reading:

Ver was also a proponent of Bitcoin Cash.

In 2022, he became embroiled in a scandal with crypto investment platform CoinFlex, which claimed he owed them $47 million in USD Coin.

He had not commented on social media regarding the Justice Department charges at the time of publication.

A former Riverside County Sheriff’s deputy, who was apprehended last year as part of an investigation into the Sinaloa cartel, has been found to have been working for "El Chapo" himself.

25 year old Jorge Oceguera-Rocha resigned from his position with the Sheriff after being caught with over 100 pounds of fentanyl pills and a firearm during a traffic stop in Calimesa, in September of last year, KTLA reports.

Authorities did not specify how they discovered his alleged involvement in drug trafficking, but he was identified as a “corrupt Riverside County Correctional Deputy” mentioned in a press release about Operation Hotline Bling.

In March 2023, the Drug Enforcement Administration Riverside District Office and the Riverside Police Department, with assistance from the United States Postal Inspection Service, initiated Operation “Hotline Bling.” During the investigation, agents seized a total of approximately 376 pounds of methamphetamine, 37.4 pounds of fentanyl, 600,000 fentanyl tablets, 1.4 kilograms of cocaine, and seven firearms. The drugs seized in this investigation have an estimated “street value” of $16 million.

This operation targeted Sinaloa cartel activities in the Inland Empire, resulting in 15 arrests and the seizure of $16 million worth of narcotics. The Sinaloa cartel, once led by Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, is renowned for its influence akin to that of Pablo Escobar in the 1980s and early ’90s.

Oceguera-Rocha faces multiple local felony charges and the Sheriff’s Department confirmed his involvement in trafficking narcotics within Riverside County while off duty.

Although federal prosecutors didn't press charges, Riverside County officials charged him with possession and transportation of narcotics, with enhancements for the drug's weight, and possession of a firearm in connection with narcotics.

The initial report on the arrest noted he was being detained at the John Benoit Detention Center with a $5 million bail, justified by the drug's weight and potential flight risk. If convicted, he faces up to 10 years in jail.

The United Nations continues with an attempt to advance the agenda to get what the organization calls its Code of Conduct for Information Integrity on Digital Platforms implemented.

This code is based on a previous policy brief that recommends censorship of whatever is deemed to be “disinformation, misinformation, hate” but that is only the big picture of the policy UN Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications Melissa Fleming is staunchly promoting.

In early April, Fleming gave a talk at Boston University, and here the focus was on AI, whose usefulness in various censorship ventures makes it seen as a tool that advances “resilience in global communication.”

A piece on the Boston University Center on Emerging Infectious Diseases site first asserts that AI had a “major role” in helping spread misinformation and conspiracy theories “in the post-pandemic era,” while the UN is described as one of the institutions that have been undermined by all this, while “working to dispel these narratives.”

(The article also – helpfully, in terms of understanding where its authors are coming from – cites the World Economic Forum (WEF) as the “authority” which has proclaimed that “the threat from misinformation and disinformation as the most severe short-term threat facing the world today”).

You will hardly hear Fleming disagreeing with any of this, but the UN’s approach is to “harness” that power to serve its own agendas. The UN official’s talk was about AI can be used to feed the public the desired narratives around issues like vaccines, climate change, and the “well-being” of women and girls.

However, she also went long into all the aspects of AI that she perceives as negative, throwing pretty much every talking point already well established among the “AI fear-mongering genre” in there:

“One of our biggest worries is the ease with which new technologies can help spread misinformation easier and cheaper, and that this content can be produced at scale and far more easily personalized and targeted,” she said.

Flemming said that with the pandemic, this “skyrocketed” around the issue of vaccines. But she didn’t address why that may be – other than, apparently, being simply a furious sudden proliferation of “misinformation” for its own sake.

Flemming then mentions a number of UN activities, basically along the lines of “fact-checking” and “pre-bunking” (like “Verified,” and #TakeCareBeforeYouShare”).

Some might refer to Flemming as one of the “merchants of outrage” but she has this slur reserved for others, such as “climate (change) deniers.”

And it wasn’t long before X and Elon Musk cropped up.

“Since Elon Musk took over X, all of the climate deniers are back, and (the platform) has become a space for all kinds of climate disinformation. Here is a connection that people in the anti-vaccine sphere are now shifting to the climate change denial sphere,” Flemming lamented.

But, the UN official reassured everyone that “she and her team are working to build coalitions and initiatives that leverage AI to promote exciting, positive, fact-driven global public health communications.”

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg has widened his campaign against untraceable “ghost guns,” by pushing for YouTube to remove videos about such topics.

According to Bragg, YouTube’s recommendation algorithm paves a path from shooter-style video game guides to homemade firearm assembly via 3D printing instructions.

We obtained a copy of Bragg’s letter to YouTube here.

“We are seeing actual cases with actual people with ghost guns who are telling us they got the ghost gun because of YouTube,” Bragg alleged, causing him to set his sights on the video giant.

The DA’s office used YouTube screenshots to illustrate how suggestions from popular Call of Duty (a game with an age rating of 18+) gameplay subsequently led to tutorial videos on 3D-printed firearms construction.

Bragg used the idea that the videos could be recommended to kids to further pressure the platform to remove the videos.

“All you need is a computer and a mouse and an interest in gaming, and you can go from games to guns in 15 minutes,” Bragg said.

“What we want to happen today is for YouTube to not have an algorithm that pushes people, especially our youth, to ghost guns,” he complained.

New York has implemented stringent measures to combat the proliferation of ghost guns, untraceable firearms often assembled from kits or 3D-printed components.

In 2021, the state passed legislation that explicitly banned the sale, possession, and distribution of ghost gun parts and kits, suggesting a growing threat these unregistered firearms pose to public safety.

The new laws make it illegal to own or sell any gun that lacks a serial number, a crucial step to prevent untraceable weapons from circulating in the black market.

But content about ghost guns, including discussions on how to assemble them or create 3D-printed firearm components is, many free speech groups agree, likely protected by the First Amendment of the US Constitution, which guarantees freedom of speech and expression.

Many rights groups, such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), contend that even blueprints for creating firearms, including those for ghost guns, are protected by the First Amendment.

This stance is rooted in the belief that information, in its various forms, is a form of speech. This extends to digital files, like blueprints and code, used to create 3D-printed guns or assemble other untraceable firearms.

Politicians are increasingly becoming comfortable in pressuring tech platforms to remove certain types of content, citing public safety and national security concerns.

The draconian sentence of a celebrated Iranian rapper, known for his staunch opposition to the regime, offers a stark portrait of Iran’s stifling repression of freedom of speech. Toomaj Salehi, 33, is set to face the gallows after he supported and posted pictures of himself amidst the crowds advocating for the cause of Mahsa Amini, an Iranian Kurd who was killed in police custody after being detained for improper wearing of a hijab.

The news about the execution order was shared on Wednesday by Mr. Salehi’s legal counsel with the Iranian newspaper, Sharq.

Salehi had previously raised his voice in support of a string of demonstrations, which rallied under the banner “Women, Life, Freedom.” His online posts led to his detention in October of 2022.

The rapper, additionally, courted controversy by leveraging his art to share online messages critical of the Iranian regime. His songs, openly advocating for more liberties and women’s rights, struck a chord with many.

Amini’s life was cut short in September of 2022 after being apprehended on allegations of violating the country’s stringent hijab rules. Her death set off a sweeping tide of public unrest that not only resulted in thousands of arrests but also led to claims of torture and even fatalities at the hands of Iranian law enforcement. Iran notoriously shut off internet access in an attempt to curb the protests.

In light of his musical activism and public statements supporting the demonstrations, Salehi had his first brush with the law in 2022. Paradoxically, he managed to evade capital punishment last year following his arrest ordeal. Instead, he was given a prison sentence of six years and three months for “corrupting planet Earth.”

He escaped the fatal verdict due to a Supreme Court intervention that deemed flaws with his initial sentence leading to its relegation to a lower court for reassessment.

“Branch One of the Revolutionary Court of Isfahan in an unprecedented move, did not enforce the Supreme Court’s ruling…and sentenced Salehi to the harshest punishment,” his lawyer Amir Raisian told Sharq.

As of May 17, TikTok will start implementing new rules affecting content appearing on the app’s For You feed (FYF), and the changes are prompted by concerns about so-called “harmful speech” and “misinformation.”

FYF is vital for the visibility of content, since it opens and plays videos automatically when the app is launched, something TikTok refers to as its “personalized recommendation system.”

A post on the company’s site titled, “For You feed Eligibility Standards,” reveals that content that is deemed as health or news “misinformation” will be censored from this tab more stringently going forward.

On the health side, TikTok looks to clamp down on anything from videos promoting “unproven treatments,” dieting and weight loss, plastic surgery (unless related risks are included as well), videos allegedly misrepresenting scientific findings, to the very broadly defined content that is considered misleading, and “could potentially” cause harm to public health.

Clarity is not the announcement’s strong suit, and so the new rules will tackle even such things as “overgeneralized mental health information.” Also in the FYF “doghouse” will be content that’s found to be too focused on “sadness” (including “sharing sad quotes”).

Then there’s the blog post’s “explanation” that some types of content “may be fine if seen occasionally, but problematic if viewed in clusters.”

What this actually means is control of users’ exposure to content at its finest: “We will interrupt repetitive content patterns to ensure it is not viewed too often,” TikTok said.

When it comes to hate speech, “outlawed” is now even “some content” that is deemed to be making insinuations or indirect statements about protected groups – such that “may implicitly demean” them.

Dangerous activities and challenges are also banned from FYF – apparently only if they lead to “moderate physical harm.” And if you’d like your videos of people “wearing only nipple covers or underwear that does not cover the majority of the buttocks” to be featured, well, you’re also out of luck.

Other than disappearing from FYF, users who repeatedly post speech offending to TikTok’s new rules content will get deranked in the app’s search.

There’s sexually suggestive and graphic content (including fictional graphic violence), also defined in some interesting, at times overly vague, at others oddly specific ways.

And, naturally, the new rules deal with “misinformation” and “election integrity.”

In the first category, “not eligible for FYF” are “conspiracy theories that are unfounded and claim that certain events or situations are carried out by covert or powerful groups, such as ‘the government’ or a ‘secret society’.”

The second seeks to remove “unverified claims about an election, such as a premature claim that all ballots have been counted or tallied; statements that significantly misrepresent authoritative civic information, such as a false claim about the text of a parliamentary bill.”