In the first six months of the second Trump administration, some 60,000 federal workers have been targeted for layoffs, even more have taken buyouts, and up to trillions of dollars in funding has been frozen or halted. Many more people could still be facing cuts under additional planned reductions.

President Donald Trump has explicitly targeted climate- and justice-related programs and funding, but the resulting cuts have gone deep into services communities rely on to survive, like food aid in rural areas or improvements to failing wastewater infrastructure. Farmers have lost grants and support that help keep them going through increasingly volatile weather. Even your favorite YouTube creators may be affected.

We asked those who have lost their federal jobs or funding to tell us about what’s being lost: What was their work providing to communities, and what happens now?

Their stories, reflecting just a small sample of the many people who’ve been affected, illuminate how deep these cuts go, not only into programs explicitly working to reduce emissions, but also into those keeping us safe, healthy, fed, and informed.

Have you been impacted, or know someone who has? We want to hear about it. Message us on Signal at 206-876-3147 or share your story using this form. (Learn more about how to reach us and how we will use your information.)

Sort by topic

All

Disaster recovery

Health and safety

Food access

Historical preservation

Public information

Education

Data and research

Waste and recycling

Energy costs

Disaster recovery

“It offered housing, your food was paid for. I didn’t really have to worry about how I would survive.”

Rachel Suber, former FEMA Corps member | Pennsylvania

Read more

Since January, Rachel Suber had been a member of FEMA Corps, a specialized program of AmeriCorps, the federal national service program, which deploys volunteers to disaster zones to aid in recovery. She’d been assigned to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to help those affected by Hurricane Debby, a tropical cyclone that flooded parts of the Northeast last summer.

As a corps volunteer with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Suber would go into the field to survey damage and help people access federal assistance funding. Back at the office, she would log data about what had been done at site inspections, where the worst damage was, and who had yet to receive assistance.

In April, Suber got the news that her program — and all of AmeriCorps — was being terminated. “We will be demobilized immediately,” she remembers her boss saying. “I’m going to miss you all.” One hundred and thirty FEMA Corps members and some 32,000 AmeriCorps volunteers were out of work.

Suber and her cohort were aware of the changes Trump was making to FEMA and other federal agencies, but the funding for her program was allocated for the year. No one had thought the new administration could take it away.

So far, FEMA’s work in the region continues. But without help from the corps members, Suber said, more work will be put on program managers, slowing the process of getting aid to those who need it.

For Suber, it’s also the end of her path to a career and a way out of rural Pennsylvania, where jobs are scarce. “It offered housing, your food was paid for. I didn’t really have to worry about how I would survive.” With the cancellation of the program, less than four months into what should have been a 10-month assignment, Suber’s dreams of working for FEMA have faded.

— Zoya Teirstein

Health and safety

“People felt like their concerns were real and that they deserved better.”

Caroline Frischmon, graduate research assistant | Mississippi

Read more

Caroline Frischmon had been selected to receive a $1.25 million grant from the Environmental Protection Agency to study air pollution in two Louisiana towns and Cherokee Forest, a subdivision in Pascagoula, Mississippi. The neighborhood, which is near a Chevron refinery, a Superfund site, and a liquefied natural gas terminal, has more than three times the amount of cancer risk the EPA deems acceptable.

The funding was part of EPA’s Science to Achieve Results, or STAR, an initiative that has awarded more than 4,100 grants nationwide since 1995 to support high-quality environmental and public health research. In April, EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin ordered the termination of STAR and other research grants, including some $124 million in funds that had already been promised. Frischmon’s funding evaporated overnight.

As a graduate student at the University of Colorado, Frischmon had set up low-cost air monitors in Cherokee Forest and identified a recurring pattern of short-lived, intense pollution episodes that correlated with resident complaints of burning eyes, sore throats, vomiting, and nausea. The state air quality monitors were capturing average pollution levels but missed short-term spikes that were just as consequential to human health.

“The validation has really led to an activation in the community,” said Frischmon. “People felt like their concerns were real and that they deserved better.”

The $1.25 million EPA grant would have funded a multiyear air quality study and Frischmon’s postdoctoral position at the university. She is now job hunting and searching for smaller grants, but she isn’t optimistic she will find funding on the scale of the EPA grant. For the community, she said, it feels like an abrupt end to tangible progress toward solving their health crisis. “So there’s a lot of sadness over losing that momentum.”

— Naveena Sadasivam

Food access

“Agricultural producers are already living on the fringes of income.”

Matthew O’Malley, agricultural engineer with the Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service | Colorado

Read more

As an agricultural engineer with the Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, or NRCS, Matthew O’Malley’s job was helping farmers and ranchers in northeastern Colorado implement more efficient infrastructure to deal with growing water scarcity. On any given day, that could involve anything from building an irrigation system that cuts down on the amount of water released to feed thirsty crops to designing a retention basin to store excess water produced during rainy periods for use during drier ones.

In February, O’Malley was abruptly fired from his position in a wave of mass layoffs by the Trump administration. By the end of the following month, he’d be invited back to work, temporarily, after a federal court ruled the thousands of laid-off government workers must be reinstated. O’Malley instead elected to take the deferred resignation he was subsequently offered, wary of the volatility. Until September 30, he will remain a federal employee on paper.

Before the mass government firings hit the NRCS offices in northeast Colorado, there were a total of four staffers, O’Malley included, serving as agricultural engineers in the region. Half took the deferred resignation.

“The planning stopped for the projects I was designing overnight,” said O’Malley. “I’m more concerned for the smaller agricultural producers, rather than myself, for the agency. They’re the ones that rely on USDA programs to help them make it through years when there’s crop failure.”

Because of the economic landscape, escalating extreme weather risk, and intensifying water scarcity, farmers’ need for support in the region is at a level O’Malley has never before seen. “Agricultural producers are already living on the fringes of income,” he said. “Helping these producers protect the resources that they have, and allowing them to better utilize them, ultimately helps everyone. We all need to eat.”

— Ayurella Horn-Muller

Photo credit: Courtesy Matthew O’Malley

Health and safety

“The funding just stopped. I’m stuck with this valuable data that not a lot of people have.”

Edgar Villaseñor, advocacy campaign manager for the Rio Grande International Study Center | Texas

Read more

Residents of Laredo, Texas, like people in cities all over the world, endure a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect, whereby roads, sidewalks, and buildings trap heat. For Laredo, this phenomenon only exacerbates already ferocious heat, particularly in lower-income neighborhoods that tend to have fewer trees and green spaces.

Last summer, to better understand how heat affects Laredo’s 260,000 residents, the nonprofit Rio Grande International Study Center partnered with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and enlisted more than 100 volunteers to drive around the city taking temperature readings. Edgar Villaseñor, the center’s advocacy campaign manager, then worked with a company called CAPA Strategies to create a map of heat throughout the city.

Villaseñor wanted more detailed data and an enhanced, interactive map that would not only be easier for residents to navigate, but also help the city council plan interventions, like installing more shade for people waiting at bus stops. He applied for a $10,000 grant through NOAA’s Center for Heat Resilient Communities, which was funded through the Inflation Reduction Act.

The center had planned to work with a range of communities for a year to craft targeted heat action plans, and then to create guides that would help cities around the U.S. build their own heat strategies.

The research center was ready to announce in May that Villaseñor’s nonprofit, along with 14 city governments, had been selected. But the day before the announcement, NOAA instead sent notices that it was defunding the center. “The funding just stopped,” Villaseñor said. “I’m stuck with this valuable data that not a lot of people have.”

Villaseñor said his work won’t stop, even though that $10,000 grant would have gone a long way. “I’m still trying to see what I can do without funding.”

Read more: Funding to protect American cities from extreme heat just evaporated

— Matt Simon

Historical preservation

“You have to make sure you’re not destroying any wetlands, not affecting air pollution … not harming any historical or cultural material.”

Name withheld, National Park Service archaeologist | East Coast

Read more

Archaeology might not be the first profession that comes to mind when you think of the National Park Service. But the federal agency, housed under the Interior Department, needs a whole lot of them — to examine historical artifacts, to oversee excavations, to ensure that on-site construction projects comply with preservation laws.

One federal archaeologist, who asked that their name be withheld for security, worked at a historic East Coast park, combing through a “very long backlog” of 19th-century farm equipment and deciding which samples should be preserved. Storage space is a “very serious problem in archaeology,” they said, and the park service generally lacks the funding to make more room.

The other part of their job was about compliance, ensuring that proposed developments — whether a new water line or a building renovation — adhered to federal laws on environmental and historical impacts. “You have to make sure you’re not destroying any wetlands, not affecting air pollution … not harming any historical or cultural material,” they said.

This worker had been at their post, which was supported by funding via the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, for national parks, just over a year when Trump froze IRA spending. They found out in February that their funding was no longer available, but held on a few more weeks, thanks to extra funds cobbled together by their supervisor. By the time a federal judge ordered the IRA money unfrozen, they had already accepted another archaeology job. With all the funding uncertainty — compounded by layoffs and buyouts that have reduced park service staff by 24 percent since the beginning of the year — they said the vacancy they left is unlikely to be filled.

Without archaeologists, the worker said, simple maintenance projects could be stalled or improperly managed. “They will either not be able to do that or they will do the projects without compliance and destroy very important sites to our shared history.”

— Joseph Winters

Public information

“The team was part of a nationwide push to build trust with communities so that we could better understand what they needed so that the government could serve communities better.”

Amelia Hertzberg, environmental protection specialist at the EPA | Virginia

Read more

When EPA employees engage with communities affected by an environmental disaster, they often face angry and distrustful crowds. These communities are often the ones that have been historically neglected by the federal government, and residents may be dealing with serious health problems. Amelia Hertzberg was training staff to stay calm and engage productively in those situations.

Hertzberg began working at the EPA in 2022, first as a research fellow and then as a full-time employee in the community engagement department within the environmental justice office. She initially helped communicate the risk that ethylene oxide, a toxic chemical used in sterilization, poses to communities. Then, as the EPA ramped up its efforts to work with historically disadvantaged communities during the Biden administration, she began conducting trainings to help staff understand how to work directly with communities facing trauma.

“Again and again, I heard, ‘I don’t know how to deal with people’s emotions,’” recalled Hertzberg. “‘There’s things that I can’t help them with that make me upset, and I don’t know what to do with my feelings of stress or theirs.’ And so I was trying to meet that need.”

In April, the Trump administration announced that it would lay off 280 employees from the EPA’s environmental justice office and reassign an additional 175 people, effectively ending the office altogether. The announcement came after a February notice that placed 170 staff members, including Hertzberg, on administrative leave. Just two of the 11 people on Hertzberg’s community engagement team stayed on, and most of their programs have been canceled. Hertzberg is still on administrative leave.

“The environmental justice office is the EPA’s triage unit,” Hertzberg said. “The team was part of a nationwide push to build trust with communities so that we could better understand what they needed so that the government could serve communities better.”

— Naveena Sadasivam

Disaster recovery

“We were in constant contact with survivors who were very upset.”

Julian Nava-Cortez, former California Emergency Response Corps member | California

Read more

After devastating fires tore through Los Angeles in January, Julian Nava-Cortez traveled from northern California to assist survivors at a disaster recovery center near Altadena, where the Eaton Fire had nearly destroyed the entire neighborhood. People arrived in tears, overwhelmed and angry, he said.

“We were the first faces that they’d see,” said Nava-Cortez, at the time a member of the California Emergency Response Corps, one of two AmeriCorps programs that sent workers to assist in fire recovery. He guided people to the resources they needed to secure emergency housing, navigate insurance claims, and go through the process of debris removal. He sometimes worked 11-hour, emotionally draining shifts, listening to stories of what survivors had lost. “We were in constant contact with survivors who were very upset,” he said. What kept him going, he said, was how grateful people were for his help.

Volunteers like Nava-Cortez have helped 47,000 households affected by the fires, according to California Volunteers, the state service commission under the governor’s office. But in late April, Nava-Cortez and his team at the California Emergency Response Corps were suddenly placed on leave. Another program helping with the recovery in L.A., the California AmeriCorps Disaster Team, also abruptly shut down as a result of cuts to AmeriCorps.

At the end of April, two dozen states, including California, sued the Trump administration over the cuts to AmeriCorps, alleging that DOGE illegally gutted an agency that Congress created and funded. In June, a federal judge temporarily blocked the cuts in those jurisdictions.

The nonprofit that sponsored Nava-Cortez and his fellow AmeriCorps members offered them temporary jobs 30 days after they were put on leave, though many had already found other work. Nava-Cortez took the offer and worked for another month before the money ran out, but was unable to finish his term, which was supposed to go through the end of July. Since then, he’s been on unemployment, unable to find work ahead of moving to San Jose for school this fall.

Read more: After disasters, AmeriCorps was everywhere. What happens when it’s gone?

– Kate Yoder

Public information

“There might just be one day you log onto YouTube and none of your favorite creators are there anymore.”

Emily Graslie, creator of The Brain Scoop YouTube channel | Illinois

Read more

Emily Graslie creates YouTube videos explaining all kinds of scientific research in fun, easy-to-understand ways. On her channel, The Brain Scoop, she’s covered topics ranging from fossils to rats, often partnering with libraries or museums to tell the story of their work.

Her next project was going to be with the National Institutes of Health, or NIH, creating videos for The Brain Scoop explaining some of the organization’s groundbreaking medical research. She’d spent a year developing the series with her NIH partners and was supposed to be on campus at the NIH in January of this year to begin shooting. Instead, she received an email telling her that the project was on hold until further notice.

The acting Health and Human Services secretary had issued a memo within the first days of the Trump administration halting nearly all external communications. “Because I’m considered a member of the media, I was unable to communicate with these people I had been partnering with for over a year,” she said.

Through an informal meeting with one of her collaborators, she learned that the project was effectively canceled — and with it, money Graslie had been counting on for her livelihood, a slate of planned videos, and what she saw as important work educating viewers about lifesaving science.

Many people may not realize, Graslie said, that the federal funding that supports scientific research and programming at museums also often covered contracts with independent creators like herself, to help communicate the work to the public.

“One of the most significant things that The Brain Scoop did is just share the different kinds of work that happens at nature centers and museums across the country,” she said. The loss is “just a limiting of people’s understandings of what they’re capable of, who they want to be when they grow up, how they see the world around them.”

Read more: Even your favorite YouTube creators are feeling the effects of federal cuts

— Claire Elise Thompson

Photo credit: Julie Florio

Education

“It’s a huge loss for the 1,000 students that we work with.”

Sky Hawk Bressette, former restoration educator for the city of Bellingham’s Parks and Recreation Department | Washington

Read more

For three years, Sky Hawk Bressette served as a restoration educator in the parks department in Bellingham, Washington. With a fellow member of the Washington Service Corps, he worked with the school district to teach nearly every fifth grader in the city about native plants.

Their free lessons — aligned with state science standards — showed kids how to identify plants, spot invasive species, and understand the role of native flora in the local ecosystem. They also hosted “mini-work parties,” where students got their hands dirty pulling weeds and planting native trees and shrubs, learning how to care for the land around them. “All of our teachers that we work with absolutely love what we do,” Bressette said.

But that work is now on hold — possibly for good — after federal cuts to AmeriCorps funding. In late April, Bressette received notice that he was being put on unpaid leave, effective immediately. “It’s weird, it’s sad, it’s scary,” he said. “I really do love what I do.” After a judge struck down the cuts in June, he briefly returned to work until his term ended in July. By then, he had already missed the end of the school year, the busiest time for working with students.

Outside the classroom, Bressette helped organize volunteer work parties that planted thousands of trees and hauled dump trucks’ worth of invasive species out of local parks in Bellingham. But with no guarantee for future funding, the city is eliminating Bressette and his colleague’s positions. That means that the environmental education lessons are likely shut down for at least the next year, Bressette said, while the city weighs whether to bring them back.

“It’s a huge loss for the 1,000 students that we work with in our city alone,” he said.

— Kate Yoder

Photo credit: Allison Greener Grant

Disaster recovery

“I lost my job from the fire and here again from this political climate.”

Ryanda Sarraude, former office administrator at Roots Reborn | Hawai‘i

Read more

In the summer of 2023, Ryanda Sarraude was working as an account manager at a human resources company serving local businesses in West Maui. When massive wildfires shut down tourism and contaminated the water in her neighborhood, Sarraude was forced to move out of her house and her company laid her off because so many local businesses had shut down.

Months later, a job opened up at Roots Reborn, a nonprofit organization serving recent immigrants on Maui, and Sarraude was hired as an office administrator. The role was funded by a federal program aimed at helping disaster survivors get back on their feet.

Lāhainā is home to many immigrant communities from the Philippines, Latin America, and the Pacific islands. Many families who didn’t have bank accounts had hidden cash in their homes that burned down, so the nonprofit launched a financial education workshop. Health issues like depression and asthma shot up in the wake of the fires, so Roots Reborn partnered with Kaiser to help people enroll in health insurance by providing guidance and Spanish interpreters.

“I wanted to help people,” Sarraude said. “It was very rewarding.” Then in February, Sarraude found out the federal funding for her position had evaporated amid the Trump administration’s crackdown on government spending. Sarraude was among 131 Maui workers who lost their jobs almost overnight across 27 different organizations, even though the nonprofit overseeing their program had expected the federal funding to be renewed for several more months. Around 5 p.m. on a Sunday, Sarraude was told not to show up to work the next day.

“I lost my job from the fire and here again from this political climate,” Sarraude said. She scrambled to apply to other gigs and a few weeks later landed a lower-paying role as a web administrator for a local business. She likes her new job, but is relying on Medicaid and food stamps and is nervous about what Republicans’ decision to cut funding for those programs will mean for her access to food and health care.

— Anita Hofschneider

Food access

“We want kids to understand where their food comes from. We want them to be able to have that experience of growing their own food.”

Erica Krug, farm-to-school director at Rooted | Wisconsin

Read more

First established some 25 years ago in a historically underserved neighborhood in Madison, Wisconsin, that has long struggled with access to healthy food, Mendota Elementary’s garden is now a part of the school’s curriculum — students plant produce, which is shared with local food pantries. Come summer, the garden opens to the surrounding community to harvest crops like garlic, tomatoes, zucchini, collards, and squash.

“They’re mending the soil one week, and then the next week they’re going to start to see these little seedlings pop through the soil,” said Erica Krug, farm-to-school director at Rooted, a nonprofit that helps oversee the garden.

In January, the Rooted team applied for a $100,000 two-year grant through the USDA’s Patrick Leahy Farm to School program, intended to provide public schools with locally produced fresh vegetables as well as food and agricultural education, a grant they’d received in past cycles. The program was created in 2010, and Congress allocated $10 million for it this fiscal year.

In March, Rooted received an email announcing the cancellation of this year’s grant program “in alignment with President Donald Trump’s executive order Ending Radical and Wasteful Government and DEI Programs and Preferencing.”

The loss of the funds is “so upsetting,” said Krug, and the reasoning provided, she continued, is “ridiculous.” In prior years, Krug said, “we were being asked ‘What are you doing to address equity? To address diversity? How are you making sure your project is for everyone?’ And now we’re going to be penalized for talking about that.”

The team at Rooted is now working overtime to find other funding sources to continue the work. “We’re not ready to say, without this funding, that we’re going to abandon this program, because we believe so strongly in it,” she said.

Read more: Trump’s latest USDA cuts undermine his plan to ‘Make America Healthy Again’

— Ayurella Horn-Muller

Public information

“It’s our duty to help protect people and have them understand the risks and understand the tools they can use.”

Tom Di Liberto, former public affairs specialist at NOAA | Washington, D.C.

Read more

For Tom Di Liberto, a climate scientist-turned communications specialist, working at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration fulfilled a dream he had held since elementary school. It was also, he believed, fulfilling an essential function for the American people.

“I was incredibly proud of being able to work with different communities to help them understand the resources that NOAA has, so they can properly use them in the decisions that they make,” he said. That included working with doctors to help them make better use of the agency’s climate and weather data to understand the shifting probabilities of various medical diagnoses, and reaching out to faith communities to discuss how they could use their gathering spaces to help residents weather extreme heat and other impacts.

“Those sorts of activities are all done now,” Di Liberto said.

He lost his job at NOAA on February 27, along with hundreds of his colleagues targeted by the Department of Government Efficiency. By court order, he was rehired in March, but then fired once again in April, he said, when the judge let that order expire. Di Liberto is now working as a media director for the nonprofit Climate Central.

These workforce reductions have hampered the agency’s research capacity, as well as its ability to share that critical research with the public, Di Liberto said.

“I think people don’t know that NOAA is beyond just your weather forecast — that NOAA works directly with communities to help build resilience plans for extremes,” he said, adding that, under the new Trump administration, the bulk of that community work “is either threatened or come to a screeching halt.”

One of the communication projects he was proudest of was launching NOAA’s first animated series — a creative tool to teach climate and weather science to kids. “I have all the episodes downloaded personally on my computer — so if they ever take it down, they’ll go right back up,” he said.

— Claire Elise Thompson

Food access

“This was for important work, representing small- and medium-sized farms, and also trying to leverage the food economy to go faster and further.”

Anthony Myint, cofounder of Zero Foodprint | Oregon

Read more

Anthony Myint’s nonprofit, Zero Foodprint, works across the public and private sectors, sourcing and awarding grants that incentivize the adoption of better farming practices. His goal is to support farmers who are working to build healthier soil, which increases the food system’s resilience to supply chain shocks, improves water quality, and stores carbon.

A chef-turned-entrepeneur, Myint founded the nonprofit after seeing firsthand how important farming practices are to ensuring a more sustainable planet.

In April, Myint learned that a $35 million USDA grant his team was a subawardee on had been suddenly canceled. The nonprofit had been awarded roughly $7 million in 2023 as part of a five-year program to help hundreds of farmers and agricultural projects across the country implement production techniques to improve soil quality and crop resilience.

Myint’s team had been helping award and distribute the funding to roughly 400 projects, like a group of almond producers in California’s Central Valley working to establish composting and nutrient management practices. By the time the project was terminated, only about $800,000 had been awarded to around 50 projects. “We were ramping up to the bulk of work this spring,” said Myint.

The loss of the funding left “a really big gap.” “We’re using reserves and philanthropy and other things to maintain and sort of shift our growth onto that new available capacity instead of hiring,” said Myint. “We’re essentially frozen.”

Myint saw the USDA funds as a vital — and successful — incentive to move farms and companies to more sustainable practices. “This was for important work, representing small- and medium-sized farms, and also trying to leverage the food economy to go faster and further … and every single project was negatively impacted.”

— Ayurella Horn-Muller

Data and research

“It’s just about having the info that policymakers need to make decisions. Without it, we’re flying blind.”

Shane Coffield, former science and technology policy fellow at AAAS | Washington, D.C.

Read more

Every year, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, or AAAS, places roughly 150 fellows at various federal agencies. Established in 1973, the Science and Technology Policy Fellowships program provides a pipeline for scientists to enter public service.

Shane Coffield was one of six fellows placed at the EPA last September. As a researcher with a doctorate in Earth system science, Coffield specializes in various remote sensing techniques and was tasked with working on the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory, an annual accounting of the country’s emissions, which provides a baseline for climate policy and has been published since the early 1990s. The U.S. is also obligated to provide the emissions data every year to a United Nations body that oversees international climate negotiations.

In April, the agency missed a deadline to release the data, even though Coffield and others at the EPA had finished the report. That month, the agency also terminated its agreement with AAAS that allowed Coffield and five other fellows to work there, four months before their positions were due to end. This year’s report was never officially released, although the information was made public through a FOIA request. It’s unclear if the agency will produce the inventory in 2026.

The greenhouse gas inventory is “policy agnostic,” said Coffield. “It’s just about having the info that policymakers need to make decisions. Without it, we’re flying blind.”

During his time at the agency, Coffield also helped other countries such as El Salvador and South Africa build their own greenhouse gas inventories. When the Trump administration instructed staff to drop all foreign aid work in late January, Coffield could not engage with his international counterparts anymore.

— Naveena Sadasivam

Photo credit: Courtesy Shane Coffield

Education

“There’s a huge need to increase climate literacy, even here in NYC, and now there will be fewer opportunities for it.”

Rafi Santo, principal researcher at Telos Learning | New York

Read more

Last year, Rafi Santo helped launch an education project that aimed to connect young people from climate-impacted communities with scientists and artists to co-create interactive public exhibits. The program — a collaboration between Pratt Institute, Beam Center, and Santo’s organization, Telos Learning — was funded by a National Science Foundation grant focused on bringing STEM learning to new settings and audiences.

“We have an incredible need to both have the general public understand the mechanisms behind climate change, but also understand what they can do about it,” Santo said. The pop-up exhibits would aim to build climate literacy and awareness of local adaptation efforts in New York.

Santo, who studies educational frameworks, also wanted to research the significance of giving young people a seat at the table — “helping to better understand how those most affected by the crisis can be meaningfully contributing to its response.”

The group received around 400 applications. But on April 25, the day they planned to send acceptance letters, they instead found out that their grant had been terminated. The National Science Foundation had announced that it was terminating awards “that are not aligned with program goals or agency priorities.” Hundreds of research grants were canceled.

Santo’s program was specifically focused on young people in communities of color, which “probably made an easy keyword search for them,” he said.

It was devastating to see so much passion and so many stories that now won’t get to be shared, Santo said, as well as the loss to the public of the opportunity to engage with climate topics in new ways. For him personally, this would also have been his first climate research initiative — something he had wanted to pursue professionally ever since he experienced a devastating heat wave in 2021. “It feels especially heartbreaking,” he said. “I now don’t know how I might contribute or what kind of projects I might do that can contribute to this work.”

— Claire Elise Thompson

Waste and recycling

“Composting, for me, is a lot about community.”

Ella Kilpatrick Kotner, compost program director at Groundwork RI | Rhode Island

Read more

“Composting, for me, is a lot about community,” said Ella Kilpatrick Kotner, who leads a composting program at Groundwork RI, a nonprofit in Providence, Rhode Island, “and treating this thing that many people think of as a waste as a resource to be cherished and handled with care and turned into something beautiful that we can then reuse to grow more food.”

Every day, her team of three bikes through the city, collecting food scraps from hundreds of households. Back at a community garden, they mix it all with dry leaves and wood shavings, while sifting out pieces of plastic and even the occasional fork, transforming the waste into a nitrogen-rich conditioner for the soil. That compost is available to those enrolled in Groundwork RI’s subscription service to use in home gardens, yards, or urban farms.

In December, Groundwork RI was one of nine organizations included in an $18.7 million grant awarded to the Rhode Island Food Policy Council through the Community Change Grants Program, a congressionally authorized program to support community-based organizations addressing environmental justice challenges.

A portion of the three-year funding was intended to help Groundwork RI expand its collection service to neighboring cities, build a bigger compost hub, renovate its greenhouse and pay-what-you-can farm stand, and add composting bin systems to more local community gardens. It also would have made it possible for Kilpatrick Kotner’s team to launch a free food-scrap collection pilot with the city.

During Trump’s first term, his administration committed to ambitious food waste reduction goals. This time, after months of uncertainty, the partners involved in the Rhode Island food-waste project learned in May that their grant was terminated. The EPA’s official notice, shared with Grist, informed the grantees that their project was “no longer consistent” with the federal agency’s funding priorities and therefore nullified “effective immediately.”

Read more: An $18M grant would have drastically reduced food waste. Then the EPA cut it.

– Ayurella Horn-Muller

Photo credit: Charlotte Canner / Groundwork RI

Health and safety

“We have wastewater infrastructure that is old. It’s critical that we do the work to replace this.”

Sheryl Sealy, assistant city manager for Thomasville | Georgia

Read more

Thomasville, Georgia, has a water problem. Its treatment system is far out of date, posing serious health and environmental risks — not just the risk of sewage overflowing into homes and waterways, but resulting respiratory issues as well.

“We have wastewater infrastructure that is old,” said Sheryl Sealy, the assistant city manager for this city of 18,881 near the Florida border. “It’s critical that we do the work to replace this.”

Earlier this year, Thomasville and its partners were awarded a nearly $20 million Community Change grant from the EPA to make the long-overdue wastewater improvements, build a resilience hub and health clinic, and upgrade homes in several historic neighborhoods.

“The grant itself was really a godsend for us,” Sealy said.

Thomasville has a history of heavy industry that has led to high risks from toxic air pollution, and the city qualified for the Biden administration’s Justice40 initiative, which prioritized funding for disadvantaged communities.

In early April, as the EPA canceled grants for similar projects across the country, federal officials assured Thomasville that its funding was on track. Then, on May 1, the city received a termination notice. “We felt, you know, a little taken off guard when the bottom did let out for us,” said Sealy.

Under the Trump administration, the EPA has canceled or interrupted hundreds of grants aimed at improving health and severe weather preparedness because the agency “determined that the grant applications no longer support administration priorities,” according to an emailed statement to Grist.

Thomasville, along with other cities that have had grants terminated, is appealing the decision.

Read more: Trump cuts hundreds of EPA grants, leaving cities on the hook for climate resiliency

— Emily Jones

Disaster recovery

“I come home and I’m exhausted and I’ve got cat poop all over me, but it was just such a rewarding feeling.”

Susan Caballero, former humanitarian at the Maui Humane Society | Hawai‘i

Read more

Susan Caballero wasn’t living in Lāhainā the day that the West Maui town burned down on August 8, 2023. But the devastating wildfire brought the island’s tourism industry to a screeching halt. A day later, Caballero was laid off from her job as a salesperson at a boutique handicrafts store 45 minutes away.

Within months, federal funding to help wildfire survivors poured in and the Biden administration released a federal grant specifically to help displaced workers. It was through that funding that Caballero got hired at the Maui Humane Society. Her job was caring for cats: feeding them, giving them medicine, persuading families to adopt them.

There are 40,000 stray cats on Maui that need homes, about one cat for every four people living on the island. Residents often abandon their cats because there’s so little pet-friendly housing. It’s a massive challenge with terrible environmental consequences: Parasites in feral cat poop contaminate the ocean, killing endangered monk seals. Caballero felt proud using her sales skills to persuade families to take the creatures home, once successfully adopting out a 20-year-old feline.

“It’s just an amazing feeling, I come home and I’m exhausted and I’ve got cat poop all over me, but it was just such a rewarding feeling,” Caballero said.

In February, Caballero was hospitalized after a moped accident. She was lying in her hospital bed when she learned that she was out of a job. The state of Hawaiʻi had expected the federal grant supporting her position and 130 others to be renewed at least through September, but in February the state learned that, at best, the new administration would only offer half of what had been requested. Confronted with uncertain funding, the state shut down the program.

“I was only making $23 an hour. I’m 58 years old,” she said. “I have to laugh because that’s all I can do and that hurts.”

Five months later, she’s still physically recovering and isn’t sure what’s next. Her rent just went up to $1,582 per month, and her disability check will no longer cover it.

— Anita Hofschneider

Food access

“This is a blow to our entire food system.”

Robbi Mixon, executive director of the Alaska Food Policy Council | Alaska

Read more

Three years ago, the Alaska Food Policy Council, or AFPC, partnered with a handful of other food and farming groups to apply for the Regional Food Business Center program — a new initiative launched by the Biden administration to expand and build localized food supply chains. In May 2023, it was selected by the USDA as a sub-awardee to help create one of 12 national centers established through the initiative, leading the Alaska arm of the Islands and Remote Areas Regional Food Business Center.

[Content truncated due to length...]

From Grist via this RSS feed

“For the first time in history, the ICJ has spoken directly about the biggest threat facing humanity,” Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s climate change minister, said of the ruling. He is seen here in court before the decision was handed down.

John Thys / AFP via Getty Images

“For the first time in history, the ICJ has spoken directly about the biggest threat facing humanity,” Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s climate change minister, said of the ruling. He is seen here in court before the decision was handed down.

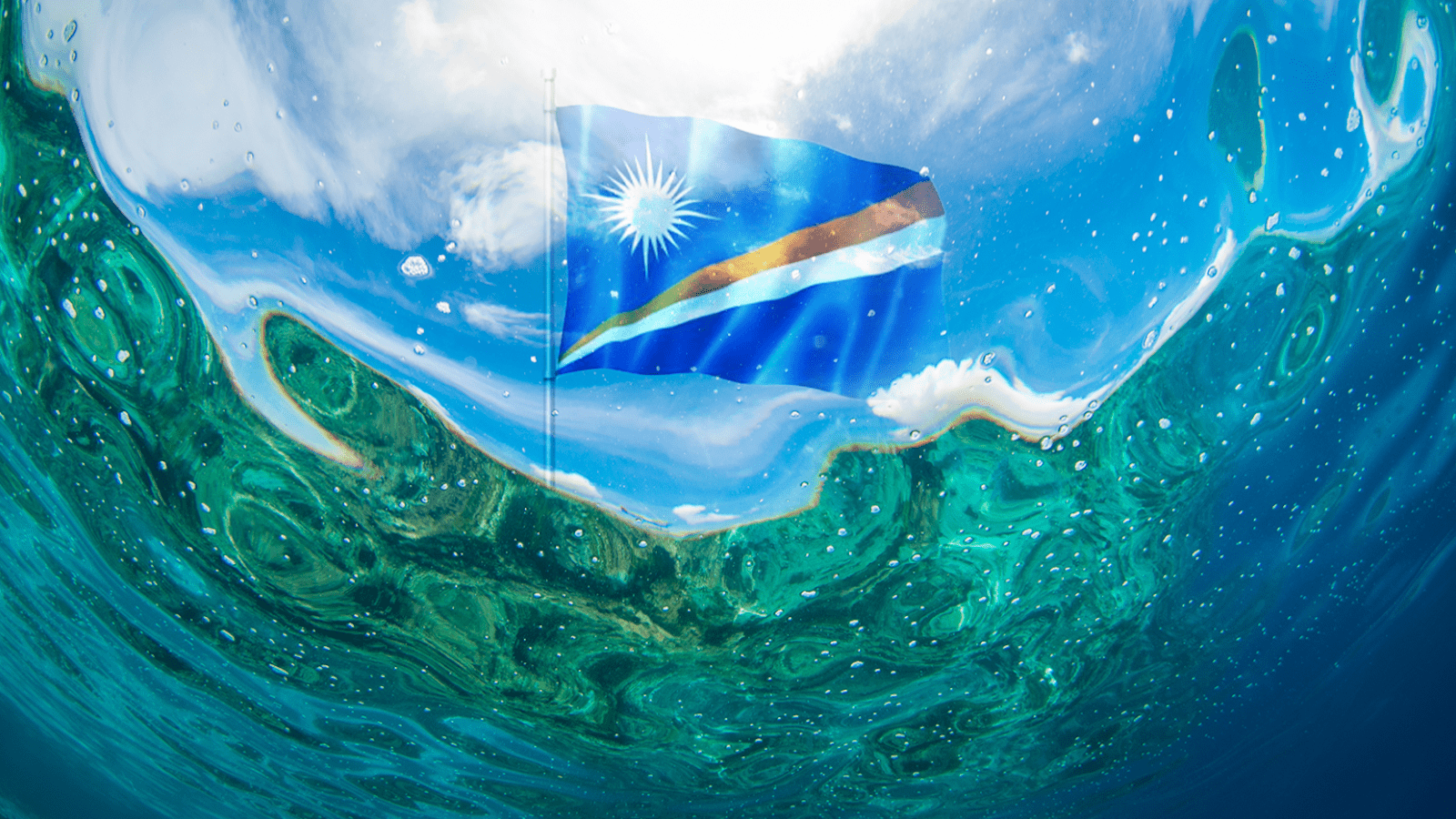

John Thys / AFP via Getty Images Inside the Marshall Islands’ life-or-death plan to survive climate changeJake Bittle

Inside the Marshall Islands’ life-or-death plan to survive climate changeJake Bittle Farmworkers in southern California take a water break in the middle of a heatwave.

ETIENNE LAURENT / AFP via Getty Images

Farmworkers in southern California take a water break in the middle of a heatwave.

ETIENNE LAURENT / AFP via Getty Images A farmer loads plants on a truck at an ornamental plant nursery in Homestead, Florida, some 40 miles north of Miami. CHANDAN KHANNA / AFP via Getty Images

A farmer loads plants on a truck at an ornamental plant nursery in Homestead, Florida, some 40 miles north of Miami. CHANDAN KHANNA / AFP via Getty Images Laura Mallonee / Grist

Laura Mallonee / Grist A student holds up a plant “plug” dug from the prairie. It will be transplanted at a restoration site managed by students at St. Mark’s School of Dallas, 30 minutes north. Laura Mallonee / Grist Laura Mallonee / Grist

A student holds up a plant “plug” dug from the prairie. It will be transplanted at a restoration site managed by students at St. Mark’s School of Dallas, 30 minutes north. Laura Mallonee / Grist Laura Mallonee / Grist Laura Mallonee / Grist

Laura Mallonee / Grist Narrow-leaved coneflowers dapple a prairie on a late spring morning in southern Dallas. Laura Mallonee / Grist

Narrow-leaved coneflowers dapple a prairie on a late spring morning in southern Dallas. Laura Mallonee / Grist

Native plant grower Randy Johnson sells seedlings during Native Plants and Prairies Day on May 3, 2025, at the Bath House Cultural Center at White Rock Lake in Dallas. Laura Mallonee / Grist

Native plant grower Randy Johnson sells seedlings during Native Plants and Prairies Day on May 3, 2025, at the Bath House Cultural Center at White Rock Lake in Dallas. Laura Mallonee / Grist

Botanist Canaan Sutton, in orange, gives a tour of a prairie at White Rock Lake in Dallas. The lake is home to 16 fragmented parcels of remnant prairie encompassing roughly 250 acres. Laura Mallonee / Grist

Botanist Canaan Sutton, in orange, gives a tour of a prairie at White Rock Lake in Dallas. The lake is home to 16 fragmented parcels of remnant prairie encompassing roughly 250 acres. Laura Mallonee / Grist Students fill a bucket with plants from a prairie expected to be demolished. The rescued plants are covered in soil and kept moist until transplant. Laura Mallonee / Grist

Students fill a bucket with plants from a prairie expected to be demolished. The rescued plants are covered in soil and kept moist until transplant. Laura Mallonee / Grist Max Yan, a senior at St. Mark’s School, sells plants grown by its prairie club during Native Plants and Prairies Day at White Rock Lake in Dallas. Laura Mallonee / Grist

Max Yan, a senior at St. Mark’s School, sells plants grown by its prairie club during Native Plants and Prairies Day at White Rock Lake in Dallas. Laura Mallonee / Grist

Excess seaweed overtaking shellfish gear on Baywater Shellfish Farm in Hood Canal, Washington. Sarah Collier

Excess seaweed overtaking shellfish gear on Baywater Shellfish Farm in Hood Canal, Washington. Sarah Collier

Concertgoers wander around the Reverb eco-village at Dave Matthews’ show at the Northwell at Jones Beach Theater.

Zack O’Malley Greenburg

Concertgoers wander around the Reverb eco-village at Dave Matthews’ show at the Northwell at Jones Beach Theater.

Zack O’Malley Greenburg Coldplay performs at a Music of the Spheres tour stop in Las Vegas in June. The tour and album name references planets and outer space. Ethan Miller / Getty Images

Coldplay performs at a Music of the Spheres tour stop in Las Vegas in June. The tour and album name references planets and outer space. Ethan Miller / Getty Images Billie Eilish performs onstage at Lollapalooza in 2023 in Chicago. Michael Hickey / Getty Images for ABA

Billie Eilish performs onstage at Lollapalooza in 2023 in Chicago. Michael Hickey / Getty Images for ABA

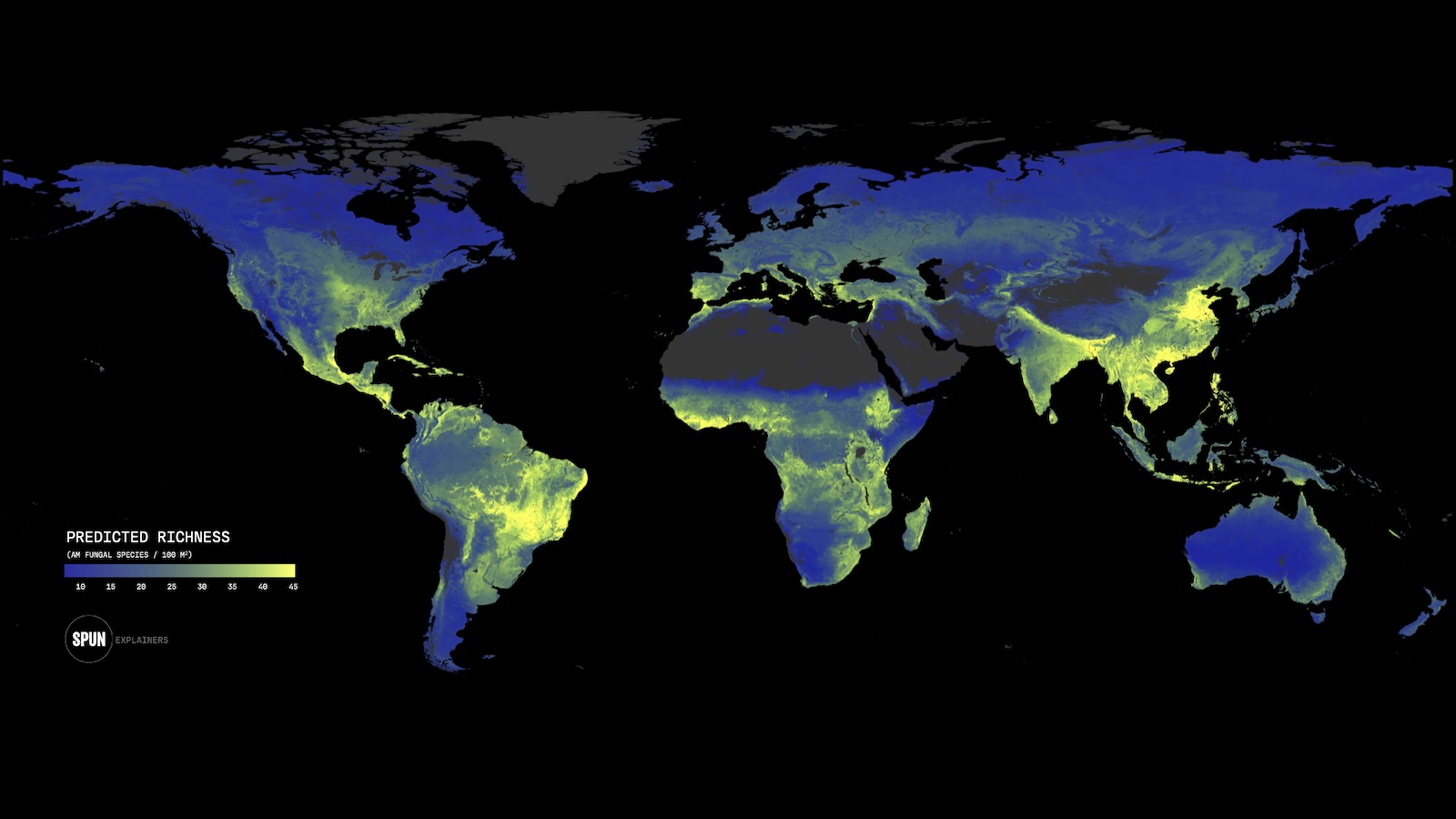

Mycorrhizal fungi in Italy’s Apennine Mountains Seth Carnill

Mycorrhizal fungi in Italy’s Apennine Mountains Seth Carnill SPUN

SPUN SPUN

SPUN Scientists taking samples in Tierra del Fuego, Chile

Mateo Barrenengoa

Scientists taking samples in Tierra del Fuego, Chile

Mateo Barrenengoa

Greenbacker’s 20-megawatt “Albany 1” solar project, in Albany County, New York.

Courtesy of Greenbacker Renewable Energy Company

Greenbacker’s 20-megawatt “Albany 1” solar project, in Albany County, New York.

Courtesy of Greenbacker Renewable Energy Company

Robyn Beck / AFP via Getty Images

Chapter

Robyn Beck / AFP via Getty Images

Chapter Activists protest against the Dakota Access pipeline near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in August 2016. James MacPherson / AP Photo

Activists protest against the Dakota Access pipeline near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in August 2016. James MacPherson / AP Photo Standing Rock Sioux Chairman Dave Archambault poses for a photo on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in 2016. James MacPherson / AP Photo

Standing Rock Sioux Chairman Dave Archambault poses for a photo on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in 2016. James MacPherson / AP Photo More than a thousand people gather at an encampment near North Dakota’s Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in September 2016.

James MacPherson / AP Photo

More than a thousand people gather at an encampment near North Dakota’s Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in September 2016.

James MacPherson / AP Photo

Dogs held by private security guards lunge at protestors attempting to stop the bulldozing of land for the Dakota Access pipeline on September 3, 2016. Robyn Beck / AFP via Getty Images

Dogs held by private security guards lunge at protestors attempting to stop the bulldozing of land for the Dakota Access pipeline on September 3, 2016. Robyn Beck / AFP via Getty Images Greenpeace representatives talk with reporters on March 19 outside the Morton County Courthouse in Mandan, North Dakota. Jack Dura / AP Photo

Greenpeace representatives talk with reporters on March 19 outside the Morton County Courthouse in Mandan, North Dakota. Jack Dura / AP Photo

Ebony Twilley Martin, then co-executive director of Greenpeace USA, speaks during a “Stop Dirty Banks” rally and protest in 2023. Alex Brandon / AP Photo

Ebony Twilley Martin, then co-executive director of Greenpeace USA, speaks during a “Stop Dirty Banks” rally and protest in 2023. Alex Brandon / AP Photo

Kelcy Warren, CEO of Energy Transfer Partners, at a panel on the future of pipeline infrastructure in March 2018 in Houston. Karen Warren / Houston Chronicle via Getty Images

Kelcy Warren, CEO of Energy Transfer Partners, at a panel on the future of pipeline infrastructure in March 2018 in Houston. Karen Warren / Houston Chronicle via Getty Images

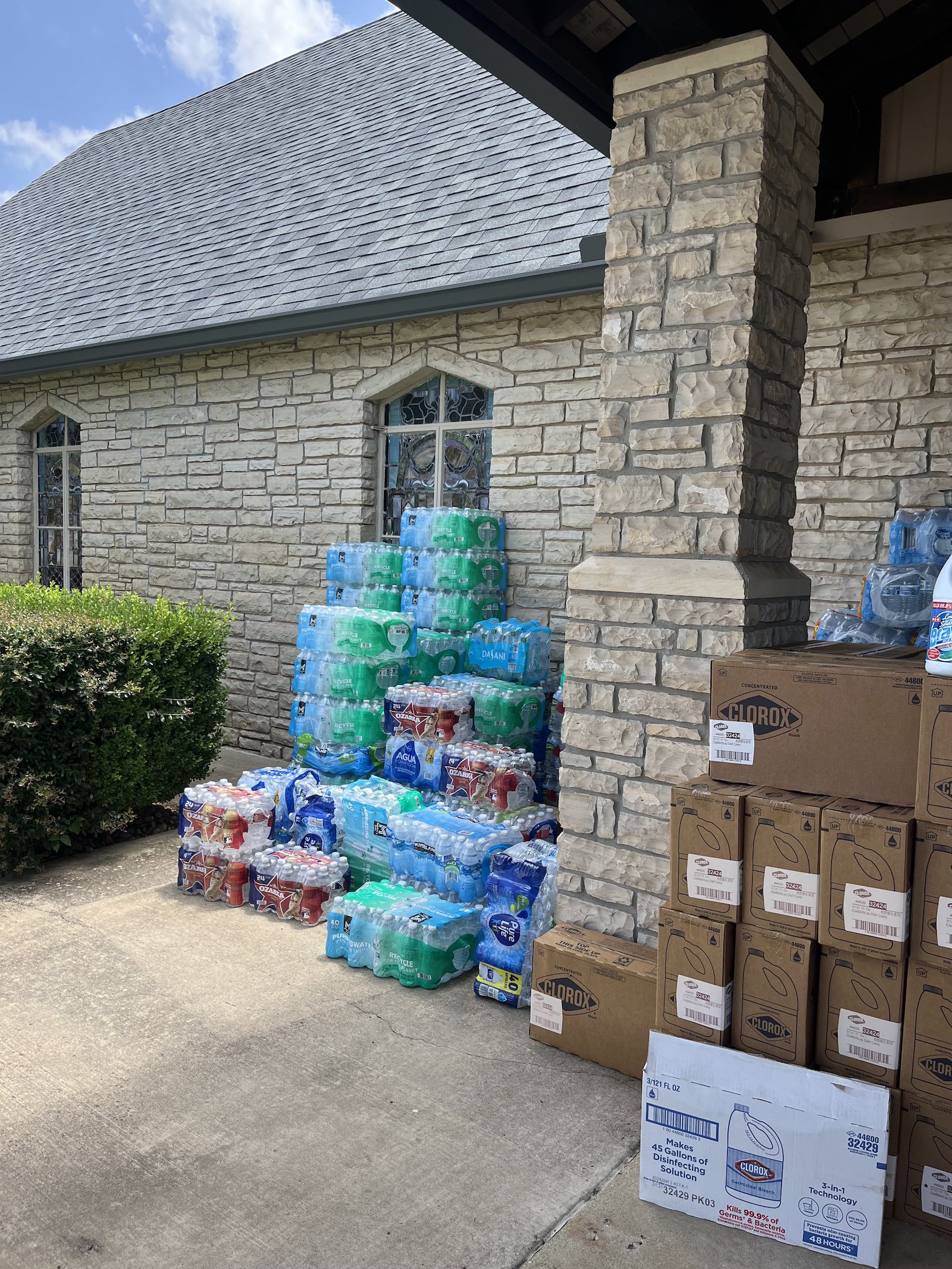

A tow truck aids cleanup efforts in Hunt, Texas, on July 16, 2025. Naveena Sadasivam / Grist

A tow truck aids cleanup efforts in Hunt, Texas, on July 16, 2025. Naveena Sadasivam / Grist

LeAnn Levering wipes down furniture with vinegar to save it from mold.

Naveena Sadasivam / Grist

LeAnn Levering wipes down furniture with vinegar to save it from mold.

Naveena Sadasivam / Grist

Stacks of relief supplies in Hunt, Texas, on July 16, 2025. Naveena Sadasivam / Grist

Stacks of relief supplies in Hunt, Texas, on July 16, 2025. Naveena Sadasivam / Grist

Kevin Carter/Getty Images

Kevin Carter/Getty Images Crops at Featherbed Lane Farm in upstate New York.

Courtesy of Featherbed Lane Farm

Crops at Featherbed Lane Farm in upstate New York.

Courtesy of Featherbed Lane Farm