In 2019, Susan Bowlus got a text from a friend that caught her off guard. “I’ve been watching the coverage on the Golden State Killer,” her friend wrote, referring to the California serial killer who’d been arrested in 2018.

The killer’s name was Joseph DeAngelo, a cop-turned-criminal who’d broken into homes to rape and kill people during the 1970s and 1980s. He was finally caught in Sacramento County, thanks to DNA evidence and a genealogy website. Soon, he’d be prosecuted. “It’s so creepy and I feel weird asking you about this,” the friend continued, but “I remember you telling me about an assault you had.”

Forty years earlier, when Bowlus was 22, a man had entered her Sacramento-area house while she was sleeping and spent hours attacking and violating her. Police never identified him. As she tuned in to the coverage of DeAngelo’s arrest, she grew unsettled: Other confirmed survivors were describing rapes that seemed eerily similar to what she’d experienced. And DeAngelo had lived just a short drive away from her. Was it a coincidence?

Bowlus, who’d long yearned for some resolution to her case, reached out to the Sacramento County district attorney’s and sheriff’s offices, asking for the old crime report. If DeAngelo were the culprit, it would be too late to participate in his trial, but she wanted to know one way or the other and hoped getting an answer would help her heal. “It sounded like that bastard DeAngelo for sure,” retired Sacramento Sheriff’s Detective Richard Shelby, who searched for the Golden State Killer during the 1970s, told me when I described Bowlus’ assault.

Video

The Golden State Killer Story Police Don't Want You to Hear

https://youtu.be/oCkmSxZksBg

DeAngelo’s arrest and conviction made national headlines, framed as long-awaited justice for the dozens of people he raped. He was sentenced in August 2020 to life without parole. “It’s just so nice to have closure and to know he’s in jail,” Jane Carson-Sandler, who survived a 1976 assault, told the Associated Press after DeAngelo’s arrest.

“The nightmare has ended,” Carol Daly, one of the original detectives working the case in Sacramento, said in a statement on behalf of another victim.

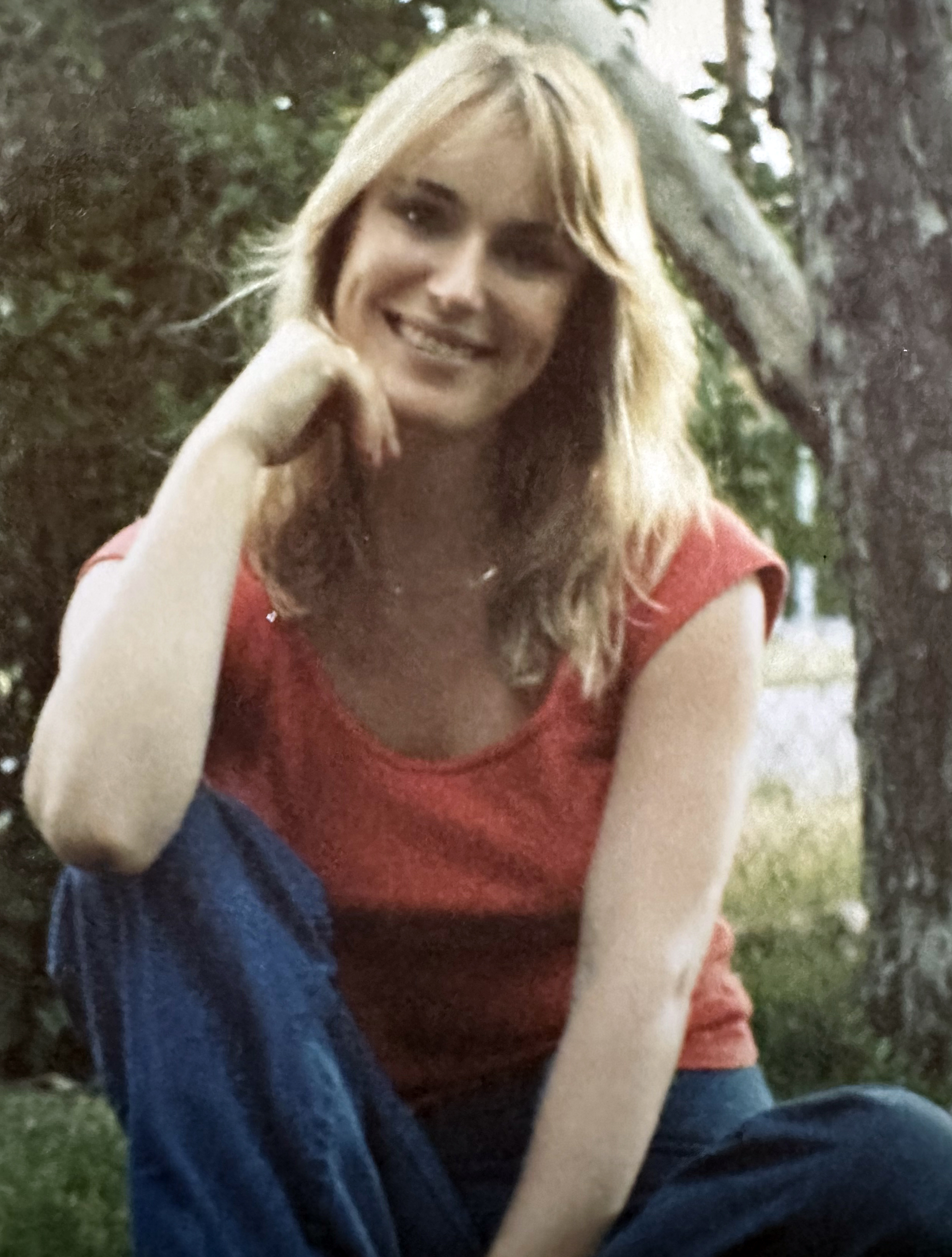

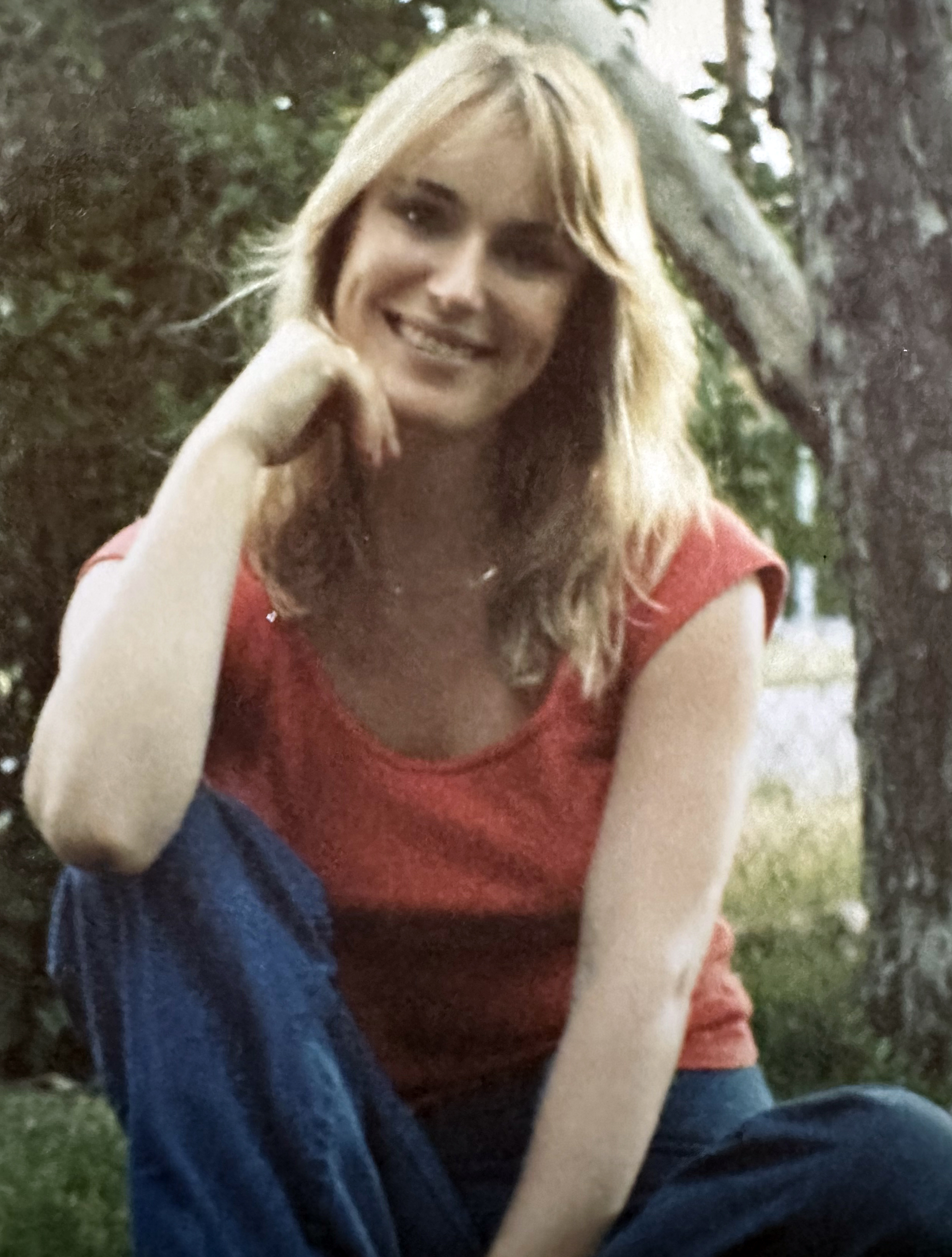

Susan Bowlus circa 1979Courtesy Susan Bowlus

Susan Bowlus circa 1979Courtesy Susan Bowlus

But Bowlus was not acknowledged as a survivor by local authorities, and her quest to learn more about her assault would morph into a nightmare all its own: Over four years, she had so much trouble getting records from the sheriff’s office that it began to feel deliberate: “Why were these people that were supposed to be helping me becoming my adversaries?” she asked me rhetorically. Bowlus “felt that she had been failed and betrayed” by law enforcement, says Jim Hopper, a Harvard psychologist who spoke with her before she filed a lawsuit seeking access to the records.

Citinginsufficient evidence, authorities frequently deny victims of violent crimes access to government resources, including state compensation funds established to help survivors cover the costs of therapy, lost wages, or funerals. That’s according to Jennifer James, a sociologist at the University of California, San Francisco. Officials who administer the funds tend to assume “people are lying” if they don’t have all their records, and so they “weed them out,” James said.

Bowlus, indeed, spent years trying to get her share of the compensation the state legislature promised to each of the Golden State Killer’s living victims. Along the way, she learned she was not alone. There were other potential survivors still out there in need of assistance—and closure.

Bowlus grew up in Northern California and moved to Sacramento to attend Heald Business College, where she studied to be a legal secretary. In her early 20s, she got a secretarial job with a railroad company, where her roommate also worked.

The gig wasn’t her dream—she wanted to become a photographer—but it paid well enough to buy a house in nearby Citrus Heights with a big oak tree in the backyard. It was in the fall of 1979, as she was looking forward to a promotion to railroad engineer, a role very few women held, that the attack took place.

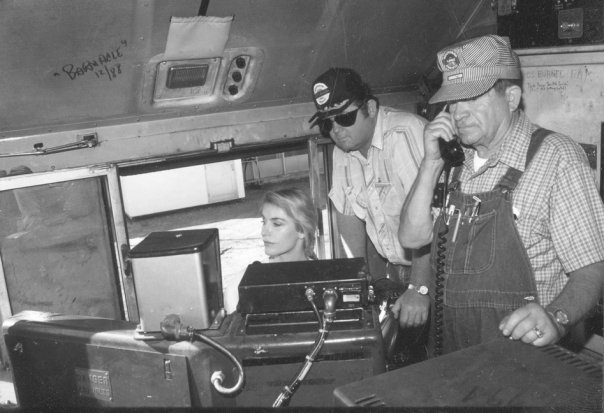

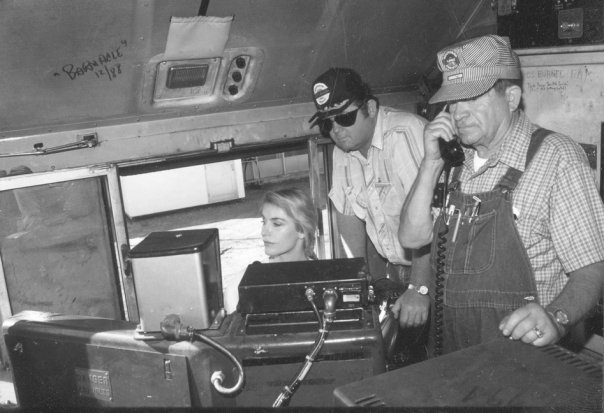

Bowlus worked as a railroad engineer in the early 1980sCourtesy Susan Bowlus

Bowlus worked as a railroad engineer in the early 1980sCourtesy Susan Bowlus

She recalls falling asleep after midnight on September 25 and waking up with a man on top of her. He’d already blindfolded her and proceeded to tie her up. The attack lasted for hours as he moved her from room to room. She prayed for her survival as he started rattling knives in a kitchen drawer. “I was strong, but in dire fear I would not make it out alive,” she told me.

When her attacker finally left, she ran outside for help, pounding on her neighbors’ door. They called the police, and she went to the hospital for a forensic exam. Afterward, she sold her house, relocated to Nevada, and focused on her engineering job at the Southern Pacific Railroad Company. She would eventually move to New York City to pursue her current career as a portrait and fashion photographer.

In the meantime, for decades, she tried to move on from that traumatic night in Citrus Heights. But after hearing from her friend and following DeAngelo’s prosecution, Bowlus couldn’t ignore her insatiable curiosity to find out what had happened to her. “I was always wondering through the years” who did it, she says. She hoped an answer might exist in her crime report, but when she first requested the documents in 2020, the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office said it couldn’t find them. She asked the staff to keep looking.

Joseph DeAngelo, who was dubbed the East Area Rapist, the Golden State Killer, and other nicknames, appears in a Sacramento County courtroom with public defender Diane Howard for his arraignment on multiple murder and rape-related charges in April 2018.Paul Chinn/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty

Joseph DeAngelo, who was dubbed the East Area Rapist, the Golden State Killer, and other nicknames, appears in a Sacramento County courtroom with public defender Diane Howard for his arraignment on multiple murder and rape-related charges in April 2018.Paul Chinn/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty

After DeAngelo’s sentencing, the office finally produced the report, but it was incomplete. Whoever had redacted the page numbers had forgotten one—“page 15 of 24”—which caught Bowlus’ attention, because the office had handed over only 20 pages.

When she inquired further, staff at the sheriff’s records bureau said they’d given her everything except a few pages of medical records, which they’d need a court order to release. Puzzled, she reached out to the district attorney’s office, where an investigator agreed to request the remaining pages on her behalf. “It doesn’t make sense that you can’t get your own medical records,” the investigator, Kevin Papineau, wrote to her in an email. But his request to the sheriff’s office was rejected.

As Bowlus obsessed over her case documents, she started to experience intense anxiety and problems sleeping. Why couldn’t she see her own medical files? Striking out with law enforcement, she turned to other survivors for support. Rose Ireland, who’d been attacked by DeAngelo in Santa Barbara County, told her that state lawmakers had passed a law allowing his victims to apply for up to $10,000 apiece for therapy to help them deal with their trauma—Ireland’s application had been approved. Bowlus, noting the close similarities between her case and the others, decided to try.

This, too, proved more challenging than she’d anticipated. California’s Victim Compensation Board, the agency processing the applications, denied her request, arguing that she was not a crime victim. Bowlus pushed back—she had 20 pages of her crime report, after all—whereupon the board clarified that she was not a victim of the Golden State Killer specifically.

When Bowlus emailed the sheriff’s office to ask about this, Detective Rob Peters wrote back to say there wasn’t enough evidence linking her attack to DeAngelo. “There were very specific things he would say to his victims, things he would have his victims do, as well as things he would take from the residences,” he wrote, and “none of those things were in your report.” Peters suggested that perhaps she’d been assaulted by another serial criminal such as the Woolly rapist, who wore wool gloves during his crimes in the 1970s. But that was impossible—the Woolly rapist was locked up at the time she was attacked.

In fact, there were parallels between Bowlus’ rape and ones DeAngelo committed that conflicted with what Peters had claimed: The Golden State Killer often burglarized other homes in the neighborhood first. His victims tended not to hear him enter, and he usually moved them from room to room and rummaged through their things. All of that happened to her. Her attack had lasted about four hours. “I don’t know any other rapist that would stay in the house that long,” Shelby, the retired detective, told me. Her perpetrator also had repeatedly told her to “shut up,” asked her to get lubricant and masturbate, and instructed her to remain still for at least 15 minutes after he left the premises—all rather unusual habits of DeAngelo, according to court filings in her case. How could the sheriff’s office be so sure her rapist wasn’t DeAngelo?

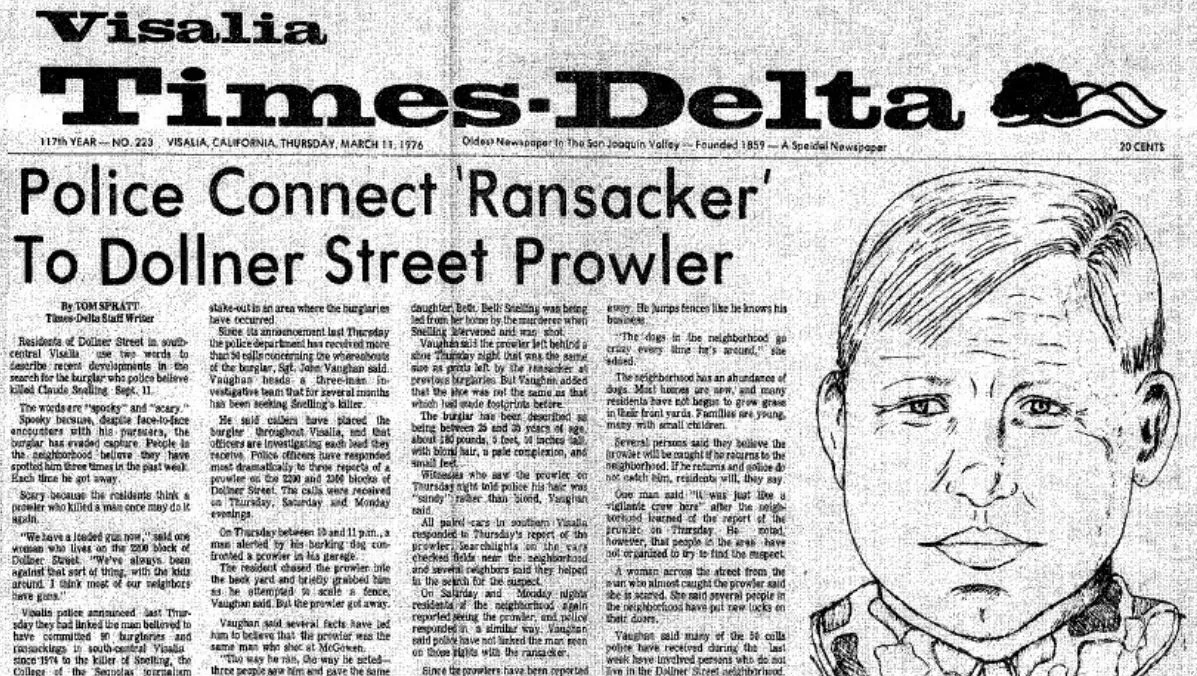

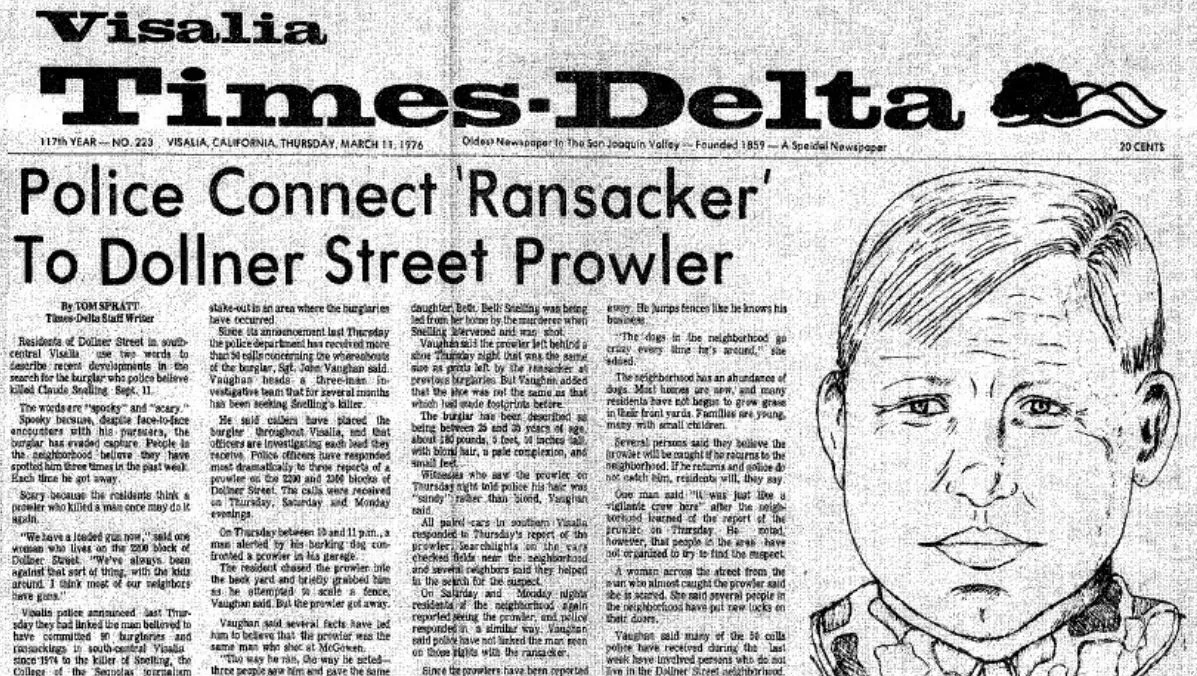

DeAngelo was also identified as the Visalia Ransacker because of the crimes he committed there, including a murder, during the 1970s.Visalia Times-Delta

DeAngelo was also identified as the Visalia Ransacker because of the crimes he committed there, including a murder, during the 1970s.Visalia Times-Delta

When Bowlus posed that question, Peters simply reiterated that her assault did not sound like a typical DeAngelo assault and that he felt confident about his assessment after reviewing 54 pages of her file. This, too, confused her: Hadn’t the records bureau suggested there were only 24 pages?

Frustrated, Bowlus turned to private investigator Tony Reid, an expert on the Golden State Killer who had helped law enforcement search for him and then wrote a book on the subject. Reid had obtained crime reports for other victims while trying to help an incarcerated man he believed was framed for one of DeAngelo’s crimes. Bowlus messaged him on Facebook in 2020, and he’d been intrigued enough to take her case.

Then, a bombshell: In 2022, Reid got a trove of documents from an anonymous source—47 pages of Bowlus’ crime report, or 27 more than she’d already received.

The documents showed there had been footprints outside Bowlus’ house that resembled those of DeAngelo: same size, same type of shoe. Jim Bevins, the lead investigator on the interagency Golden State Killer task force during the 1970s, had investigated her rape and had sent Bowlus’ bedsheets to a forensic lab for analysis. “There is nothing in the available information” that would exclude DeAngelo as a suspect, Reid wrote in a report later submitted in court.

With this evidence, Bowlus hoped she could convince the Victim Compensation Board to approve her therapy funding. Wasn’t it clear or at least probable that she’d been attacked by DeAngelo? The sheriff’s office still didn’t think so, though it stillhadn’t shared her full file with her. And the board continued to deny her application, citing lack of proof.

An undated photo released by the FBI shows ski masks from East Area Rapist cases.FBI/AP

An undated photo released by the FBI shows ski masks from East Area Rapist cases.FBI/AP

California’s Victim Compensation Board, established in the 1960s, was a first of its kind in the nation, though every state now has one. It’s a three-member panel that reimburses people for expenses related to violent crimes, from hospital bills and funeral costs to lost wages and therapy fees. California typically gives victims seven years to apply, but in 2018, state lawmakers enacted a bill extending the deadline for Golden State Killer survivors.

Crime victims nationwide have long complained about the red tape they’ve encountered when applying for compensation funds: There’s a lot of paperwork, and the requirement to submit police reports can be disqualifying for some people. In a 2022 survey, the victims advocacy group Alliance for Safety and Justice found that 96 percent of violent crime victims never saw a dime, and three-quarters received no mental health support.

In California and nationally, about half of violent crimes aren’t even reported to police, the same survey found, often because the victims don’t believe law enforcement will help them. In another 2022 report, the nonprofit Prosecutors Alliance of California found that roughly 70 percent of the 700 crime survivors surveyed didn’t know why they had been denied compensation.

FBI Special Agent Marcus Knutson (left) and Sacramento County Sheriff’s Deputy Paige Kneeland look for evidence at the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office.FBI/AP

FBI Special Agent Marcus Knutson (left) and Sacramento County Sheriff’s Deputy Paige Kneeland look for evidence at the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office.FBI/AP

As Bowlus was fighting for access to her records, the California Legislature passed a law to compensate people forcibly sterilized while serving time in state prison years before. But the Victim Compensation Board denied more than 300 of the 500-plus applications it received, most often for lack of documentation. Journalists at KQED and the Nation identified multiple cases in which former prisoners with valid claims were rejected. “Many people experienced trauma from applying,” said James, the UCSF professor, who helped some of them apply. “It feels like as a state, as a society, we’ve prioritized bureaucracy—needing to weed out fraud and someone taking advantage of the system—over making sure that everyone who needs care or resources is able to access services.”

After the board rejected Bowlus’ first application and appeals, she asked it to request her complete 54-page file from the sheriff’s office—a California court had previously ruled that the board is obligated “to obtain full crime reports from law enforcement agencies…through its subpoena power if necessary.” The board refused—so Bowlus filed a lawsuit. Under legal pressure, the board issued a subpoena and the sheriff’s office finally handed over 24 pages to Bowlus, and ultimately, after some urging, the additional 23 pages that private investigator Reid had obtained.

But seven pages were still missing. Bowlus and Reid suspected they contained the lab results for the semen-stained sheets that were sent for testing, which might have identified the perpetrator. “Of all the things that could go missing from a case file,” Reid told me, “this would be the last. This would have been essential information for any prosecution.”

The DA’s office also told Bowlus that it didn’t have the semen analysis from her sheets. But the lack of transparency Bowlus faced throughout her quest left her highly skeptical. “It was so traumatizing to be gaslit,” she told me. She and her supporters began to wonder whether local officials were hiding something. “Somebody was not producing all the documents,” says her attorney, Patrick Dwyer. “And the question was, why?”

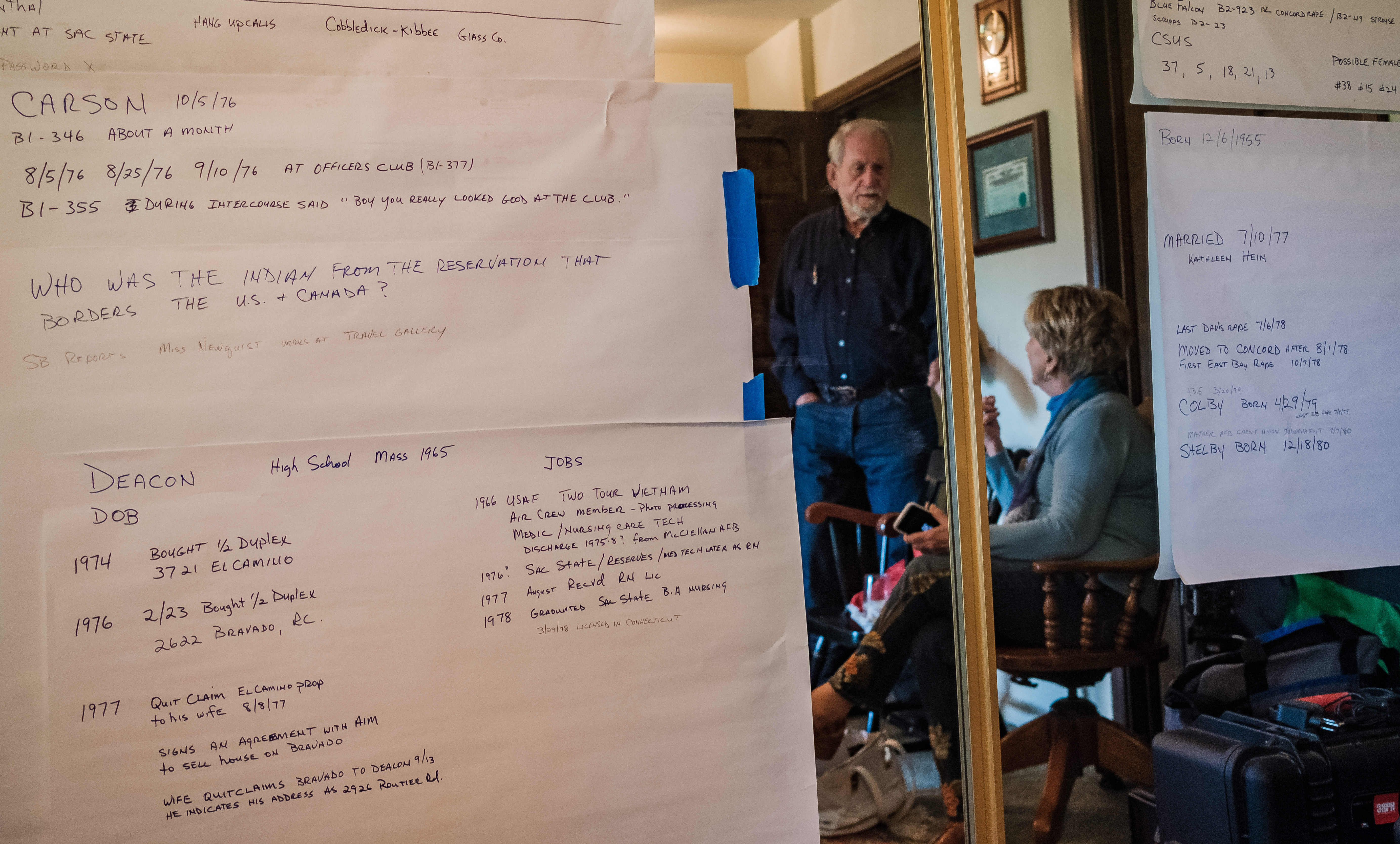

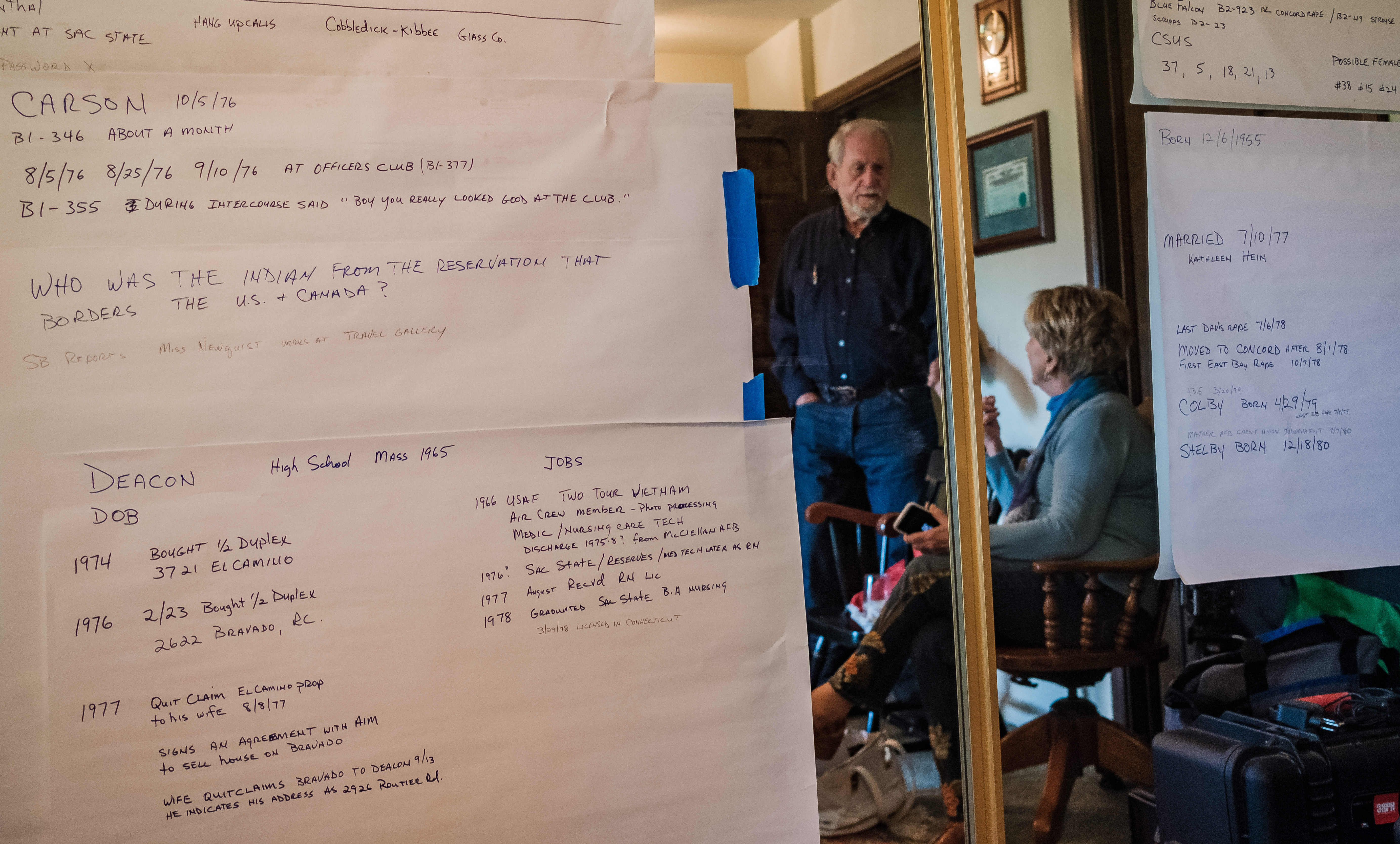

Carol Daly and Richard Shelby were two of the original detectives assigned to the East Area Rapist (Golden State Killer) case. On the mirror are notes taken by Russ Oase, a friend of Shelby’s and former federal officer who pursued the case on his own time.Nick Otto/Washington Post/Getty

Carol Daly and Richard Shelby were two of the original detectives assigned to the East Area Rapist (Golden State Killer) case. On the mirror are notes taken by Russ Oase, a friend of Shelby’s and former federal officer who pursued the case on his own time.Nick Otto/Washington Post/Getty

That question became harder to ignore after Reid obtained yet another record: an internal police memo from March 1979 that cast even more doubt on the sheriff’s office’s claims. Peters, the detective, had told Bowlus that DeAngelo could not have been her attacker because he’d already left Sacramento by 1979 and moved elsewhere in California. But in this memo, issued a few months before Bowlus was raped, a police officer on the East Area Rapist Interagency Task Force informed his team that he believed the Golden State Killer had tried to rape someone else in Sacramento County that week. The officer wrote that the sheriff’s office wanted to hide this new attack from the public “so that the press will not over-react” and cause more panic.

This came as a shock for Bowlus. Could the sheriff’s office now be brushing her off, she wondered, because her rape had happened at a time when county officials were leading the public to believe—despite potential evidence to the contrary—that the Golden State Killer was no longer located there?

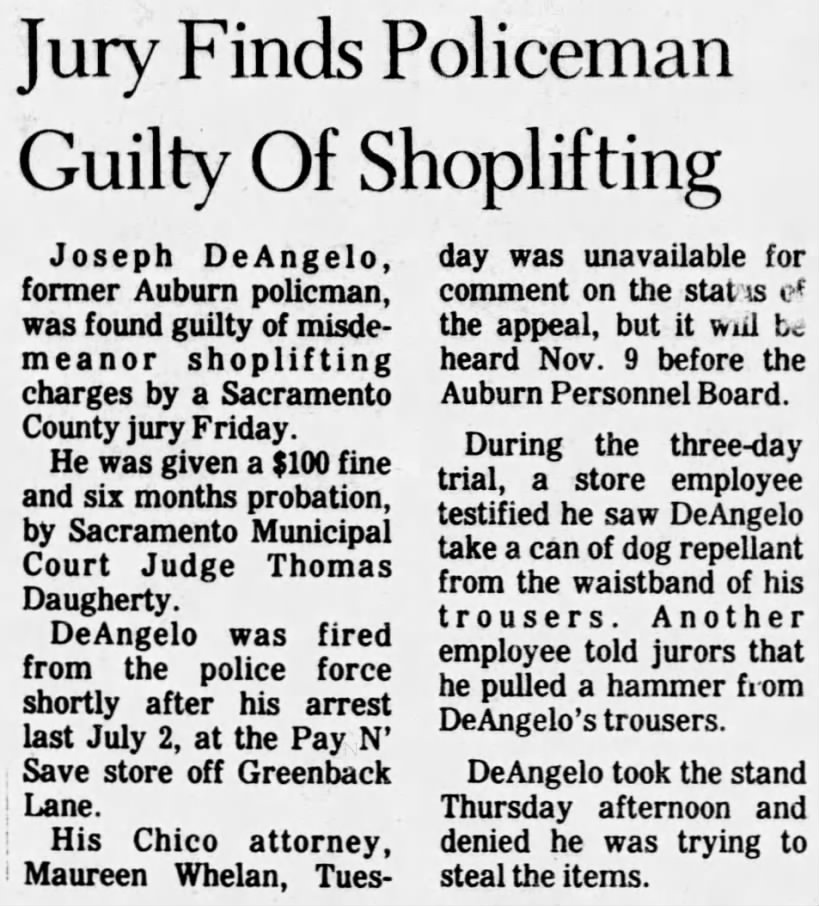

Even more upsetting: The memo’s author had predicted the killer would strike again on a Tuesday, as was his habit. That was the day of the week Bowlus was raped. (DeAngelo was arrested for shoplifting a few miles from Bowlus’ house in July 1979. He was suspended from his job at the Auburn Police Department that August; she was raped in September.) “They lied to the public, knowing that he’s still attacking,” she thought. “The community was not warned.”

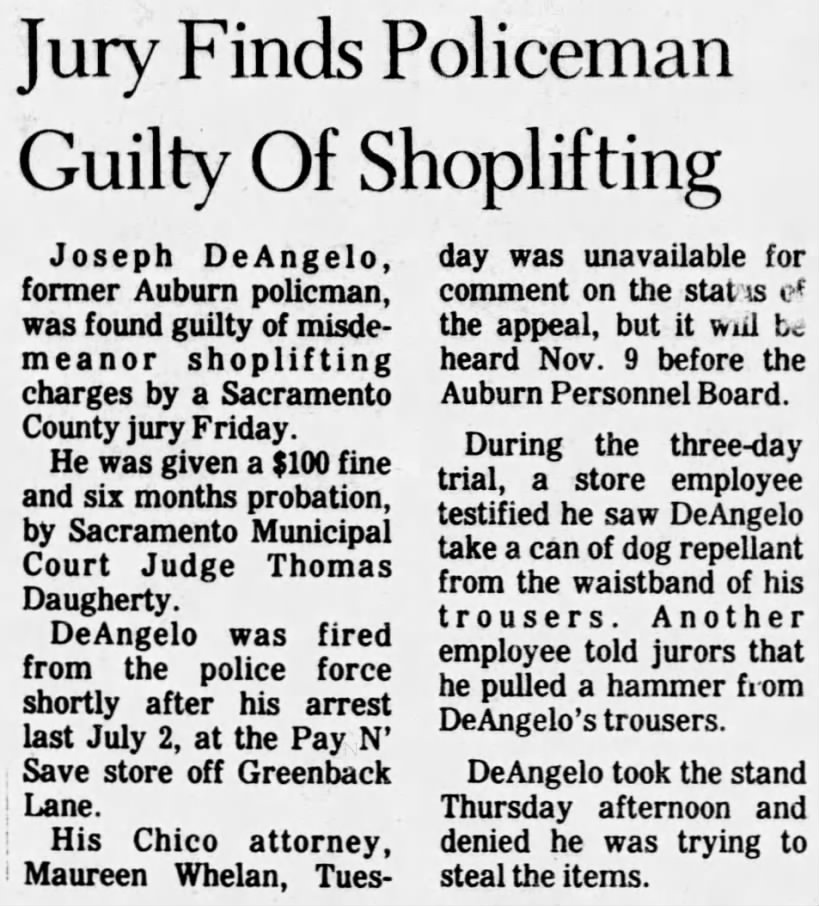

An article from the Auburn Record notes DeAngelo’s shoplifting conviction.Auburn Record

An article from the Auburn Record notes DeAngelo’s shoplifting conviction.Auburn Record

The internal memo clearly states that Sacramento authorities intended to concealfrom the public the Golden State Killer’s likely whereabouts in 1979. A year earlier, the Bay Area Journal reported that the sheriff’s office had previously asked journalists to “sit on” the story a while, so as not to jeopardize the Golden State Killer investigation—as those reporters held off on publishing, more women were raped. Journalists “are cooperating very well,” Bevins, the investigator who later looked into Bowlus’ case, told the Journal.

I found no evidence to support Bowlus’ suspicion that the sheriff’s office was trying to cover up something related to her case—though that doesn’t mean it wasn’t. (The office did not respond to my requests for comment and rejected my public records request. The district attorney’s office also declined to comment.)

Shelby, the former detective, who retired in 1993, told me that he doubted the sheriff’s office was conspiring to deny her the records. More likely, he said, its personnel were stretched thin and didn’t see much point in spending time on her case—and frankly didn’t care because DeAngelo is in prison. “In their mind, it’s over and done,” he said. “They’re thinking, ‘It’s not him, and we don’t even care if it is because he’s already arrested; we’re not gonna spin our wheels.’”In the meantime, Bowlus was denied the help she sought. “It’s incomprehensible why they’d spend more than four years torturing an identified, known, agreed rape victim,” says Kristen Reid, investigator Tony Reid’s spouse and business partner, “instead of spending five minutes to resolve an easy question of forensics.”

Or simply asking the Golden State Killer, who had no incentive to lie. Earlier this month, Tony Reid got his hands on the minutes from DeAngelo’s 2020 sentencing. Prosecutors had made an unusual deal with the serial killer: In exchange for him pleading guilty to 13 murders and 13 kidnappings and admitting to 161 other uncharged crimes, they agreed to never press any more charges, even if he admitted to other crimes later.

This past September, the Victim Compensation Board finallyapproved Bowlus’ application. After half a decade advocating for herself, she received state funding to cover the cost of therapy. A judge also ordered the state to pay $83,000 to cover her attorney’s fees.

The board has, by now, granted money to 29 of the killer’s 33 survivors who applied. But at least a couple of others didn’t bother submitting applications because they’d already been disappointed by how police treated them and couldn’t stomach another bad interaction.

Liz Silva was 12 years old when she was abducted and raped by a cop she now believes was DeAngelo, based on his appearance and the fact that her stepdad worked in the same town as DeAngelo for a while. She says the Sacramento County DA’s office did not invite her to DeAngelo’s 2020 sentencing hearing because she lacked enough evidence—the snub left her feeling “totally dismissed.”

DeAngelo joined the Exeter Police Department in 1973, around the time 12-year-old Liz Silva was raped by a police officer.Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office

DeAngelo joined the Exeter Police Department in 1973, around the time 12-year-old Liz Silva was raped by a police officer.Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office

I also spoke with Karen Burns, who was raped in a Sacramento-area home invasion in 1979, shortly after Bowlus’ attack. She struggled to obtain all her records from a police department after DeAngelo’s arrest and didn’t apply for victim compensation, she says, after she heard how much trouble Bowlus was having: “I started getting everything together,” all the paperwork, “but I didn’t have it in me to finish and get disappointed again.”

Hopper, the Harvard psychologist, told me police are sometimes insensitive with survivors because of their training: “It can be a job where you’re overwhelmed, you’re dealing with things nobody else wants to deal with, you’ve got too many cases, and criminals who are lying to you all the time. The interviewing methods you learn can be focused on trying to break down the criminals and get them to confess, and those can become deeply ingrained habits, and now you’ve got a rape victim sitting across from you.”

But when cops treat survivors with suspicion and question their honesty, he says, it can cause “betrayal trauma,” wherein victims feel hurt by an institution that was supposed to help them.

Every case is unique, but the experts I spoke with said the roadblocks Bowlus faced are a nationwide problem. “Most crime victims have encountered similar challenges in getting any kind of information from law enforcement,” says Tinisch Hollins, executive director of the advocacy group Californians for Safety and Justice. That ranges from follow-up and general information about their case to the documents and evidence the victims need to show to secure compensation.

According to attorney David Snyder, executive director of the nonprofit First Amendment Coalition, California’s public records law generally allows police to withhold arrest reports indefinitely. “A lot of people assume that when an investigation is over, you can get the records. That’s not the case,” says Snyder, who has done legal work for Mother Jones in the past, and there’s little oversight to ensure that police are handing over even the documents they are required to share.

Californians for Safety and Justice is pushing a bill introduced by San Diego Assemblywoman LaeShae Sharp-Collins that would make it easier to apply for compensation without a police report—instead, survivors could provide records from a counselor or social worker showing they were harmed. The state “is failing to help many victims of violent crime,” she said in a statement accompanying the bill.

“People for many reasons are afraid of police, or they’re afraid of retaliation by the perpetrator, or they are so traumatized they don’t want to go through a lengthy court proceeding, but if they don’t file a police report, they can’t access services,” says Alicia Boccellari, a San Francisco Bay Area psychologist who works with survivors. In 2001, she created a first-of-its-kind trauma recovery center at UCSF to provide free services ranging from victim support groups to home visits and assistance with compensation applications. Now there are trauma recovery centers statewide, and in other states, too, though some have had their funding cut by the Trump administration.

Susan Bowlus in the Citrus Heights neighborhood where she was attacked.Sam Van Pykeren

Susan Bowlus in the Citrus Heights neighborhood where she was attacked.Sam Van Pykeren

It is too late for Bowlus to benefit from these reforms. In April, I met her outside her old house in Citrus Heights, where a family now lives. She admired the big oak tree in the backyard, always her favorite part of the property, and said she was relieved that it had survived as long as she had. As we walked around the neighborhood, she told me about the therapy she’d started and the coping tools she was learning.

She had been practicing summoning an image of her favorite place—Lake Tahoe, where she loves to spend afternoons with a book and a sandwich. She thinks often of Sacramento Superior Court Judge Jennifer Rockwell, who took her side and helped her get therapy.

Bowlus may never see all of her records. After so many years obsessing over how to get them, she is trying to move on. But this, too, is harder than she’d imagined.

“It’s an age-old story, the fight for truth and justice,” she says. “And is it worth it?”

From Mother Jones via this RSS feed

Muhammad Zakariya Ayyoub al-Matouq dropped from 9 to 6 kilograms and struggles to survive in a tent in Gaza City, where milk, food, and other basic necessities are lacking.Omar Ashtawy/APA/ZUMA

Muhammad Zakariya Ayyoub al-Matouq dropped from 9 to 6 kilograms and struggles to survive in a tent in Gaza City, where milk, food, and other basic necessities are lacking.Omar Ashtawy/APA/ZUMA Injured people and bodies were brought to Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City after Israeli forces opened fire on civilians who were waiting for humanitarian aid in north Gaza on Sunday.Omar Ashtawy/APA/ZUMA

Injured people and bodies were brought to Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City after Israeli forces opened fire on civilians who were waiting for humanitarian aid in north Gaza on Sunday.Omar Ashtawy/APA/ZUMA Abdul Jawad Al-Ghalban, 14, died from severe malnutrition at Nasser Medical Hospital in Khan Younis. He is pictured on Tuesday.Moaz Abu Taha/APA/ZUMA

Abdul Jawad Al-Ghalban, 14, died from severe malnutrition at Nasser Medical Hospital in Khan Younis. He is pictured on Tuesday.Moaz Abu Taha/APA/ZUMA A charity organization distributes hot meals to Palestinians in Gaza City on Thursday.Omar Ashtawy/APA/ZUMA

A charity organization distributes hot meals to Palestinians in Gaza City on Thursday.Omar Ashtawy/APA/ZUMA Kara Ayers, associate director of the University of Cincinnati Center for Excellence in Developmental DisabilitiesCourtesy of Kara Ayers

Kara Ayers, associate director of the University of Cincinnati Center for Excellence in Developmental DisabilitiesCourtesy of Kara Ayers “Space law has taught me that there are lots of avenues for a special interest,” says AJ Link.Courtesy of AJ Link

“Space law has taught me that there are lots of avenues for a special interest,” says AJ Link.Courtesy of AJ Link Marisa Hamamoto’s Infinite Flow Dance company includes both disabled and non-disabled dancers.Samantha Tokita

Marisa Hamamoto’s Infinite Flow Dance company includes both disabled and non-disabled dancers.Samantha Tokita Susan Bowlus circa 1979Courtesy Susan Bowlus

Susan Bowlus circa 1979Courtesy Susan Bowlus Bowlus worked as a railroad engineer in the early 1980sCourtesy Susan Bowlus

Bowlus worked as a railroad engineer in the early 1980sCourtesy Susan Bowlus Joseph DeAngelo, who was dubbed the East Area Rapist, the Golden State Killer, and other nicknames, appears in a Sacramento County courtroom with public defender Diane Howard for his arraignment on multiple murder and rape-related charges in April 2018.Paul Chinn/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty

Joseph DeAngelo, who was dubbed the East Area Rapist, the Golden State Killer, and other nicknames, appears in a Sacramento County courtroom with public defender Diane Howard for his arraignment on multiple murder and rape-related charges in April 2018.Paul Chinn/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty DeAngelo was also identified as the Visalia Ransacker because of the crimes he committed there, including a murder, during the 1970s.Visalia Times-Delta

DeAngelo was also identified as the Visalia Ransacker because of the crimes he committed there, including a murder, during the 1970s.Visalia Times-Delta An undated photo released by the FBI shows ski masks from East Area Rapist cases.FBI/AP

An undated photo released by the FBI shows ski masks from East Area Rapist cases.FBI/AP FBI Special Agent Marcus Knutson (left) and Sacramento County Sheriff’s Deputy Paige Kneeland look for evidence at the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office.FBI/AP

FBI Special Agent Marcus Knutson (left) and Sacramento County Sheriff’s Deputy Paige Kneeland look for evidence at the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office.FBI/AP Carol Daly and Richard Shelby were two of the original detectives assigned to the East Area Rapist (Golden State Killer) case. On the mirror are notes taken by Russ Oase, a friend of Shelby’s and former federal officer who pursued the case on his own time.Nick Otto/Washington Post/Getty

Carol Daly and Richard Shelby were two of the original detectives assigned to the East Area Rapist (Golden State Killer) case. On the mirror are notes taken by Russ Oase, a friend of Shelby’s and former federal officer who pursued the case on his own time.Nick Otto/Washington Post/Getty An article from the Auburn Record notes DeAngelo’s shoplifting conviction.Auburn Record

An article from the Auburn Record notes DeAngelo’s shoplifting conviction.Auburn Record DeAngelo joined the Exeter Police Department in 1973, around the time 12-year-old Liz Silva was raped by a police officer.Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office

DeAngelo joined the Exeter Police Department in 1973, around the time 12-year-old Liz Silva was raped by a police officer.Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office Susan Bowlus in the Citrus Heights neighborhood where she was attacked.Sam Van Pykeren

Susan Bowlus in the Citrus Heights neighborhood where she was attacked.Sam Van Pykeren

Chantal Jahchan; Rebecca Noble/Getty; Getty

Chantal Jahchan; Rebecca Noble/Getty; Getty Wearing mosquito netting, Florida State Sen. Shevrin Jones, State Rep. Michele K. Rayner and Rep. Anna V. Eskamani, PhD, are denied entry along with fellow representatives into Alligator Alcatraz in Collier County, Florida.Al Diaz/Miami Herald/Tribune News Service/Getty

Wearing mosquito netting, Florida State Sen. Shevrin Jones, State Rep. Michele K. Rayner and Rep. Anna V. Eskamani, PhD, are denied entry along with fellow representatives into Alligator Alcatraz in Collier County, Florida.Al Diaz/Miami Herald/Tribune News Service/Getty US President President Donald Trump tours a migrant detention center, dubbed “Alligator Alcatraz,” located at the site of the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport in Ochopee, Florida on July 1, 2025. Andrew Caballero/AFP/Getty

US President President Donald Trump tours a migrant detention center, dubbed “Alligator Alcatraz,” located at the site of the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport in Ochopee, Florida on July 1, 2025. Andrew Caballero/AFP/Getty Shawn Ryan has conducted interviews with RFK Jr., Donald Trump, Tulsi Gabbard, and JD Vance, among other MAGA celebrities.Shawn Ryan Show/Youtube

Shawn Ryan has conducted interviews with RFK Jr., Donald Trump, Tulsi Gabbard, and JD Vance, among other MAGA celebrities.Shawn Ryan Show/Youtube ICE agents arrest noncitizens inside 26 Federal Plaza in New York on July 1.Cristina Matuozzi/Sipa USA/AP

ICE agents arrest noncitizens inside 26 Federal Plaza in New York on July 1.Cristina Matuozzi/Sipa USA/AP Federal agents walk around at the immigration court at the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in New York in June.Yuki Iwamura/AP

Federal agents walk around at the immigration court at the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in New York in June.Yuki Iwamura/AP President Donald Trump, with Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, is welcomed by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis. Daniel Torok/White House/Planet Pix/Zuma

President Donald Trump, with Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, is welcomed by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis. Daniel Torok/White House/Planet Pix/Zuma