Last fall, retired Judge Karen Radius leaned on her cane as she walked me toward the girls’ housing unit at Hawaii’s only youth prison, remembering the moment three years ago when she’d learned no more girls were living there.

For Radius, a disarmingly matter-of-fact 76-year-old who’d spent much of her career trying to keep teens out of detention, the empty housing unit came as the best kind of news. “These aren’t fucking evil kids who commit bad crimes,” she said as we passed a couple of incarcerated boys studying in classrooms.

The absence of girls at the prison was the rare positive criminal justice story to get national attention. Politicians and activists mused whether Hawaii—a pioneer for women’s and girls’ rights as the first state to legalize abortion and ratify the Equal Rights Amendment—might also have found a way to stop locking them up. “Another world is possible,” New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez posted after learning of the news. “Now do the boys,” one of her followers added.

Ending prison for teens might seem like a pipe dream in the age of Donald Trump. But when it comes to girls, who are less likely than boys to commit violence, this fantasy could be closer to reality than you’d think. Maine, Vermont, New York City, and parts of the San Francisco Bay Area also have seen long stretches without a single girl in long-term incarceration. In California, stopping girls’ imprisonment altogether is now “well within reach for the state,” according to the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice, which works with jurisdictions across the country to get kids out of detention. “It’s hard for a lot of communities, let alone government leaders, to imagine that zero is achievable. We know that it is,” says Hannah Green, who helped lead Vera’s Ending Girls’ Incarceration Initiative until last year.

What these places have in common is a radical shift in thinking about how to keep kids out of prison. Juvenile diversion programs have existed for decades, often in the form of special courts that order children to go through drug rehab or counseling or anger management programs as alternatives to incarceration. But those courts tend to follow a “medical model,” in which adult experts like judges diagnose the individual flaws that made a child act out—addiction, maybe, or too much aggression—and propose a solution. Kids who don’t comply are often locked up.

Judge Karen Radius in Girls Court in Honolulu.Elyse Butler

Judge Karen Radius in Girls Court in Honolulu.Elyse Butler

Radius and other reformers instead champion the “advocacy model,” which views girls as experts on their own lives and what they need to thrive. The key, says Lindsay Rosenthal, the founding director of Vera’s decarceration initiative, is “not just assuming” what’s driving girls’ arrests, but asking them which resources they need to stay out of detention—and “really listening” to their answers.

From Hawaii to New York, the advocacy model is keeping girls out of prison. It’s saving money. It’s improving public safety. All of which raises the question: What if we expanded it to other people, too?

In a decade of reporting on the criminal justice system, I haven’t encountered much reason for optimism. Three years ago, after wrapping up an investigation about Oklahoma moms who were imprisoned because they and their children were abused by violent boyfriends (yes, you read that right), I felt desperate for some better news. Who was improving the system? Hawaii had just made headlines for its girl-free prison. A bit of digging pointed to the Girls Court, a groundbreaking program Radius created two decades ago. I booked a flight.

The court grew out of an observation that had irked Radius during her early days as a judge. She was raised on the South Side of Chicago by working-class parents. After graduating from George Washington University Law School as one of few women in her class, she decided to leave DC, where, as she put it to me over coffee, “you have to carry someone else’s briefcase for 10 years before you become anything.” She moved to Oahu in 1974 in her mid-20s and became a Legal Aid defense lawyer for low-income kids. In the beginning, her caseload was almost entirely boys. But after she became a judge in 1993, she noticed the gender balance shifting; half the kids who came before her bench were girls. “I’d go back to the office and say, ‘Is anybody else seeing this, or am I just the girl magnet?’” she recalled.

Girls Court is “Flipping that script from thinking about where girls have failed to thinking about where systems have failed girls.”

It wasn’t just her: From 1990 to 1999, the number of delinquent girls detained in the United States grew 50 percent, compared with a 4 percent increase for boys. Youth crime had been rising since the ’80s, and though politicians famously fixated on male teen “superpredators,” their tough-on-crime mentality targeted girls too, with zero-tolerance policies that led to more girls being arrested for fights. The media latched on: Newsweek ran a piece in 1993 titled “Girls Will Be Girls” about teens with guns and “razor blades in their mouths,” while Oprah and Larry King decried the scourge of girl gangs.

Then, in what seemed like a remarkable change starting around 2000, youth incarceration began to drop by more than half. But the proportion of girls in detention, especially girls of color, continued to climb.

And as girls took up more beds in youth lockups, they faced a legal system that had not been built for them: Three-quarters of all juvenile justice programs served only or primarily boys—just 2 percent served only girls. People assumed both genders committed violence for similar reasons, and that the existing punishment structure for boys would work for girls, too.

But girls had different needs. They were less likely than boys to be arrested for violence, and more likely to be arrested for running away, skipping school, and other so-called “status offenses” that were only deemed illegal because of the offender’s age. These transgressions often stemmed from prior trauma. Nationally, according to a 2010 study, 35 percent of incarcerated girls reported previous sexual abuse, compared with 8 percent of boys. Girls in the justice system were also twice as likely as boys to report physical abuse and past suicide attempts.

Courts had a long history of trying to protect girls by locking them up. “There was thinking across the nation that sometimes you have to put kids in detention to save them from themselves,” says Robert Browning, a senior judge who later helped Radius with her reforms. “‘If she’s in jail, at least she’s not gonna run. She won’t be on the street using ice [methamphetamine] with God knows who.’”

That kind of paternalism had deep roots. In the early 1900s, wayward immigrant and working-class girls were sent to “reformatories” charged with shaping them into acceptable wives and mothers. Some of the earliest status offense laws, which also governed things like missing curfew or disobeying parents, applied until age 16 for boys but 18 for girls. Girls were policed for their sexuality, as well. In the 1920s, some were even given gynecological exams at the time of arrest and incarcerated if their hymens were torn.

The legacy of these approaches didn’t sit well with Radius, and she grew frustrated by her limited options as a judge. If she wanted to divert girls from incarceration, she could choose between boy-centric boot camps or anger-management classes, but neither was designed with girls’ needs in mind. In 2003, she went to her boss, Frances Wong, and made a bold request.

“Let me do a Girls Court,” she asked.

“What’s that?” Wong replied.

“I have no idea,” Radius said, “but we gotta do something different.”

The seeds of the “advocacy model” were planted during the civil rights movement in the 1960s, when a group of American psychologists grew tired of their profession’s obsession with blaming individuals for their own mental illnesses. President John Kennedy had recently signed a law to remove people from long-term mental institutions, following press coverage of their horrendous conditions. As protests raged for racial equality and against the Vietnam War, psychologists at a 1965 conference in Swampscott, Massachusetts, proposed focusing not just on an individual’s thoughts and feelings, but also on broader structures and settings: How did poverty, racism, sexism, and other circumstances and relationships affect people’s health and behavior? In the field of “community psychology,” as their discipline would be known, systems, not individuals, were the target of change.

These ideas began to seep into juvenile justice. In 1976, court officials in Ingham County, Michigan, were frustrated at the high cost of incarcerating kids. Alongside Michigan State University faculty and grad students, they launched the Adolescent Diversion Project, a program that took a page from community psychology and tried to reduce teen crime by improving support for boys: strengthening their ties to family, connecting them with neighborhood resources, and keeping them away from negative influences at juvenile hall. Ten years later, MSU researchers launched the Community Advocacy Project, which paired women who’d survived intimate partner violence with community “advocates,” often students, who would ask them about their goals and connect them with resources.

Judge Radius hadn’t heard about advocacy models when she decided to start a court just for girls. But it seemed clear to her that many girls were shaped by conditions beyond their control. She’d learned about a groundbreaking study by Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that found that traumatic incidents during early childhood could have lasting negative impacts on a person’s physical, mental, emotional, and behavioral development. Radius’ most important job as a judge, she now felt, was not to determine whether a girl had committed a crime—but rather to figure out what that girl needed to improve her situation.

So she got to work creating Girls Court. Launched in 2004 with a federal grant, it was one of the first courts in the United States to “specialize in solving girls’ problems, as opposed to having them be afterthoughts,” says Meda Chesney-Lind, a nationally renowned criminologist based in Hawaii.

Most of the girls in Radius’ program had a history of sexual abuse, running away, suicide attempts, or drug use; they were either on probation for crimes or under court supervision for repeat status offenses. The court paired each with a female probation officer, who, like the community advocates in Michigan, would try to figure out what resources they needed and what was pushing them to break rules, be it peer relationships, school, medical problems, or family conflict. “Flipping that script from thinking about where girls have failed,” says the Vera Institute’s Green, “to thinking about where systems have failed girls.”

Probation Officer Tia Ikeno and Judge Dyan Medeiros of Girls Court at the Kapolei Courthouse on Oahu, Hawaii.Elyse Butler

Probation Officer Tia Ikeno and Judge Dyan Medeiros of Girls Court at the Kapolei Courthouse on Oahu, Hawaii.Elyse Butler

I wanted to see what flipping the script looked like in practice, so I tagged along with Oahu probation officer Tia Ikeno and her former client Cherish Kapika, 24, who’d graduated from Girls Court several years earlier. Ikeno was picking up Kapika from her new job at the Bank of Hawaii—they’re still in touch regularly. Kapika grinned as she got into the truck: The bank, she announced proudly, had offered to pay for her college tuition. “Tia is gonna be expecting a whole lot of calls now,” she told me through giggles. “She’s gonna be my private—”

“Don’t look at me to be a tutor. I’m not a tutor,” Ikeno said, laughing too.

They had an easy rapport, but it wasn’t always that way. Kapika entered Girls Court in high school after getting in trouble for status offenses, especially running away. She lived on Oahu’s North Shore with her aunt and uncle after her parents, who struggled with addiction, gave up custody when she was a toddler. She wanted to smoke weed and get tattoos and live independently, and she didn’t appreciate Ikeno checking on her. She “was on my butt constantly,” Kapika told me. “I couldn’t stand her.”

Unlike regular juvenile courts where probation officers might work with dozens of teens at once, Girls Court paired Ikeno with just a handful of girls, giving her more time with each. Talking with Kapika every day, Ikeno learned that the teen had a hard time trusting people. Kapika had been neglected before ending up with her aunt and her often taciturn uncle. It was hard for her to focus in school. Ikeno paired her with a therapist, who determined that Kapika’s cognitive functioning was affected not only by childhood trauma but also by fetal alcohol exposure.

Kapika wanted to go to an alternative school her senior year, so the court helped her transfer. Soon she discovered she enjoyed math and coding, and Ikeno helped her get an internship focused on computer games. Kapika also loved the beach, so they signed her up for surfing lessons with a program called Surfrider Spirit Sessions, which specializes in mentorship and experiential education for at-risk youth. The therapist worked with Kapika’s family too, including her uncle; it turned out he’d experienced childhood trauma as well. Slowly he started opening up to Kapika, telling her he cared about her. “She’d never heard him say things like that,” Ikeno said. “With Girls Court, it wasn’t just the girl,” said Kapika’s aunt, Iwalani Sabarre-Kapika. “It was, ‘How do we support the family?’”

Once a month, Kapika went to the courthouse, where a judge asked her what she needed. “I just want them to talk with me,” Judge Dyan Medeiros, the court’s current judge, told me. “It’s important to hear what they have to say. I want them to figure out what they want for their lives, and we help them try to get there.” For Kapika the experience was transformative. She teared up telling me about it. Before, “I never had anybody listen to my side,” she said.

Since 2004, more than a dozen jurisdictions have launched girls courts of their own. They take different forms, but all of them focus on listening to girls and addressing their trauma. A 2007 study by Chesney-Lind found that girls who participated in Hawaii’s court were arrested 79 percent less often than before and were much less likely than other delinquent girls to end up at the state’s youth prison.

As Kapika went through the court, she stopped running away as much and grew closer to Ikeno. “I was one to not trust anyone,” she told me. Now “she’s my emotional support.” After picking Kapika up from work, Ikeno recommended a computer that might help Kapika at college and urged her to put her paycheck into a savings account. Then, as the sun went down, she gave Kapika a ride home.

Despite success stories like Kapika’s, Radius’ Girls Court still has faced criticism from reformers. By checking in with the girls several times a week, probation officers have plenty of opportunities to catch the kids slipping up. And when they do, the court often turns to one of its main tools, a building called Detention Home where kids are sent for short-term stays—days or weeks. Kapika went there and to another shelter about 30 times during her years with the court, whenever she was caught running away. “If it’s a wake-up call—forget sex, drugs, and rock and roll, you’re gonna sit and think for two days,” Radius explains. “In my mind that’s a lot different than ‘You’re gonna stay there a month or two.’”

Kapika said she didn’t mind the arrangement; it gave her space to think. “It was a short break from the real world, where all the issues were,” she told me. But Green at the Vera Institute warns that even short stints of incarceration can cause further trauma. “How can we make sure these resources are available,” she says, “without the threat of detention?”

Turns out, such a system does exist, just a few miles from where I live.

The San Francisco Bay Area is home to a program that’s “the best model in the country” for ending girls’ incarceration, says Shabnam Javdani, a New York University researcher who studies advocacy models. It’s run by the nonprofit Young Women’s Freedom Center, and part of what makes it so effective, Javdani says, is that it’s led by girls and young women who’ve been through the system themselves. More than half the center’s staff are younger than 25, and most have a history of incarceration or living or working on the streets. Last summer, I asked executive director Julia Arroyo for a tour.

Born in San Francisco in 1985, Arroyo entered foster care when she was around 4 and wound up with a family in Milwaukee. Her older brother lived with her there, and she idolized him, dressing in his flannel shirts and baggy pants. After he was sent to a youth detention center, Arroyo was devastated. She ran away when she was 13, hopping a Greyhound bus back to Oakland, where she lived on the streets. Within about a year she was caught shoplifting and booked into juvenile hall. “I was very little, about 85 pounds,” she recalls, with a “miniskirt on and high-heeled shoes. And they were like, ‘Where did this girl come from?’”

Lateefah Simon, 32, executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, and is in her office in San Francisco.Liz Hafalia/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty

Lateefah Simon, 32, executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, and is in her office in San Francisco.Liz Hafalia/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty

One day a woman named Lateefah Simon arrived at the detention center to lead a program. Simon was a young mother in her early 20s running a nonprofit, which later became the Young Women’s Freedom Center, that started in 1993 during the AIDS crisis. Young women and girls in San Francisco’s drug and sex trade—many of them teens of color who’d served time—were paid twice the minimum wage to provide HIV information and supplies to young people on the streets. Eventually the center broadened its focus to keeping them safe not just from infection, but from violence and incarceration.

Simon would later work with Kamala Harris while the future vice president was serving as San Francisco’s district attorney; last year, Harris invited Simon to speak at the Democratic National Convention, months before Simon won her current seat in Congress.

When Simon met Arroyo at the juvenile hall around 1999, she shared her own story of living in housing projects and being on juvenile probation, and she seemed genuinely interested in hearing about Arroyo’s past. It was “a lot of raw talk, like, ‘What’s your plan?’” Arroyo told me. “Everybody else was just telling me what they’re prescribing for me.”

Once Arroyo was released, teens from the center invited her back to their San Francisco headquarters for free food. There, Arroyo was paired with another young woman with similar experiences who would connect her with services. Eventually, Arroyo found an apartment and started working with the center. “We’re trying to empower folks to understand what’s happening in your situation, where do you have decision-making power,” she tells me. “The idea here is never to tell someone, ‘Don’t do that,’ but to make their world so much bigger” that breaking the law to survive “becomes less and less of an option.”

“It’s alluring for young women to think, ‘I can come to a place where folks really get me, and we have some collective struggles,’” Simon adds. Before, “they didn’t have a space” for services “where they weren’t being pathologized.”

For years, the Young Women’s Freedom Center led programs in juvenile hall and worked with teens who lived on the streets. Then, around 2014, a judge who ran a juvenile court in Silicon Valley’s Santa Clara County decided to visit. At the time, Judge Katherine Lucero, the daughter of farmworkers, worked for a “model court” that required her to come up with three reforms every year. She’d read that the Young Women’s Freedom Center reduced arrests for girls in the program—by 85 percent—and she wondered what she could learn from its methods. “How can we support these girls, but not have the court be the center?” Lucero wondered.

When Lucero arrived at the nonprofit’s headquarters, it was a far cry from the courtrooms she’d worked in, which positioned the judge as the focal point, the child waiting at a table with an attorney. Here, teens could relax on couches or get a snack. Young mothers could get free child care, and anyone could help themselves to a “self-care station” with condoms, pads, clothes, and toiletries.

Tae Thomas, an 18-year-old I met while touring the nonprofit, told me her advocate became like a sister to her, letting her spend the night or do laundry while Thomas was homeless. Other girls get linked up with therapists or free housing or take workshops on financial management. “It’s the opposite of court,” Lucero told me, so struck by the memory that she started to get choked up. Instead of “lining people up and talking at them,” she said, the center “appeals to the part that’s hungry for connection: You go in there and you feel like you belong.”

Lucero’s visit to the center changed the way she conducted her court. Whenever she had a detention hearing on her docket, she’d try to call someone from the center into the courtroom to talk with the girl: Would she like to skip traditional probation, the judge asked, and instead go through the center’s coaching program? Girls who said yes would receive a monthly stipend of $500 to $1,000 to help meet their basic needs, however they defined them. (Funding for the center’s stipends comes partly from public agencies in California.) “In my mind, I did not order them to participate as much as I asked them,” Lucero says. If the girl agreed, Lucero dismissed her case; there would be no punishment if she started the coaching and didn’t finish. “What is so powerful about the Young Women’s Freedom Center is that we have judges trusting it” and giving up some control, says Vera’s Rosenthal.

Their combined efforts appeared to pay off. For about a year during 2021 and 2022, Santa Clara County held no girls in long-term detention facilities, and no more than two girls in short-term facilities. The center has expanded to Oakland, San Jose, Los Angeles, and Contra Costa County, which have seen their rates of girls’ incarceration fall, too. Lucero now leads California’s Office of Youth and Community Restoration, a government agency that’s trying, among other things, to end the detention of girls statewide.

New York City is experimenting with a similar program called ROSES, developed by NYU’s Javdani, that pairs girls with university students who can help them advocate for their goals, kind of like the programs at Michigan State. It seems to be working: Researchers found that teens in ROSES are significantly less likely to engage in delinquent acts than kids in traditional juvenile justice programs. For at least a year and a half in 2021 and 2022, New York City had no more than two girls in juvenile placement facilities.

Such programs also save money, especially since juvenile incarceration can be two to five times as expensive as adult incarceration. The Young Women’s Freedom Center spends several thousand dollars a year to serve one girl. In most states, it can cost more than $100,000 a year on average to lock up a single kid. In California, where housing is so expensive, it can be triple that.

So what if we expanded this thinking beyond girls? What if, instead of stigmatizing people after their arrests, we asked them what they need to turn their lives around?

In 2023, Hawaii’s judiciary launched the Women’s Court in Honolulu, for women convicted of certain nonviolent crimes. Like Oahu’s Girls Court, it offers an empathetic judge and probation officers who have the time and training to offer real support. When I stopped by a hearing, Judge Trish Morikawa spoke so casually with the women that at times they seemed like friends catching up over lunch. “You look good!” she told one of them.

“I love the house, I just love it,” the woman said of her new digs.

When another woman started apologizing for “being a lot,” Morikawa tried to affirm her. “You’re not a lot,” she said. “Don’t ever apologize for what you need.”

At first glance, it would seem as if girls and women are the most likely to benefit from the advocacy model, because they tend to be convicted of nonviolent crimes. But NYU researchers recently examined dozens of juvenile justice programs and found that boys’ behavior improved much more in programs designed for traumatized girls than in traditional programs for boys. In fact, boys saw even more progress in these programs than the girls did, with greater reductions to delinquency, aggression, and other disruptive behavior. “Who couldn’t benefit from a more relation-focused, healing-centered approach?” says Jeannette Pai-Espinosa, who directs the nonprofit Justice and Joy, which works to reduce girls’ incarceration nationally.

In Texas’ Harris County, home to Houston, the judiciary created a girls court to help victims of sex trafficking, but it later changed the name and began including boys. That kind of move could make these programs more welcoming to gender-nonconforming teens, who constitute a surprisingly large portion of the justice system: Around the country, about 40 percent of kids whom courts identify as “girls” self-identify as LGBTQ, many of them transgender or gender expansive.

Of course, getting politicians to prioritize advocacy models is a tough sell. Nationally, violence shot up during the early days of the pandemic, and though it has since fallen to some of the lowest levels in decades, people remain deeply afraid of crime. Even Californians voted to roll back progressive criminal justice reforms last year, and ousted two progressive district attorneys who were more forgiving of teen offenders.

A rainbow appears during a Surfrider Spirit Session at Kuhio Beach in Waikiki, Oahu on November 10, 2024.Elsye Butler

A rainbow appears during a Surfrider Spirit Session at Kuhio Beach in Waikiki, Oahu on November 10, 2024.Elsye Butler

The country’s youth incarceration rate is also changing: After decades of steady decreases, it rose slightly in 2021 and 2022, the latest years for which we have data. When Judge Radius and I visited Hawaii’s Youth Correctional Facility last October, the girls’ housing unit was no longer empty; four kids were living there. “A lot of localities,” says the Vera Institute’s Rosenthal, are in “the last mile between ‘almost zero’ and ‘permanently zero.’”

Even so, more communities are starting to notice the benefits of keeping girls out of incarceration. With the money saved, Hawaii recently opened a homeless shelter and a human trafficking assessment center on its youth prison grounds*.* Deputy Warden Matelina Aulava guided me and Radius on a tour there, past fields where kids grow taro and breadfruit and a stable used for horse therapy. Aulava said she hopes that one day this place, which once served as a boarding school for Indigenous kids, stops incarcerating teens altogether and becomes a hub for social services. “What is it that we need to put at the front end” of the system? she added.

Although getting the population of teen lockups down to zero makes for good headlines, it’s only one part of the equation; it won’t be enough until communities help kids stay out of trouble in the first place. Radius told me that a few years ago, when the girls’ housing unit finally sat empty, she found her excitement tempered by a nagging worry that people might forget about the issue. Please don’t take this as a total success, she wanted to tell them, and assume we don’t need to think about girls anymore.

From Mother Jones via this RSS feed

Lily Tang Williams, a Republican House of Representatives candidate in the New Hampshire Second District, talks during a campaign stop in 2022. Charles Krupa/AP

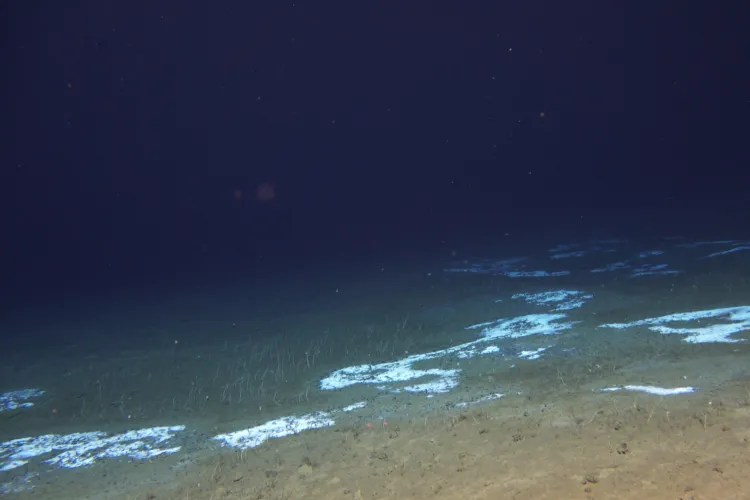

Lily Tang Williams, a Republican House of Representatives candidate in the New Hampshire Second District, talks during a campaign stop in 2022. Charles Krupa/AP Clusters of tube worms.Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS

Clusters of tube worms.Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS Collections of microbes at the bottom of a trench in the Pacific Ocean.Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS

Collections of microbes at the bottom of a trench in the Pacific Ocean.Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS

Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, CAS Kadreal Hebert, who moved to New Orleans about three years ago, is a school teacher. She has already attended several funerals for her students.Adam Mahoney/Capital B

Kadreal Hebert, who moved to New Orleans about three years ago, is a school teacher. She has already attended several funerals for her students.Adam Mahoney/Capital B Rita Gardner (right), who escaped the flooding on an air mattress because she cannot swim at the B.W. Cooper housing project in New Orleans, August 2007.

Rita Gardner (right), who escaped the flooding on an air mattress because she cannot swim at the B.W. Cooper housing project in New Orleans, August 2007. Robert Green Sr. sits in front of his FEMA trailer in the Lower Ninth Ward in August of 2007 with a memorial tombstone to his mother Joyce Green and granddaughter Shanai Green. Both were killed in the flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina.Mario Tama/Getty

Robert Green Sr. sits in front of his FEMA trailer in the Lower Ninth Ward in August of 2007 with a memorial tombstone to his mother Joyce Green and granddaughter Shanai Green. Both were killed in the flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina.Mario Tama/Getty Jacqueline Smith and her mother, Lucille Matthew, await transportation after they were rescued from their flooded neighborhood in the aftermath of Hurricane Ida in August 2021, in Laplace, Louisiana.Scott Olson/Getty

Jacqueline Smith and her mother, Lucille Matthew, await transportation after they were rescued from their flooded neighborhood in the aftermath of Hurricane Ida in August 2021, in Laplace, Louisiana.Scott Olson/Getty Kimber Smith at the FEMA Diamond travel trailer park in Port Sulphur, Louisiana, May 2008.Mario Tama/Getty

Kimber Smith at the FEMA Diamond travel trailer park in Port Sulphur, Louisiana, May 2008.Mario Tama/Getty Judge Karen Radius in Girls Court in Honolulu.Elyse Butler

Judge Karen Radius in Girls Court in Honolulu.Elyse Butler Probation Officer Tia Ikeno and Judge Dyan Medeiros of Girls Court at the Kapolei Courthouse on Oahu, Hawaii.Elyse Butler

Probation Officer Tia Ikeno and Judge Dyan Medeiros of Girls Court at the Kapolei Courthouse on Oahu, Hawaii.Elyse Butler Lateefah Simon, 32, executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, and is in her office in San Francisco.Liz Hafalia/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty

Lateefah Simon, 32, executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, and is in her office in San Francisco.Liz Hafalia/The San Francisco Chronicle/Getty A rainbow appears during a Surfrider Spirit Session at Kuhio Beach in Waikiki, Oahu on November 10, 2024.Elsye Butler

A rainbow appears during a Surfrider Spirit Session at Kuhio Beach in Waikiki, Oahu on November 10, 2024.Elsye Butler