Welcome to the first week of the Imperialism Reading Group!

This will be a weekly thread in which we read through books on and related to imperialism and geopolitics. How many chapters or pages we will cover per week will vary based on the density and difficulty of the book, but I'm generally aiming at 30 to 40 pages per week, which should take you about an hour or two.

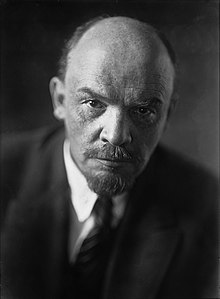

The first book we will be covering is the foundation, the one and only, Lenin's Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. We will read two chapters per week starting from this week, meaning that we will finish reading in mid-to-late February. Unless a better suggestion is made, we will then cover Michael Hudson's Super Imperialism, and continue with various books from there.

Every week, I will write a summary of the chapter(s) read, for those who have already read the book and don't wish to reread, can't follow along for various reasons, or for those joining later who want to dive right in to the next book without needing to pick this one up too.

This week's chapter summary is here.

This week, we will be reading Chapter 1: Concentration of Production and Monopolies, and Chapter 2: Banks and their New Role.

Please comment or message me directly if you wish to be pinged for this group.

Chapter 1: Concentration of Production and Monopolies

Capitalism’s most characteristic feature is perhaps the growth and concentration of industry into massive enterprises. Lenin quotes figures to this effect in Germany between 1882 and 1907; both in terms of concentration of workers and production. The latter is much greater due to massive businesses being more productive; less than 1% of businesses use over 75% of the steam+electric power. Lenin also quotes figures from America, demonstrating an even greater degree of monopolization, showing that it is an international trend.

A single massive enterprise can be part of many branches of industry, which makes them less reliant on trading between those branches (particularly when raw materials are expensive), which increases profits relative to other enterprises, leading to them becoming yet more powerful. Countries with high tariffs only further lead to monopolization. In countries with freer trade, such as Britain in Lenin’s day, monopolization instead occurs because once a massive, technically-advanced enterprise is established (with a massive amount of capital investment), it is harder to launch competing enterprises both due to the initial capital demand, and because a new enterprise would flood the market with new products, and - unless there is a sudden expansion in demand - the price of the products produced would not generate sufficient profit for either the new or old enterprise. Hence, Marx’s analysis that competition must lead to monopoly is proven correct.

Monopoly capitalism overcame competitive capitalism at the beginning of the 20th century, but it has a rich prehistory which begins in the 1860s. There was an international industrial depression from the 1870s to the 1890s. By the start of the depression, Britain had completed its construction of competitive capitalism and Germany was still the battleground between handicraft and industry. During the depression, the cartels slowly coalesced. At the end of the depression, these business cartels collaborated to take advantage of a brief boom in 1889-1890, driving up prices to their own ultimate detriment, leading to a five-year period of bad trade and low prices. This did not dissuade the cartels, but instead emboldened them, leading them to soon take control of entire fields of industry; mining most notably, initially. The cartel system acquired a coke syndicate, then a coal syndicate. By the 1910s, many industrial fields now no longer had free competition.

A cartel is a group of enterprises, businesses, etc, who use pre-arranged agreements to subvert market mechanisms, deciding the quantities and prices of goods and dividing profits between them. This is more efficient than markets, hence their growth. Some examples are the Rhine-Westphalian Coal Syndicate, which by 1910 controlled over 95% of all coal output in the area. Another is the Standard Oil Company in the US, and the United States Steel Corporation, which hire engineers specifically for inventing more cost-efficient production methods. The Tobacco Trust’s organisation is particularly enlightening; it formed subsidiary companies just to acquire patents, and its massive capital means it can form its own machine shops for various inventions in the field of cigarette production. Ease of access to raw materials is no substantial factor for monopolization; the German cement industry was highly cartelised into regional syndicates which raised prices, despite the ease of access to the raw materials for cement.

Eventually, all sources of raw material are analyzed, their yearly output predicted and divided up between enterprises, transportation methods are bought up by them, and they have near-guaranteed access to the most skilled labour. For new businesses that which to compete, their logistics are halted; unions are forbidden from working with them; prices are cut to ruin them (as the monopolies can better handle it than new businesses); boycotts are created; and many other underhanded and dishonest tricks. This is how the social order transforms from free competition to complete socialisation, to benefit a few. The bulk of profits now go to those adept at financial manipulation, such as speculators.

Cartels cannot abolish capitalist crises; on the contrary, they intensify them. As cartelised industries increase in strength, other industries suffer from an increasing lack of coordination. In this disparity, there is anarchy and crises. In turn, crises increase the tendency towards monopoly. For example, during the crisis of 1900 in which prices and demand fell, the non-cartel enterprises were in a precarious position, which barely affected the cartel enterprises, due to their durability, created by the magnitude of capital invested and the complicated methods of production that provide a significant barrier of entry to other enterprises.