Welcome to the first week of the Imperialism Reading Group!

This will be a weekly thread in which we read through books on and related to imperialism and geopolitics. How many chapters or pages we will cover per week will vary based on the density and difficulty of the book, but I'm generally aiming at 30 to 40 pages per week, which should take you about an hour or two.

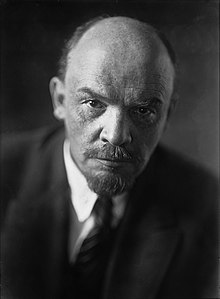

The first book we will be covering is the foundation, the one and only, Lenin's Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. We will read two chapters per week starting from this week, meaning that we will finish reading in mid-to-late February. Unless a better suggestion is made, we will then cover Michael Hudson's Super Imperialism, and continue with various books from there.

Every week, I will write a summary of the chapter(s) read, for those who have already read the book and don't wish to reread, can't follow along for various reasons, or for those joining later who want to dive right in to the next book without needing to pick this one up too.

This week's chapter summary is here.

This week, we will be reading Chapter 1: Concentration of Production and Monopolies, and Chapter 2: Banks and their New Role.

Please comment or message me directly if you wish to be pinged for this group.

Chapter 2: Banks and their New Role

Banks transform capital that is inactive into capital that can yield profit for use by the capitalist class.

When banks merely carry the current accounts of a few capitalists, it is a mostly technical and auxiliary operation. However, banks also undergo concentration and monopolization, meaning that they eventually come to possess vast amounts of the money capital of all larger and smaller capitalists in any one country; and, therefore, control over much of the means of production. This transforms them into something else entirely.

Lenin returns to Germany for an example, demonstrating a 40% growth in combined deposits from 1907 to 1912 among fairly large banks (above a capital of 1 million marks), while small banks become either squeezed out of the story or become branches of the larger banks. However, when looking at total bank capital, the nine biggest Berlin banks controlled over 80% of total German bank capital; and these massive banks have affiliated banks which they have acquired via purchase or exchanging shares, annexing them into their own groups/concerns. For example, Deustche Bank comprised 87 banks in some fashion.

In Germany, the six largest banks rapidly expanded at the turn of the 20th century, transforming thousands of scattered enterprises into a single national capitalist economy, then later into a world capitalist economy. These trends are only more advanced in older capitalist systems like in Britain and France. In the United States, two very large banks - Rockefeller and Morgan - control a capital of 11 billion marks; roughly comparable to those of the nine largest banks in Germany.

Bank monopolists are capable, due to their banking connections, to determine the financial positions of capitalists and then control them by restricting or enlarging them, or give or restrict credit. This gives them the power to either destroy them or increase their capital rapidly. Like with industrial enterprises, “competing” banks are often collaborators, forming increasingly durable agreements. In doing so, banks now control, directly and indirectly, much of the population of their countries; and agricultural capital stagnates and lags behind profitable heavy industries, to the detriment of the working classes. It is under this paradigm that even industry cartels can be commanded from yet higher in the economy.

The bank monopolists link up with the industrial enterprises and bank directors are appointed to the supervisory boards of industrial and commercial enterprises. This leads to increasing interdependency between banks and industry; for example, six of the biggest Berlin banks were represented by their directors in over 300 industrial companies and by their board members in over 400. These companies range across the whole of society, not merely heavy industry. The opposite also occurs, in which the supervisory boards of banks are staffed by industrialists. Additionally, bank monopolists collaborate with the state; supervisory board seats are sometimes given to members of parliament or city councillers.

At a certain level of power and concentration, this leads to a division of labour among the bank monopolists. Each director has his own special function; for example, a director may specialize in dealing with industry; or another with a certain set of specific enterprises with which he has good connections; or yet another with a foreign enterprise. This leads them out of pure banking, into becoming experts and analysts of fields of industry, or insurance, or commercial trade, and so on. This makes them more competent at those roles, resulting in better decisions, and thus more profit. This is supplemented by efforts to introduce experts to supervisory boards, such as the aforementioned industrialists. Indeed, one large French bank has a financial research service which has departments on many sectors on the economy. The largest banks become universal, without specialisation.

Lenin says that the turn of the 20th century marked the death of the old banking system of middlemen, and the birth of the new system of the domination of financial capital over industrial capital. Indeed, the crisis of 1900, right on the turn of the century, massively intensified this process, albeit with mergers taking place in the years before then.

The savings-banks and post offices are more decentralized, spreading to more remote places and wider sections of the population, and are beginning to compete with banks. But as they pay interest on deposits and seek profitable investments for their capital to provide that interest, they become more and more like the banks (and indeed become controlled by the very same banking monopolists).

Lenin remarks that larger banks become increasingly like stock exchanges; whereas before the 1870-90 depression the Stock Exchange was regarded by bourgeois economists as “youthful”, they are now essentially dominated by the big banks.