Welcome to the first week of the Imperialism Reading Group!

This will be a weekly thread in which we read through books on and related to imperialism and geopolitics. How many chapters or pages we will cover per week will vary based on the density and difficulty of the book, but I'm generally aiming at 30 to 40 pages per week, which should take you about an hour or two.

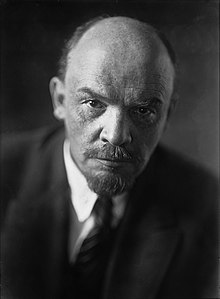

The first book we will be covering is the foundation, the one and only, Lenin's Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. We will read two chapters per week starting from this week, meaning that we will finish reading in mid-to-late February. Unless a better suggestion is made, we will then cover Michael Hudson's Super Imperialism, and continue with various books from there.

Every week, I will write a summary of the chapter(s) read, for those who have already read the book and don't wish to reread, can't follow along for various reasons, or for those joining later who want to dive right in to the next book without needing to pick this one up too.

This week's chapter summary is here.

This week, we will be reading Chapter 1: Concentration of Production and Monopolies, and Chapter 2: Banks and their New Role.

Please comment or message me directly if you wish to be pinged for this group.

I guess I'll offer some metatexual/paratexual (?) commentary:

From the prefaces:

Far from some holy text, Lenin himself felt the final work was compromised due to having to write the work in such a way that it would sneak past Tsarist censors. We ought to read the work with a much more critical eye because there's the literal text and there's what Lenin is really trying to say between the lines that the Tsarist censors won't catch. This also shows how so many people engage in book-worship. Yes, this text is absolutely foundational in understanding imperialism, but it does no good to put this text on a pedestal when even the author himself admits that he can't read it without cringing slightly at certain parts. This is why the prefaces along with the companion piece "Imperialism and the Split in Socialism" are also important to read as well.

I'll go over some of the banking institutions Lenin mentioned:

Those three French banks more or less existed until 1966 when Comptoir National merged with another bank to form Banque Nationale de Paris. Crédit Lyonnais, BNP, and Société Générale then existed until 2000 when BNP merged with another bank to form BNP Paribas. Around 2002, Crédit Lyonnais almost got absorbed by BNP Paribas but in the end got taken over by another French bank called Crédit Agricole, which Wikipedia calls "the second largest bank in France, after BNP Paribas, as well as the third largest in Europe and tenth largest in the world."

The final conclusion of the increasingly durable character was met when Deutsches Bank merged with Disconto-Gesellschaft to form Deutsche Bank und Disconto-Gesellschaft in 1929. They changed their name back to Deutsche Bank in 1937, presumably because calling yourself "German Bank" plays well in Nazi Germany, which they aggressively collaborated with, including taking over Austria's largest bank after the Anschluss.

And now that I think about it, it's somewhat curious that Lenin would focus more on German banks when the center of capital during the late 19th/early 20th century wasn't in Berlin, but London (or I guess Washington DC if you're one of those people who argues that the center of capital had already moved to the US by the early 20th century). To really understand how 19th century finance capital operates, why would you focus on German banks instead of British banks? Could it be that because Russia was allied with the UK during WWI against Germany, those Tsarist censors were more tolerant of someone shitting on Russia's enemies instead of Russia's allies?