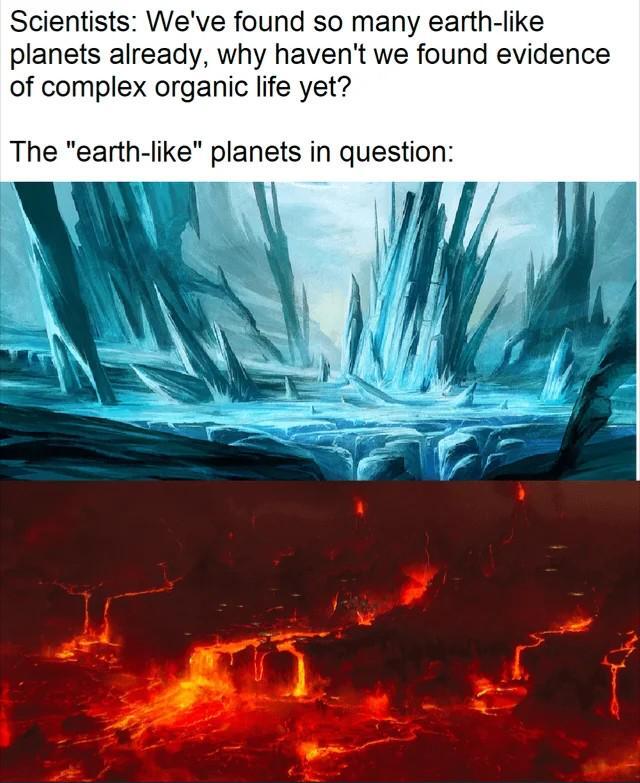

Remember Venus is a Earth like planet and even relatively close to the habitable zone (depending on your definitions and error bars). Just because it's a planet like Earth, doesn't mean it would support life.

Science Memes

Welcome to c/science_memes @ Mander.xyz!

A place for majestic STEMLORD peacocking, as well as memes about the realities of working in a lab.

Rules

- Don't throw mud. Behave like an intellectual and remember the human.

- Keep it rooted (on topic).

- No spam.

- Infographics welcome, get schooled.

This is a science community. We use the Dawkins definition of meme.

Research Committee

Other Mander Communities

Science and Research

Biology and Life Sciences

- !abiogenesis@mander.xyz

- !animal-behavior@mander.xyz

- !anthropology@mander.xyz

- !arachnology@mander.xyz

- !balconygardening@slrpnk.net

- !biodiversity@mander.xyz

- !biology@mander.xyz

- !biophysics@mander.xyz

- !botany@mander.xyz

- !ecology@mander.xyz

- !entomology@mander.xyz

- !fermentation@mander.xyz

- !herpetology@mander.xyz

- !houseplants@mander.xyz

- !medicine@mander.xyz

- !microscopy@mander.xyz

- !mycology@mander.xyz

- !nudibranchs@mander.xyz

- !nutrition@mander.xyz

- !palaeoecology@mander.xyz

- !palaeontology@mander.xyz

- !photosynthesis@mander.xyz

- !plantid@mander.xyz

- !plants@mander.xyz

- !reptiles and amphibians@mander.xyz

Physical Sciences

- !astronomy@mander.xyz

- !chemistry@mander.xyz

- !earthscience@mander.xyz

- !geography@mander.xyz

- !geospatial@mander.xyz

- !nuclear@mander.xyz

- !physics@mander.xyz

- !quantum-computing@mander.xyz

- !spectroscopy@mander.xyz

Humanities and Social Sciences

Practical and Applied Sciences

- !exercise-and sports-science@mander.xyz

- !gardening@mander.xyz

- !self sufficiency@mander.xyz

- !soilscience@slrpnk.net

- !terrariums@mander.xyz

- !timelapse@mander.xyz

Memes

Miscellaneous

I wouldn't be particularly surprised to find out Venus has life. Complex life, probably not, but something like the life we have around undersea volcanic vents seems more than possible.

I really don't see how. Yes there is life at undersea volcanic vents on Earth, but they don't live like in the vent itself. It's where the temperature gets lower there is life.

As far as I know nothing can survive boiling temperatures for long and Venus has been way above boiling for millions of years. There are extremophiles that survive a little above boiling, but 400+ degrees I really don't see how.

There is a chance in the atmosphere where there are parts with reasonable temperatures and pressures. But there is also a lot of acids floating around, which is sorta incompatible with life. If some photosynthetic life was present in the atmosphere, floating around and living on sunlight, we would have seen it by now. There would be seasonal blooms, similar to plankton in the oceans on Earth.

It's cool to think about and I remember reading old sci-fi with Venus as a forest planet, since it's so like Earth in a lot of ways. But in reality it's dead dead.

Same for Mars I feel like. We might find indications life once lived there, which would be a huge deal. But as far as actual current life, I think chances are slim to none.

The mean surface temperature of Venus is only 464C.

But, with 93x the atmospheric pressure of earth, water boils at around 300C.

So…what is it that makes it difficult to thrive beyond 100C? Is it strictly the temperature, or is it the properties of water at that temperature? If it’s the latter, I wouldn’t be so surprised.

Also keep in mind that photosynthesis was a genetic accident that just happened to work really, really well, and the ability to process sunlight directly into energy was what allowed microorganisms to move away from thermal vents.

That same genetic accident could play out in a different world. Or a different genetic accident that’s more suited to their environment. Or no genetic accident at all, and life never moves past small, very secluded regions.

It's the temperature, a lot of chemistry doesn't work at higher temperatures because everything is too unstable. There is simply too much energy messing things up. This is why having a surface temperature that allows for liquid water to be present is such a good indicator for life. A lot of chemistry for life as we know it works at liquid water temperatures and water does play a big part as well.

The pressure would be less of an issue, there is plenty of life on Earth that thrives at huge pressures.

I'm pretty sure life on Earth evolved at the surface (or even in the atmosphere, it is thought lightning plays a part) and only adapted to use the vents later on. I'm not sure life could get started at those volcanic vents.

The pressure would be less of an issue, there is plenty of life on Earth that thrives at huge pressures.

I think their point was that the pressure "balances out" the temperature - so that enough of these chemistry does remain stable even though the temperature is high. For example - the water remains liquid because of the pressure, so that's one requirement for life that gets fulfilled.

Life finds a way...

As far as I know nothing can survive boiling temperatures for long

Pretty sure there are though

The article you post specifically states the observed lifeforms to be limited to 130 degrees C (and even then they don't live long) with a theoretical max of 150 degrees C. Life as we know it (in all its wonderous forms) cannot exist above that temperature. The processes needed simply can't work and the structures can't exist. Maybe there's some lifeform that uses a neat trick to remain alive trough a short stint of say 200 degrees, but that's a far cry from living at 400+ all the time. Extremophiles usually can't live at boiling temperatures for long, they can only tolerate it for short durations, living most of their lives in less than 100 degrees. Which is still really cool, since most lifeforms die at half that temperature.

Now there could be some form of exotic stuff that may be called life, but that's well into speculation and science fiction.

Personally I'm not convinced by extremophiles, yes they can exist in very harsh environments, but they are always specialized forms of life that evolved in simpler conditions. It's not clear whether life can make the jump from mild to extreme or even start out in an extreme environment. My bet is that's not possible. So that could mean stuff on Mars, since we know it was probably very mild in the past and extremophiles may have persisted that can live in the current environment since that time (unlikely, but possible). But probably not on places like Venus where as far as we know it's been super hot for ages now, too long for anything to survive if it was even habitable to start with.

To me it feels that if the planet cannot support life, then it's not an Earth-like planet. So, the definition of Earth-like planet is broken

Show me the scientists who are surprised by the fact that we haven't found life on another planet yet. Where are those scientists? Are they even real?

I mean, isn't the entire concept of the Fermi paradox that given the universe is so large and old, it seems surprising that we see no signs of aliens anywhere, and therefore some explanation must exist for why we have not? That's more focused on intelligent life than extraterrestrial life of any sort I suppose, but given it's even named a paradox in the first place, someone must find it surprising

In addition to the other helpful replies, one of the major flaws of the Fermi paradox is that it fails to account for the vastness of time. Our failure to observe spacefaring intelligent life is the metaphorical equivalent of a baby born at some point in human history somewhere on earth, opening it's eyes only long enough to blink, and not observing Cher. It doesn't mean that Cher doesn't exist, or even that Cher should be observable given that humanity is so large and old.

My favourite is the idea that it takes time to build out the "infrastructure" that allows for life. Basically, no supernovae, no life, not enough supernovae, extremely low probability of life. Even if that doesn't put Earth's life near the leading edge, we may be on the leading edge of technological civilizations.

I'd also point out that we've nearly wiped ourselves out several times, and we're headed towards making our planet incompatible with life. If the conditions for life exist AND life evolves to be sentient AND the sentient life develops communication AND the communication fosters cooperation AND the cooperation leads to technology AND that technology allows the life to survive the vastness of space AND the technology allows for interstellar travel, all that progress could end with a meteor or a virus or a particularly strong solar storm that blows through the magnetosphere and takes our atmosphere with it.

The conditions for sentient technological species exist on earth, and humans are the only ones even close to surviving in space. Dolphins, octopodes, dinosaurs, corvids nothing else is even sharing arbitrary knowledge yet. For that to even happen, we'd probably all need to be dead.

My argument of that is that we've only just started looking in a massive, massive, massive universe. Like, the other day. The big bang theory is less than a hundred years old and we only just discovered cosmic background radiation in 1964

We JUST started looking and we probably have no idea what we are looking for or at.

Also, these earth like planets are a fucking guess, a giant maybe. They make their host star, which we make assumptions of about their size, make a tiny hardly perceptible dip in light and we measure the wavelengts that were filtered out.

The more I learn about how this science is done, the more it all just looks like a big fucking maybe that someone spouts so confidently as fact. Like, the track record for fact is pretty thin in science.

The Fermi Paradox feels like someone sticking their finger in the water at the beach and confidently declaring there are no whales in the ocean because they didn't touch one.

I guess people tend to look to astronomers for information about space, while the Fermi paradox probably borders more on philosophy than on astronomy. And in a lot of people minds philosophers are not real scientists, unlike astronomers.

Science and Philosophy might not be exactly the same thing, but there is a lot of overlap, and a lot of people who do both.

An overwhelming portion of what is hard science now was probably in the domain of philosophy once.

You don't even have to go very far back to hit a time when scientists were called "natural philosophers".

And "philosopher" is just Ancient Greek for "lover of wisdom".

Science is generally a superset of philosophy if you try hard enough...

Earth was like those planets at various points in time.

like when the whole world froze https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ordovician

or thousands of years of lava pouring out https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permian%E2%80%93Triassic_extinction_event

Thousands of years of lava? Try millions, shortly after the earth's formation and collision with Theia, forming the Moon.

It could just be that they're just so far that we're looking at these planets millions/billion of years in the past, meaning there may may be life there but we can't see it yet.

Earth looked pretty icy when it was "snowball Earth" and early Earth's surface was full of molten rocks.

The Milky Way galaxy is "only" 100.000 light years across, so any planets we see around stars in our galaxy we would only see about at most 100.000 years in the past. So it would be very unlikely there would be detectable life now, where there wasn't 100.000 years ago. And even if there were, it wouldn't be complex life.

The most distant exoplanet we've found to date is 27.710 light years away, so we see that planet as it was 27.710 years ago. We've had humans running round for at least a 100.000 year on Earth, so if there are any aliens on that planet we would see them.

Almost forgot the mandatory XKCD reference: https://xkcd.com/1342/

It's worth mentioning that we can't "see" any exoplanets at all. We know they are there by the gravitational lensing that occurs when a planet passes in front of the star it orbits. Once we calculate the position and orbit, we can track the planets and listen for any radio waves or radiation that would indicate life. We are also getting better as guessing the chemical composition of the planets, but it's not like we can scan the surface for plants and animals.

That's one way of detecting exoplanets, but not the most common one.

There are a couple of ways we can detect exoplanets:

We can see a wobble in the position of the star, as the star and the planet orbit around their common center of mass, which is offset from the center of mass of the star due to the mass of the planet.

Another way is to observe the light from a star, as the planet passes in front of the star some of the light gets blocked by the planet. By measuring the time and amount of light blocked, we can tell a lot about what is doing the blocking. The benefit of this method is some light passes through the atmosphere of the planet (if it has a significant atmosphere), by analyzing the spectrum we can tell what the atmosphere is made from.

We can also literally see a planet by direct observation, by blocking out the light of the central star, we can see light bouncing off the planet and observe that directly. This is hard, but has been done with several exoplanets.

There are more ways, see this Wikipedia article as a jumping off point for learning all about it: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Methods_of_detecting_exoplanets

There's always a relevant xkcd!

Yeah I didn't know we were mostly looking at planets in the Milky Way, but it makes sense. Rocky planets are very tiny compared to other stuff in the universe so it's gotta be hard detecting them millions of light years out.

Yeah it's hard to even make out individual stars in other galaxies, let alone planets around them.

Only chance we have of seeing life in other galaxies is if they have built stuff like Dyson swarms.

There are places on earth that look likes both of those pictures

Wake me up when they find a Class M planet.

Yo, is that second picture Mustafar?

It totally is, good eye

Be patient. We're getting there