Collective Shout, an organization “for anyone concerned about the increasing pornification of culture,” based its claim that Steam and Itch.io host “hundreds of rape and incest games” on user-generated tags, and the organizations that co-signed Collective Shout's open letter to payment processors did not respond to 404 Media’s questions about whether they tried to verify its accusations against the game platforms before signing on their support.

Collective Shout's July 11 letter urged Paypal, Visa, Mastercard, Japan Credit Bureau, Paysafe, and Discover to "cease processing payments on gaming platforms which host rape, incest and child sexual abuse-themed games."

On July 15, Steam, a digital storefront for PC games operated by Valve, updated its guidelines to ban “certain kinds of adult content,” blaming restrictions from payment processors and financial institutions. And on July 23, Itch.io, a massively popular indie game store, delisted every game marked NSFW so that those games will no longer be indexed in search results or appear on main pages, but re-indexed free adult NSFW content on Friday. “We are still in ongoing discussions with payment processors and will be re-introducing paid content slowly to ensure we can confidently support the widest range of creators in the long term,” the site’s founder Leaf Corcoran said in an announcement.

Itch.io also blamed pressure from payment processors—which in turn have been pressured by a campaign spearheaded by Collective Shout, a “grassroots campaigns movement against the objectification of women and the sexualisation of girls,” according to its site.

“Most of the content found within the games, including the graphics and the developers descriptions, are too distressing for us to make public,” the letter says. “A Collective Shout team member has conducted extensive research using a Steam account set up for this purpose. She has documented content including violent sexual torture of women, and children including incest related abuse involving family members.”

I asked Collective Shout if it would show me the research, name any of the 500 games they found other than No Mercy, or disclose what that research entailed. “We found almost 500 other games tagged with rape or incest on Steam. Some of these included extreme sexual torture and abuse of women,” Caitlin Roper, campaigns manager at Collective Shout, told me in an email. "Given Steam had not responded at any point, we wrote an open letter to payment processors asking them to stop processing payments on gaming platforms which host rape, incest and child sexual abuse themed games. This letter was signed by leaders in the field, including academics, advocates and experts on violence against women and children." Roper did not disclose any specifics about the group's research. I asked Roper if the Collective Shout team played any of those tagged games to check the context of the content, and did not receive a response.

Steam tags, however, are assigned by players, not developers. They’re frequently trolled, with users assigning inappropriate tags to games with unrelated content. Keywords and tags have never been a useful metric for distilling nuance. Collective Shout is repeating history: In the early days of the internet, a researcher successfully fomented one of the first mainstream internet porn panics by claiming that bulletin boards were full of extreme sexual material that children could access.

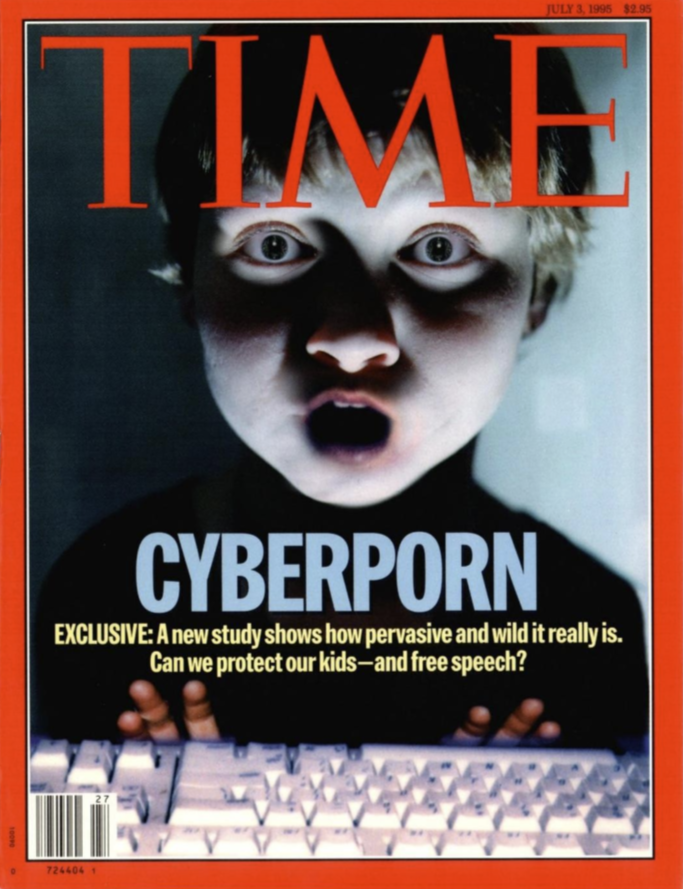

In 1995, a Carnegie Mellon engineering student, Marty Rimm, claimed that he surveyed 917,410 “sexually explicit pictures, descriptions, short stories, and film clips” from across the internet. More rigorous researchers and online freedom of speech advocates at the time tore his “research” and the subsequent salacious Time magazine article about it apart.

They found that Rimm didn’t examine most of Usenet or the internet at large, but was looking primarily at adult-oriented bulletin boards, which were often behind a paywall (an adult would have to call a board administrator and give them their credit card number, in many cases) or otherwise difficult for children to access. “Further, of the 917,410 files, all text and audio files were deleted from analysis, and only a very small number of images were actually examined,” technologist and academic J. Metz wrote in a paper examining the Rimm report in 1996. “The actual number of descriptions of images retained for the content analysis on which the study’s conclusions are based was 292,114.” Rimm found only nine websites (out of the more than 11,000 sites on the Word Wide Web at the time) that could be classified as R or X-rated, Metz noted. Attorney and longtime internet rights activist Mike Godwin, who was one of the many researchers who analyzed the Rimm report, told me that Rimm was likely only looking at text descriptions of images from adult BBS files without looking at their content, and assumed that those descriptions were accurate. But people often trolled the descriptions of files in bulletin boards or cracked jokes in them—in much the same way Steam tags are trolled by users.

Time ran the most salacious possible angle of the poorly conducted report (the author of that story has since said he regrets it), and religiously affiliated groups that already wanted to stop porn from becoming mainstream on the internet took hold of it. Senator Chuck Grassley brought the July 3, 1995 Time issue to the senate floor for a hearing about the Communications Decency Act, which would amend the Telecommunications Act and hold internet service providers, including BBS owners, liable for any content transmitted that could be interpreted as "obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, or indecent."

The Time July 3, 1995 'Cyberporn' story spread. Accessible in full at the Internet Archive

The Christian Coalition, a conservative grassroots political organization founded by Pat Robertson, also jumped on the report and used it to lobby for internet restrictions based on it. “The Religious Right is only a few weeks away from final victory in its effort to shut American citizens out of the Internet as a medium for uncensored communication,” technologist Howard Rheingold wrote at the time. “Discourse on the Net will be restricted to that which is judged suitable for young children in strict households.”

As journalist Ana Valens first reported in her investigations into the Collective Shout campaign (and the group’s claim that its open letter sent to payment processors successfully convinced them to pressure the platforms into changing their policies for adult games), several co-signatories of the letter are anti-porn groups that have pushed for broader legislation against the adult industry. (Valens’ articles on this topic were removed by Vice after publication.)

Haley McNamara, Senior Vice President of Strategic Initiatives and Programs at the National Center for Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE) signed the letter. NCOSE, formerly known as Morality in Media, has long pressured payment processors to remove support from adult content creators. The organization has also lobbied in favor of age verification laws that have spread to more than 30 states in the U.S., which experts say are not only invasive of everyone’s privacy but are ineffective at best, and only exacerbate problems of piracy, nonconsensual abuse material, and exploitation.

I asked NCOSE whether they directly viewed the content Collective Shout mentioned in its letter—or if they’d looked at the organization’s research themselves—before signing it. “Collective Shout collected and analyzed the materials and can best speak to everything they found,” a spokesperson said.

Helen Taylor, Vice President of Impact at Exodus Cry, also signed the letter. Exodus Cry is an organization that aims to end the “commercial sex industry.” In September 2020, Exodus Cry helped a campaign called “TraffickingHub” gather two million signatures on a petition to shut down Pornhub. “We’re calling for Pornhub to be shut down and its executives held accountable for these crimes,” the petition said—rhetoric echoed by extremist online groups that then called for the sentencing and execution of adult industry executives. Exodus Cry’s goal is to support laws that “end the sex industry,” as they write on their website. “We are asking political powers to enact and enforce laws that will eradicate exploitation in the sex industry and eliminate sex trafficking. This is absolutely necessary to restore and preserve freedom and justice in society.”

Exodus Cry did not respond to requests for comment.

Even if and when the tags are accurate, “rape” and “incest” themes in media, whether it’s literature, visual arts, personal memoirs, or games (which are often a combination of these things, especially from indie developers) can represent a range of themes that’s impossible to define. Talking about one’s own sexual abuse is not the same as glorifying sexual abuse, but relying on keywords and tags creates that false equivalency, and seems to be what Collective Shout relied on for its pressure campaign.

Meanwhile, game makers and consumers are caught in this warpath.

“Many trans and queer folks either lived off of or supplemented their income with their earnings on Itch,” Boarlord, an indie game developer who makes choose-your-own-adventure games that she describes as “deeply furry, deeply trans, deeply filthy,” told me days before Itch re-indexed those games. “If these restrictions remain, it means the blanket end of so many livelihoods. This sinks us deeper into economic precarity and our cultures, into obscurity or oblivion, dealer’s choice.”

I asked Boarlord if she thinks tags are a reliable way to understand what’s in a game. “Absolutely not,” she said. “I think there’s something truly profane about flattening an experience—art, entertainment, porn, whatever—to a handful of keywords. All of us live in a world dictated by an apparatus of punishment and surveillance. Because of this apparatus, whatever convenience tagging offers is immediately undermined by its ability to surveil and round us up. We have to dismantle the apparatus first, otherwise we’ll always end up here.”

Ted Litchfield, a journalist at PC Gamer, noted that the “nearly 500 other rape and incest games” figure Collective Shout cites in its own timeline of the campaign doesn’t make sense, and the only way to arrive at it would be to count duplicates, DLCs, and unrelated games removed in that time. “Counting up all ‘Removed’ and ‘Retired’ games on SteamDB since the 15th, I got 456 hits, but that includes double counts for most of the offending games (many of which were both ‘Removed’ and ‘Retired’), DLC and demos for those games (also given the double-r treatment), and a number of unrelated games that were taken off Steam during this time,” Litchfield wrote.

“No one platform nor marketplace should be responsible for so much media. We’ve concentrated too much of our culture to a handful of platforms like Patreon, Steam, and even Itch, though the latter, in my opinion, is less concerned with monopolization,” Boarlord said. “That makes them strategic targets for bad faith pressure campaigns. And in the case of Itch, they’re so small and lacking in resources there’s no leverage against the likes of Stripe, Visa, MasterCard. Sex workers have run our throats hoarse screaming about this: With the power to demonetize platforms that so many queer and trans people rely on to survive, payment processors effectively dictate our culture now. Visa, MasterCard, Stripe, Paypal, they decide who lives and dies.”

Visa, Mastercard and PayPal did not respond to my request for comment on the open letter or about whether they reviewed the contents of the games. Mastercard published a statement on August 1: "Mastercard has not evaluated any game or required restrictions of any activity on game creator sites and platforms, contrary to media reports and allegations. Our payment network follows standards based on the rule of law. Put simply, we allow all lawful purchases on our network. At the same time, we require merchants to have appropriate controls to ensure Mastercard cards cannot be used for unlawful purchases, including illegal adult content."

From 404 Media via this RSS feed

Andrea McCallin / Disney / Getty

Andrea McCallin / Disney / Getty

Illustration by Joshua Nazario

Illustration by Joshua Nazario The freestyle-motocross rider Taka Higashino does a no-hands “Superman” trick on opening day of the US Open of Surfing, in California. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times / Getty)

The freestyle-motocross rider Taka Higashino does a no-hands “Superman” trick on opening day of the US Open of Surfing, in California. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times / Getty)