Subscribe here: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Overcast | Pocket Casts

Soviet dissidents have long admired the United States and its Founding Fathers for their attachment to a moral core, the basis for individual human liberty. So what happens when American power is used not for moral interests but for solely pragmatic ones?

Host Garry Kasparov is joined by George Friedman, founder and chairman of Geopolitical Futures, a firm that analyzes foreign policy and forecasts global events. George’s view of the world—drawn from the experience of his family fleeing Nazis in Eastern Europe—echoes Henry Kissinger’s geopolitical philosophy: realism, not idealism. Garry and George consider whether realism is realistic, and what the future of American foreign policy means for democracy at home.

The following is a transcript of the episode:

[Music]

Garry Kasparov: The tradition of Soviet dissidents, those brave souls who spoke out against the totalitarian Communist regime, was based on morality. They often sacrificed their freedom, and even their lives, to call out the evils of a government that mentally and physically enslaved its own citizens and waged imperialistic wars abroad.

Andrei Sakharov, the father of the Soviet H-bomb who later won the Nobel Peace Prize for his criticism of the Communist regime, was banished for speaking out for human rights. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the writer who won the Nobel Prize in literature, was exiled for documenting the Stalinist Gulag system of prison camps and torture.

Their legacies inspired me, as did the great foe of the U.S.S.R. I grew up in: the United States of America. Solzhenitsyn in particular was a great admirer of the U.S., where he toured to huge audiences, speaking about the horrors of the Communist system. He spoke about the genius of the American Founding Fathers. He praised them for not becoming detached from a moral core, the basis for individual human liberty.

Ironically, the most powerful American foreign-policy voice of the second half of the 20th century largely disagreed with this high praise. It was the heavily accented voice of Henry Kissinger, President Richard Nixon’s secretary of state, who spoke not about good and evil, or even right or wrong, but about pragmatism, rational actors, and national interests. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Kissinger’s belief in realpolitik defined a generation of U.S. foreign policy. I often find it too cynical. Is realism really realistic? How can American power be used only for U.S. interests if America’s leaders cannot agree on what those interests are? Will we defend our allies against aggression as promised, or pragmatically decide on what suits us at the moment?

From The Atlantic, this is Autocracy in America. I’m Garry Kasparov.

The space between crusading global policeman and “America First” isolationism is where my guest this week plants a flag of analysis and concrete interests. George Friedman is the founder and chairman of Geopolitical Futures, a firm that analyzes foreign policy and forecasts global events. And he is something of the intellectual successor to Kissinger’s view of the world: realism, not idealism. George’s life of strategic analysis provides unique insight into what drives U.S. foreign policy—at least when it’s not being driven by Donald Trump’s social-media posts.

[Music]

Kasparov: George, hello.

George Friedman: Hello.

Kasparov: Thank you very much for joining our show. I was looking very much to talk to you about, of course, geopolitics, about the issues where you are one of the great experts. But before we dive into this discussion of the intricacies of geopolitics, I wondered if I might start with a more personal question. You were born in Hungary, and you left Hungary. Very early age.

Friedman: Yes.

Kasparov: You have no memories of Hungary, but your parents did. And how much did it affect your upbringing—the memories of Hungary, the war, and all these tragedies surrounding the war? Did it make a contribution to your views of the world? So just tell us a bit more about it.

Friedman: Well, I certainly grew up in a house where both my parents were in the Holocaust. My father was in Mauthausen, my mother in a little camp of Lichtenburg. They came back devastated. Then the Communists wanted to arrest my father because he had been a social democrat in a previous life. He was on a list. We escaped by taking a boat across the Danube to Czechoslovakia. And then we were to Vienna, where an American charity took us, gave us dinner, gave us a shower, gave us clothes and a room to live in. Until we got a visa to the United States. But also one of the defining points was 1956, when the Hungarians rose up on the same night my sister was married. And at that marriage everyone was Hungarian, and everyone was looking at the newspapers and the pictures trying to pick out which houses they lived in.

Kasparov: Very interesting. What was the mood in the room?

Friedman: Deep but controlled fear. Everyone in that room had been in the Holocaust. Everyone understood fear. Everyone was able to subdue it, control it. Everyone was watching what would happen. What they thought would happen would be a devastation of Hungary and the people they left behind, but also a possible devastation of Europe again. And these things were all their past. The Hungarian Revolution came very fast and went very fast, in a matter of days. The panic was there, but a clear understanding was not there in my family. Everybody was concerned only about whether this aunt or that uncle or that cousin was safe. It became a very personal event here in the United States for the Hungarian community, rather than an ideological one or anything like that.

Kasparov: Now you talked about your family’s tragic experience with Nazis. And now you’re talking about another tragic page in Hungarian history. It’s the Soviet invasion and brutality of Soviet troops. I assume that you are not feeling uncomfortable being both anti-fascist and anti-communist.

Friedman: Well, how could I like either one? One almost destroyed my family. The other was planning to destroy my family.

Kasparov: But what do you tell people that now, these days, are trying to separate these two?

Friedman: Well, one of the things I have learned is not to have many opinions. We have opinions, and then we wish for things to be the case. Then we shape our vision of the world based on those opinions. And the world usually doesn’t work that way. So in my life, when I asked a question about fascism, I’m more interested in what it was and why it emerged. I look the same way at the Soviet Union, at Communism. For me, the foundation of what I’ve learned is to avoid passions and to avoid opinions.

I want to understand why they do this. I don’t think that nations simply decide to be evil or good, or any of these things. Certain forces occur within nations. It is simply the way in which geopolitics, which is my field, emerges. Hungary was Hungary. Its position was its position. It was perpetually the victim. Russia was perpetually large, powerful, capable. Each nation had its fundamental definition, and that definition pivoted around power—the ability to be a nation, to make decisions for yourself and not have other countries impose them on you, so on.

So I try to understand the process that takes place. And that I am anti-Nazi does not mean I don’t want to understand very clearly why the Nazis arose, and I cannot do that unless I’m willing to put my head in the head of the Nazis, of those who supported them. But to me, the emergence of communism, the emergence of the Nazis, this is what I try to understand. Because I grew up in a house full of opinions. Hungarians, Jews living in one house. You have many opinions, many different ones going all over the place, and they think it matters. Yet in their lives, all the opinions they had didn’t matter. Had they been able to analyze the situation to understand what was happening, to put themselves in the other person’s monstrous position, they may have been safer. So from my point of view, opinions cloud understanding of what is going to happen. It can be very dangerous and really make it impossible for you to realize just how terrible they are or how not so terrible or whatever, and make decisions based on that.

Kasparov: Hmm. As an expert both from theory and from practice, having faced the horrors indirectly of Nazism through your family experience and also indirectly from communism, though you have been dealing with this as an American expert for many decades. Many people thought that fascism has ended in 1945. Many, myself included, thought that communism was decisively defeated in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union. It seems to me now that both ideologies are just very much around; they are even thriving. How do you explain that?

Friedman: Well, I don’t see Nazism thriving. I see authoritarianism thriving in the sense that in many cases it is seen by people that democracy, liberal democracy, is a failure. So I don’t see fascism, which had a particular ideology, being what’s at stake here. The fundamental question is whether liberal democracy in the way it is practiced now binds people together or drives them apart.

Authoritarianism, historically, is far more the norm than liberal democracy. Liberal democracy opened the door to the idea that people with very different beliefs—both in how governance should take place, how they should live their lives—could live together. It is a great experiment, but it’s a very difficult experiment. If you are a fundamental moralist—if you believe that the way you think things should be, or that the way you should live, is a moral imperative—then it is very difficult to have a liberal democracy.

Kasparov: Let’s for a moment jump back to Russia. Does Putin’s rule qualify to be called fascist dictatorship?

Friedman: Well, I think he is a Russian ruler in a very strange position. The czars had a history of this sort of rule and an ideology. The Soviet period had an ideology that justified the ruler. He has no visible ideology but nationalism, and he has no legitimate ideological validation. He has power, but even looking at his power, it’s very strange. Around him there seems to be no orderly structure, so that if tomorrow he died of a heart attack, it is not clear what the succession would be, what the process would be. So it’s a very odd governance, even for Russia. Because Russia to me has always been a place of deep ideology, of belief of something, of orthodoxy or of Marxism or what have you. Now it is a place without beliefs beyond the idea that Putin is in charge.

Kasparov: Going back to the decades of the Cold War, you were an American, and I understand you had a few people that listened to you. And you already had a massive reputation backing your expertise. But what is your view of the Cold War? Because for many, myself included, it was an ideological battle. Do you think that ideology played a crucial role or even an important role? Or ideology was simply a cover-up for other interests that were based, as we already discussed, on historical predetermination, and some patterns that have been established over decades, if not centuries?

Friedman: Well, we have to look back to the beginning. I don’t see the Cold War as a stand-alone war. It was what followed the Second World War, which in turn follows the First World War, which in turn follows the Napoleonic Wars. So Europe and the world is a place of a continuity of struggles. When I look at the United States, there is something unique about the United States. The fundamental interest of the United States, of the two oceans—the Atlantic and the Pacific—that is our barrier. We did not enter World War I until the Germans started sinking American ships and British ships with Americans on board. We did not enter World War II until the Japanese attacked us in the Pacific. And then, remember, the Germans declared war on us. We didn’t declare war on them. When the war ended, the United States had one fundamental geopolitical fear: that the Soviets would reach the west coast of Europe, and Cherbourg and Bremen and others would become Russian ports and challenge us in the Atlantic. From the American point of view, the problem of the Cold War from the United States was certainly the love of democracy, but it was also the fear of another war forced on us by an attack in the Atlantic. So if we could keep the Russians far back, this was essential.

So when I look at the Cold War, I look at the American imperative to keep the Russians away from the Atlantic. I look at the American imperative to forge out of Europe a defensive phase, and I look at the issue of the fight for the inheritance of the European empires, which took place between the Russians and the Americans and the third world, all over the place. So I see in an ideological element, which is a very good justification for what we ruthlessly did. And I see ideology as a moral imperative, but life and death is also a moral imperative.

And from the American point of view, what happened in Pearl Harbor, what happened in World War I and World War II, was the only thing that could threaten our existence. And therefore there was certainly a moral dimension to it. But there was also a geopolitical force that drove this. And I think we cast it as a moral imperative because that’s more persuasive to people. So by pitting it as a question of liberal democracy versus suppression, it was an added dimension. And I think American policy makers profoundly believed that—that this was the only issue. So there were two modes of thought about the Cold War. There was an American view that was very coldly geopolitical. There was the other moral dimension of the war, in the sense that liberal democracy was a more moral system than communism, and therefore we were also engaged in a moral system. And I think that was true about liberal democracy being more moral. But I don’t think it was a fundamental thing that drove the United States where it went.

Kasparov: We’ll be right back.

[Break]

Kasparov: You have written about Trump’s diplomatic model. And you seem to find some coherence in what, to me and many others, is a very incoherent set of events. Can you explain the pattern you are witnessing and describing in that analysis?

Friedman: First, understand what he sees. Since 80 years, the United States has been continually involved in warfare with essentially communism, in a certain way, but also in wars such as in Afghanistan. A war such as in Vietnam; it was a moral war. It was against the communist regime, but it was unwinnable. What he came in to do is to say, Look, it’s been 80 years in which a norm has developed of two things. One that the United States is the military force that must be there first and best to combat the Russians. The second was that we have to build an economic system that weakened the Soviet Union and strengthened us. So what I approach these matters with is simultaneously a moral dimension—which is very real and binding people together—and a geopolitical reality, which shifts.

So I see him, at this point, as trying to do the same thing [Franklin D.] Roosevelt did with the banking system in the Depression—issuing executive orders, closing down the banking system and recovering it, restructuring it, and trying to put more people on the Supreme Court because the Supreme Court kept knocking down his rulings. So this is what happens when we have an institutional crisis. And this institutional crisis that we’re having right now is: Do we want to remain as exposed to the world, militarily and economically, as we were? And Trump has come in very openly saying it, but not being believed that this is what he wanted. He asked the question about Ukraine: This is a European war. Why aren’t they fighting it? Why are they looking at us, at what we’ll do? And that’s a very shocking moral thing to do, because the United States is seen as the guarantor of liberal democracy.

And from his point of view, we have paid the price for 80 years of being the guarantor. And so you see a different economic system emerging. The free-trade system emerged out of World War II as part of the Cold War, as a way to strengthen other nations, to some extent at the expense of the United States. Foreign aid emerged as a weapon in the Cold War. And his argument is, Look, the Cold War is over. Russia could not even take Ukraine. How is it gonna take Europe? That’s not the issue any longer. The issue is to restructure the world to see that the 80-year cycle that was created after World War II is obsolete and try to do it.

Now, you do not violate a norm without being considered a tyrant. Roosevelt, interestingly, was called a dictator for doing what he did, which is very similar to what Trump did, which is very similar to what Andrew Jackson and Lincoln did. This happens. But I’m less interested in whether we like or hate Trump. But the way we lived in the last 80 years—and I was in the Army, and my daughter was in the Army fighting in Iraq for what I don’t know, and my son was in the Air Force. And the question was: We were fighting all of these wars, deploying all over the place; do we still need to do that? And the second question comes up: The economic system that was created in order to help us in this Cold War—is it still relevant? Is it still in the American interest?

So what you see happening is where the United States took responsibility for the entire global system, in a sense, for 80 years. It’s not unnatural for it to want to go back to a place where its primary interest is its own interest. So I don’t see Trump as anything but a very obnoxious man personally, and also a man who appears reckless because he’s deconstructing the previous system and opening the door for a new one.

So when I look at the situation here, I see a normal geopolitical shift taking place. The recognition that Russia is no longer a military threat to Europe—and therefore the ability to disengage. This violates all the norms of the last 80 years, but it’s an inevitable process.

Kasparov: I have to give you credit for seeing very early what so many people did not: that Putin’s Russia would become more belligerent and would cross the border, attacking Ukraine. So indeed you even wrote it in your book back in 2008—that not just Russia would attack Ukraine, but also you predicted it would not succeed. So what did you see back then? And just, you know, now could you give us a little bit of insight into the future? So if you are so accurate predicting it, though, I also have to you know, boast, I also made the same prediction. Though more intuitively, not from the same strategic perspectives as you did. But what do you expect to happen now in Russia? What is the end of this war? So just if you combine your analysis of the past, present, and the future.

Friedman: First, why did they have to invade? The northern border of Ukraine is 300 miles from Moscow. The Russians remember Napoleon. The Russians remember Hitler. When the Maidan Square rising happened, the U.S. made a big mistake by involving itself in the future of Ukraine. The Russians took this to mean that they were going to integrate, somehow, Ukraine into its structure. And if I were a Russian leader, and I looked at the map, I would say I can’t live with that. And so I said, the Russians would rationally choose to create a buffer zone between NATO and Russia. But they failed to understand that the border would then be on Poland, so that the Russian army would now be on the border of NATO. And they miscalculated that the United States, which did substantially intervene, would allow that to happen.

Putin has failed. The Russian army has failed. It is not a force to be threatened with. It is now descended to terror bombings in Kyiv. Now the problem is that if the war ends at the current terms, Putin is a dead man. The problem is Putin has no organized opposition. He’s not surrounded by a central committee or a presidium that will look at him and say, You have to go. There’s no way that another leader can emerge, and Putin is fighting for his life. He cannot allow the war to end on the terms it is. It cannot allow the war to cost a million Russian lives, and this is all they have.

For me, the fundamental question is—there are forces inside of Russia that are horrified by this war and what it, how it turned out, and what’s happening now. I don’t know how powerful the oligarchs are. I don’t know how the military is taking it. The military was savaged in this war. I do not understand the internal politics that allows Putin to keep his position.

So in this case, you have to look at the idea of true dictatorship—true fascism, if you want to call it that—where a single person has so destructed opposition forces and will act simply for the purpose of showing that he was not defeated. So I read this as turning out with Putin falling. When? How? I don’t know.

Kasparov: So, Taiwan—it’s another potential hot spot on the global map. It’s hypothetical, but many believe it could be an outcome of the war in Ukraine, that if Putin succeeds even partially, China might be emboldened. But you are quite adamant saying that in recent years the Chinese invasion of Taiwan is unlikely. Why—why so?

Friedman: Well, firstly, you have to ask the question: If this so important, why didn’t they invade 10, 15, 20 years ago? They couldn’t. And they can’t. Now I’ll explain why.

Kasparov: Okay.

Friedman: The problem of invading Taiwan is this: It takes about 15 hours, 20 hours for a landing craft to move from a Chinese port to Taiwan. In that time, U.S. satellites would immediately pick up that they’re crossing the river. In that time, missiles that are loaded on all of these islands that they’re passing through, okay, would possibly destroy those ships. That would be not a difficult thing.

Secondly, if they did manage to land in Taiwan, how would they supply Taiwan—with the ability of the U.S., with drones and everything else that exists now? So the military reality is that the invasion of Taiwan is a much more difficult thing than it appears to be. And this is the reason why, for years and years, they have spoken of Taiwan as part of China but have never attempted a military action. In fact, it was easier to do so 15 years ago than it is now. So this is why they don’t do it.

Kasparov: But just for a moment, just for the sake of this very interesting conversation, imagine that your analysis is wrong, and—it happens to even the best of us—and there is an invasion. How should the United States under President Trump respond? And even more important, how would it respond?

Friedman: I think it would respond savagely. So if they somehow miraculously took Taiwan, we would blockade Taiwan completely. And I suspect, in some way, hammer it to death with drones or even invade. And when I talk about the difference in how I look at the world, I do not ask the question of: What would they do? I ask: What can they do? They have to remember that the United States is one-quarter of the world’s economy. The Chinese grew to what they are now by having access to that economy and simultaneously to investment. So if they went after Taiwan, that would mean some sort of war with the United States. It would mean something worse. Xi [Jinping]’s success in building China into an economic power at vast rates of growth depended on its relationship with the United States. If he cuts those lines, he needs to find alternatives, and there are no substitutions. Therefore, Trump singled [out] the Chinese with extraordinarily absurd tariffs that no one ever expects to be the ones that are there. And demanded a negotiation with China, which the Chinese have hesitated.

But there’s two problems. We have an economic relationship with China and a military relationship with China, and they contradict each other. In other words, we have a hostile military relationship in the Pacific with the Chinese navy; at the same time, an intimate economic defense. So I’ve likened this to the situation of when the Arab oil embargo took place after the 1973 war and left the United States in a very bad economic situation. It was catastrophic.

One of the questions you raised: What if they invade Taiwan? What will the Americans do where we’re in a quasi-military confrontation? This is irrational. What Trump, with his normal subtlety and explanation, has done was: He slammed the door of the Chinese, who now have to make some fundamental decisions. To make them understand that the United States has room to maneuver that China does not have, and try to create a very different relationship with China than exists. In a sense, it is the same strategy as Russia. It’s more likely to work with the Chinese than with the Russians.

Kasparov: Are you saying that Trump has strategy?

Friedman: I’m saying that he’s either the stupidest lucky man in the world or he knows what he is doing.

Kasparov: Okay. So if I understand correctly, it’s very much a reflection of America’s position vis-à-vis Europe during the Cold War.

Friedman: Precisely.

Kasparov: So make sure that our main geopolitical enemy could not get access to the harbors of the Atlantic or Pacific oceans.

Friedman: Yes.

Kasparov: Okay. So just a few words at the end of the conversation about the future. And I think that your vision of the American future is much more hopeful than mine or many others. So the floor is yours to end our talk with this vision of the future that will make us cheer up and sleep better.

Friedman: Well, first we have to remember the United States operates through internal crisis. So every 50 years—for no reason, I don’t know why 50 years—we have a massive crisis. The last one brought into office a president who basically changed the entire tax code. We also have institutional crises. The last time the two crises merged was with Roosevelt. And as we go through these cycles, and we look at the various presidents of various times, the re-engineering of the United States always has first a storm where the norms are being violated—and How can Roosevelt do this, and How can Lincoln do this, and all of these things, okay? And after that there comes a period in which there’s a radical calm that emerges in the country.

So after the Depression and after World War II, Eisenhower emerges and smooths away into the future. So what I see for the future is we are going through the storm before the calm. I was able to predict, I was very lucky—I said the election of 2024 would create the storm. And first we have to deconstruct all the norms, all the systems. And then we go into the period of rebuilding and regenerating. We are very used to getting rid of the norm and replacing it culturally with something new. So that terrific tension that’s within the United States today between the defenders of the ancien régime, if you’ll permit me, and the advocates of the revolution is normal. These happened before, and we had civil wars over them. So we are a very peculiar country. We are a very unique invention, and we build our lives on reinventing things. And so I see the future of the United States as reinventing our relations with the world, reinventing our internal structures, hating the president who did it. It’s a very unpleasant thing when the United States emerges as the superpower in the world to see it going through this performance. And it’s not happy in the United States either. But it’s the storm before the calm.

Kasparov: George, thank you very much for offering us this positive vision of the future. And I admire your belief in America’s ability to self-heal all the wounds inflicted by drastic measures by various presidents. And I hope that your predictions based on historical analysis and patterns will materialize, and America will emerge stronger than ever before. Thank you very much for joining us.

Friedman: And thank you for having me. And remember—we survived the Civil War.

[Music]

Kasparov: But it was a civil war first, so—yes? (Laughs.)

Friedman: First. Yes.

Kasparov: This episode of Autocracy in America was produced by Arlene Arevalo. Our editor is Dave Shaw. Original music and mix by Rob Smierciak. Fact-checking by Ena Alvarado. Special thanks to Polina Kasparova and Mig Greengard. Claudine Ebeid is the executive producer of Atlantic audio. Andrea Valdez is our managing editor.

Next time on Autocracy in America:

Mathias Döpfner: I think it’s a very nice but slightly naive idea: that now the big historic opportunity is since America is sending a lot of disturbing and surprising signals, Europe could do it alone or could do it better. It’s not going to work. The challenges of China, the challenges of Russia are much too big in order to be solved by Europe alone. And I would even go that far—they are also way too big than being solvable by the United States alone.

Kasparov: I’m Garry Kasparov. See you back here next week.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

Illustration by Akshita Chandra / The Atlantic.*

Illustration by Akshita Chandra / The Atlantic.*

Image via VGHF.

Image via VGHF. Image via VGHF.

Image via VGHF. Image via VGHF.

Image via VGHF.

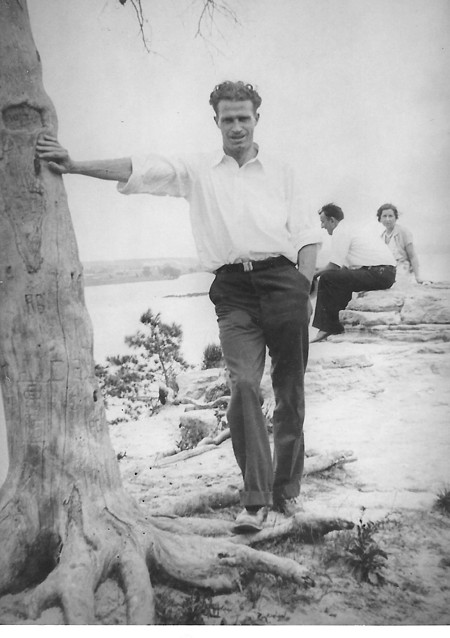

Hermann Walecki, who founded Westwood Music, circa 1934 (Courtesy of Nancy Walecki)

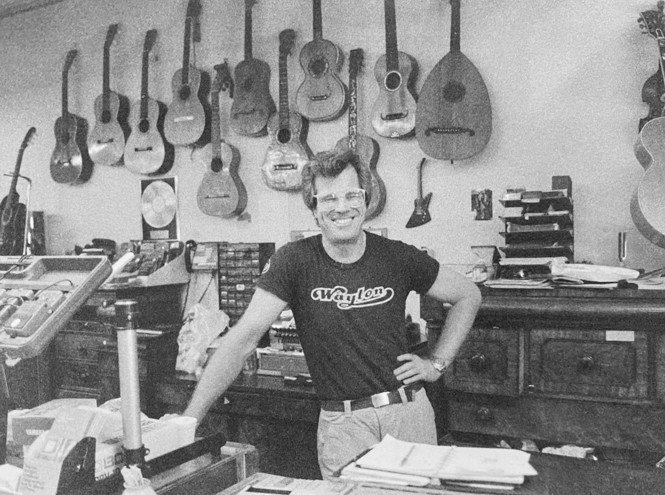

Hermann Walecki, who founded Westwood Music, circa 1934 (Courtesy of Nancy Walecki) Dad, in Levi’s and a Waylon Jennings T-shirt, behind the counter of Westwood Music (Courtesy of Nancy Walecki)

Dad, in Levi’s and a Waylon Jennings T-shirt, behind the counter of Westwood Music (Courtesy of Nancy Walecki) The Eagles. Don Felder is in the Westwood Music T-shirt. (Published in the Sydney Morning Herald)

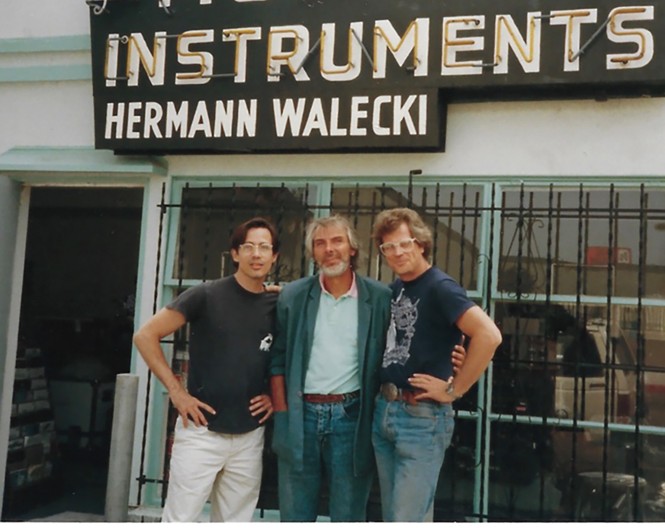

The Eagles. Don Felder is in the Westwood Music T-shirt. (Published in the Sydney Morning Herald) Jackson Browne, Glyn Johns, and Dad outside the store (Courtesy of Nancy Walecki)

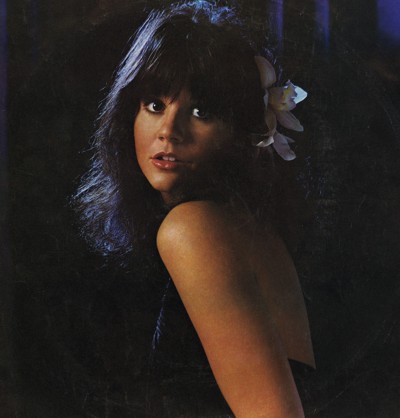

Jackson Browne, Glyn Johns, and Dad outside the store (Courtesy of Nancy Walecki) A publicity photo for Linda Ronstadt’s album Simple Dreams. Sunburn courtesy of Dad. (Alamy)

A publicity photo for Linda Ronstadt’s album Simple Dreams. Sunburn courtesy of Dad. (Alamy) Freddy and the Fishsticks on the road, 1981 (Courtesy of Nancy Walecki)

Freddy and the Fishsticks on the road, 1981 (Courtesy of Nancy Walecki) A photo I took at the Newport Folk Festival in 2022, right before Joni Mitchell took the stage. Dad is holding Green Peace, the guitar he made for her. (Courtesy of Nancy Walecki)

A photo I took at the Newport Folk Festival in 2022, right before Joni Mitchell took the stage. Dad is holding Green Peace, the guitar he made for her. (Courtesy of Nancy Walecki)